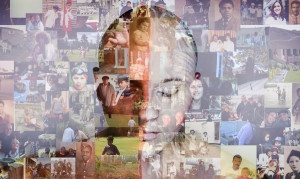

Part of the festival's short film category, Environmental Racism and Resistance is HEALING OUR COMMUNITY: BLACK CREEK COMMUNITY FARMS, narrated by the Director of the farm Leticia Deawu. I had the delight of sitting with Leticia, who affectionately goes by her Ghanian name Alma, which she informs me means “Saturday born” to discuss her work at the farm and the film.

Leticia Alma Deawu, has not only been the Director at Black Creek Community Farm for the past eight years, but is also the Chair of Seed Change (formerly USC Canada international) which works with farms in 11 countries, and sits on the board of the Jane & Finch Action Against Poverty.

Alma shares the origins of Black Creek Community Farms is quite different from what the organization has evolved into now. In 2013 the farm was managed by another organization and its main focus was to grow produce for sale at Evergreen Brick Works’ Farmers Market. There was a purposeful shift to focus its effort on the immediate community and address issues concerning food insecurity in the Jane & Finch/ Black Creek area. “The community faces multiple systemic barriers, however, despite the hardships, it is vibrant, resilient and engaged.”

Jane & Finch is the community Alma grew up in, still resides, works in and now raises her own family. When discussing the transformation of BCCF, Alma shares there are a few key things they had to consider. “How can we embed the work within our community, ensuring the community members are not just on the front lines but represented on our board, management and in decision making positions. It has been a long road to get to where we are and we have a long road ahead of us. There is no farm like BCCF and there is no blueprint for us to follow, we continue to evolve and shift to meet the needs of our community.”

Despite being one of a kind in Ontario, possibly even in Canada, and growing organically without a guide, what Alma and her team have created has caught the attention of many other organizations around the world. In the film we see other organizers from Japan to Brazil coming to visit the farm, seeking advice on how to create a movement like BCCF in their own communities.

The timing for this film is impeccable, as it tackles many issues finally being discussed in the mainstream, such as diversity, inclusion, representation, and equity. Conversations around ensuring those that occupy board seats reflect the people served by a company/organization as well as discussions regarding poverty and sustainability all make an appearance in Healing Our Community. The ramifications of the global pandemic can be seen right across the country exposing the fragility of our social safety nets.

“If you look at the research that Food Share has pulled together which really speaks to what we already know, Black people are 3.5x more likely to face food insecurity, when we look at the numbers within indigenous communities those numbers are even greater. For a country like Canada that is unacceptable,” says Alma. Pre COVID 4.4M Canadians faced food insecurity, now the number has ballooned to over 6M. “If we were to look at the race of those individuals we will see that they are predominantly Black, Indigenous and racialized people. “Even when we look at where COVID hit (hardest) in the city; we know this has roots in colonization and systemic racism hence why people are facing all these challenges.”

The Jane & Finch area is home to over 100 temporary job agencies, consequently, the majority of jobs held by the residents are precarious. Food insecurity is tied to income and job security. Additionally, Jane & Finch has one of the highest eviction rates in the city of Toronto according to a study done by The National Post. Gentrification is a huge issue as well, as people are being pushed out of the community to make space for more affluent residents. “Great, we have four new subway stops but at what cost,” says Alma.

“When are our Black and Indigenous people going to get their fair share? They are working two and three jobs to make ends meet. When I speak to some of the Aunties in the community they are often forced to choose between paying rent, paying for medication or buying healthy food. For people that have worked 30 years in this country to have no pension, they retire basically with nothing.”

In the film a key piece of information is shared, Black and racialized communities pay seven percent more for the same fresh vegetables as other neighbourhoods.

Food sovereignty is a crucial matter in the Canadian context. This film begins to explore the impact of urban agriculture and how it affects an entire community. “It’s not just the rich Martha Stewart-like lady with the pearls doing gardening in her backyard, but this can be something that is healing; especially for Black people whose ancestors come through the North American slave trade. Our ancestors were brought here because of their joy of working the land and that was exploited. There is a lot of trauma for many of us when we are being told to go back to the land. We want to showcase how farming can be healing to a community and bring groups of people together.”

By

By