On November 12 2013, the Ontario Court of Appeal struck down this part of the law, saying it creates a grossly disproportionate sentence, amounts to cruel and unusual punishment and is therefore unconstitutional. It was the first appeal court in Canada to do so.

The Crown challenged this decision and the case has now gone all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

This Supreme Court case is important because it will decide whether that law is unconstitutional on the grounds that it violates people's rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

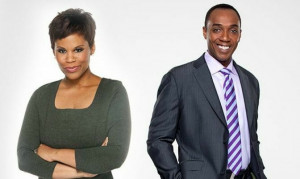

Anthony Morgan, African Canadian Legal Clinic policy research lawyer, and Faisal Mirza, African Canadian Legal Clinic co-counsel led the Supreme Court arguments on November 7 2014.

The African Canadian Legal Clinic argues that the law is unconstitutional because it can too easily result in African Canadians receiving jail sentences that are much longer than the sentences they actually deserve. This is a hypothetical scenario that the ACLC put before the Supreme Court to show how this law can result in an African Canadian receiving a significantly unfair jail sentence of 3 years for this crime:

An 18 year old African Canadian youth works part-time as a Community Youth Worker at a community centre in Toronto, Ontario. He is a first year university student who attends York University. He has no criminal record. He has a number of acquaintances that he grew up with that are linked to gangs and whom he regularly comes into contact with by virtue of living, working and going to school in a lower income community. His family cannot afford to live elsewhere.

One evening, while walking to his vehicle to drive to the community centre, an acquaintance of his, who is also a user of the community centre, asks him for a ride there. While en route to the community centre and inside the car, the acquaintance shows he has a loaded prohibited or restricted firearm. To bide extra time to think about how to avoid bringing the acquaintance to the community centre, he tells the acquaintance that he wants to get something to eat first. The acquaintance agrees to this and they take a short detour in the direction of a nearby McDonald's. Before arriving at the McDonald's, the police pull over the vehicle. During their investigation, they locate the firearm underneath the passenger seat. The young man and the acquaintance are both charged and prosecuted with possession of a restricted firearm. Both men are later convicted. The trial judge concludes the young man's knowledge and control was brief and his conduct otherwise mitigating.

The African Canadian Legal Clinic argued that while the driver (who has no criminal record) should be punished in some way, he is not as guilty as his acquaintance who actually brought the loaded gun in the car. The problem with the current law (mentioned above) is that it treats the driver's actions as if they are just as bad as the passenger's actions. The law does this by requiring both of the young men to receive a minimum of three years in jail for possession of a loaded firearm.

The African Canadian Legal Clinic argued that giving the driver the same minimum three year jail sentence as the acquaintance in the above circumstances would amount to cruel and unusual punishment or treatment of the driver because the sentence is much higher than what he should receive when you consider the full context in which he was found with the gun.

“When you look at the hypothetical scenario above, you see that it's a situation that could happen to a significant number of African Canadians because we are considerably overrepresented in communities where there are elevated rates of unemployment, poverty, public housing occupancy, dependence on social assistance. Guns are more likely to be present in such communities, meaning Blacks are more likely to be charged with this offence. A law requiring a mandatory minimum sentence robs judges of the ability to consider these factors to craft an appropriate sentence for the individual who gets caught up in this offence,” says Morgan.

This case is also important because it is the first time that the Supreme Court will be given an opportunity to address the over-representation of Blacks in Canadian prisons. Despite representing only 2.9% of the Canadian population, African Canadians make up 9.5% of Canada's prison population. The rate of Black incarceration has also gone into hyper-acceleration over the past 10 years. A government agency has reported that, as a subgroup, Black inmates have increased every year, growing by nearly 90% over the last 10 years. Meantime, Caucasian inmates actually declined by 3% over this same period.

The ACLC used these facts to argue that the abovementioned law should be struck down as unconstitutional because it contributes to the trend of filling up Canadian prisons with Black bodies.

There is a very strong consensus among academics and policy makers that mandatory minimums and tougher jail sentences in general do not reduce violent crime. “They simply don't work. They have only been effective in increasing the number of Black people in prison and extending their stay when they are there. But all the while, the rates of violent crime have remained steady or even increased in some instances,” says Morgan.

Critics of the appeal argue the ACLC’s efforts are misplaced. Other lawmakers argue that anyone found with a gun deserves to go to jail and that if this minimum sentence law is more likely to affect African Canadians then the focus should be on ridding the Black community of guns, not on the laws that punish them.

“It's not enough to look at the individual in a narrow sense of who has been found with a gun. We argued that the court has to look at the larger socio-economic conditions that make it so easy to access a gun in the first place. When you look at the larger conditions, then you realize that there are many people who will be caught in this offence who aren't as morally blameworthy as the gang-affiliated drug traffickers we've all been taught to think of, as the only person who might be found in possession of a gun in these communities. But the precise problem with this mandatory minimum law is that it leaves judges in a position where they have to say, it does not matter why guns are so prevalent in Black communities, all that matters is that this first time offender was found in possession of a gun, so they get a mandatory minimum of 3 years in jail. The ACLC argues that that is deeply unfair because to craft an appropriate sentence, judges have to be able to look at people in the full context of their life experiences, background and socio-economic location,” says Morgan.

Morgan admits that the ACLC recognizes that some first time offenders found in possession of a gun should most certainly go to jail in certain circumstances. But argue each case should be judge individually and a judge should be able to determine how long each individual should go to jail, instead of having a law that is just a blanket three year mandatory minimum.

“In principle, the law treats the social worker who takes a gun from one of their youth to prevent a shooting, the same way as it treats a corner boy who has dropped out of school, sells drugs, carries a gun all the time and is more than willing to use it if they have to. Maybe the social worker exercised terrible judgment by not bringing the gun to the police right away, but should they get an automatic minimum of three years in jail for that? Surely judges should be able to impose a less severe sentence. Under the current law, they simply can't. So the social worker ends up in the cell next to the gun-toting drug dealer, both of them there together for at least three years,” says Morgan.

Morgan concedes this is an extreme example, and he has never come across such a case, but believes it could very well happen based on how the current law operates.

The case has reached its final stage at the Supreme Court of Canada, when it was argued on Nov 7, 2014. The main parties, delivered their arguments on whether this law results in cruel and unusual punishment and is therefore unconstitutional. Now, the SCC will deliberate on the arguments and will come out with a decision around late April or June 2015.

By

By