On the fifth anniversary of her death, my mother shared memories of her with me around a Thanksgiving turkey dinner. I wanted to know more about her and where I came from. My search stretched into late nights for weeks. I uncovered much of my family tree through materials like annual censuses, newspaper obituaries, birth certificates, and death records from the Public Archives of Nova Scotia.

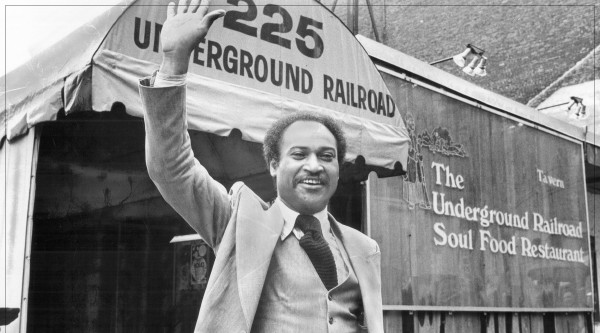

It was easy to trace my white maternal side. The wedding photo above is of Rebecca Giles and Andrew Macdonald, my 3rd great-grandparents. Giles was born in 1872 and died in 1965. In fact, the line could be followed back to when they first arrived on the shores of Nova Scotia in the 1700s, and beyond that, to Scotland, Germany, and France. But figuring out my mother’s Black paternal side was much harder. I don’t have much information about him, and of what I do know, there isn’t a great trail of records to follow.

It was easy to trace my white maternal side. The wedding photo above is of Rebecca Giles and Andrew Macdonald, my 3rd great-grandparents. Giles was born in 1872 and died in 1965. In fact, the line could be followed back to when they first arrived on the shores of Nova Scotia in the 1700s, and beyond that, to Scotland, Germany, and France. But figuring out my mother’s Black paternal side was much harder. I don’t have much information about him, and of what I do know, there isn’t a great trail of records to follow.

This speaks to a broader issue around the disdain for Black life in Canada, which translates to a lack of records and documentation of Black life, and of Black people who collect and handle these records.

Those people are called archivists. Archivists acquire, manage, process, store and disseminate information– this could look like textual material, pictures, maps, architectural documents, sound recordings, and more. But in Canada, not many of them are Black. According to the 2021 census from Statistics Canada, there are 20 working archivists in Canada who identify as Black. That’s less than 1% of the total number of working archivists in the country.

That’s a problem. More Black archivists are needed because they take on the complex and delicate mission of caring for our histories and ensuring we're represented accurately, not through the distortion of the white gaze, which often slots us into anti-Black caricatures.

Black communities recognize this importance and are creating their own interventions. Melissa J. Nelson, Toronto-born and of Jamaican descent, works at the Archives of Ontario. While enrolled in her master's, she says she was often the only Black person in most of her archive classes. After graduating, she kept wondering, where are all the Black people?

{https://www.instagram.com/p/C20ubpBNUcy/?img_index=1}

“I started to be intentional about networking with people,” says Nelson. Eventually, she decided to create her podcast Archives & Things to document the conversations she had with archivists and make the insight revealed in them available to the public. Seeing a need for more connection between Black archivists, memory workers and researchers, Nelson also established the Black Memory Collective. The collective held its first virtual social event on February 3 for its members. Black people working in different industries– from artisans to professors to artists in theatre and fashion design– joined the call. The next virtual event will be on March 2.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/C0acps2Nt0C/}

“I realized there's a real need to connect with each other because a lot of us feel alone,” says Nelson. “There's so much more that we can accomplish when we're not working in isolation.”

And there's lots of work to be done. Much of Black life is absent in the archives, as documentation is often slotted into categories of Black excellence or enslavement, according to Nelson, and ordinary Black life is often neglected.

“The collective will encourage more Black people to come into this field or at least do archival work,” says Nelson. “It'll really reshape the way we see the past, and the way that we see ourselves, but also the way we see our futures.”

It’s a movement that has gained momentum in Canada over the past few years. Cheryl Thompson, an associate professor in Performance at The Creative School and the director of the Black Creative Lab, is a pillar of this movement. She’s written a ton of scholarship around inequity in the archives, including Black Canada and why the archival logic of memory needs reform, published in 2019, where she states that “the very structure of the archive erases from public memory the lived experiences of Black Canadians.” Thompson is also the director and creative lead of Mapping Ontario’s Black Archives, a brand which works to provide the first comprehensive inventory of Black Ontarian archival collections.

"There are a few things that make MOBA unique,” says Thompson. “It's one of the first platforms with a comprehensive database of Black archives that will eventually have the ability to function as a searchable archive for digital assets in Ontario, and we are currently expanding that reach across the country.”

The website also has tips about where and how to start your research, as well as the best way to go about what is sometimes a very daunting process.“MOBA creates conversation and connection with the Black community but also the wider community who might not be familiar with Black archives,” says Thompson.

At the University of British Columbia's School of Information, is assistant professor Elizabeth Shaffer, whose scholarly work explores the intersections of Blackness and archives, with particular attention to race, gender and digital infrastructures. She sees education as a tool for change.

Shaffer hopes to introduce a research programme that centers Black liberation and Black feminist theory in the context of the archives. She teaches her students archival theory, history and practice, while also challenging them to critically engage with what they’re learning. She encourages them to bring their “whole selves” to the content, establishing ethics of care in archival and mending the violent erasure it often reproduces.

“I'm optimistic enough to think we can change it,” says Shaffer. “I think it's a lot of heavy lifting. We need more [Black] archivists in the profession. But we also need folks who work from within the profession to shift how we think about memory and what is included in the archives, not just to seek out stories and include them into systems that are inherently racist. [But] if we don't have more Black archivists, or memory workers, then I think we're not going to see that change that we want to see.”

Don’t shy away from the archives. You never know what you might find– and it’s very important that someone is looking.

By

By