Indigenous and African diasporic peoples exchanged in trade of goods, cultures, and customs. We know this from the archeological record that can connect Egypt and other parts of the African continent to South America, and North America.

We need to know and understand our history, from our perspective and not from a limited white-settler perspective,” says Ciann Wilson, Assistant Professor in Community Psychology at Wilfrid Laurier University and Principal Investigator for the Proclaiming Our Roots project.

“When we leave our education of ourselves and our past to the deeply entrenched lies and revisionist history colonists tell and re-tell, we are bound to the limits of their version of our humanity and our possible futures,” says Ciann.

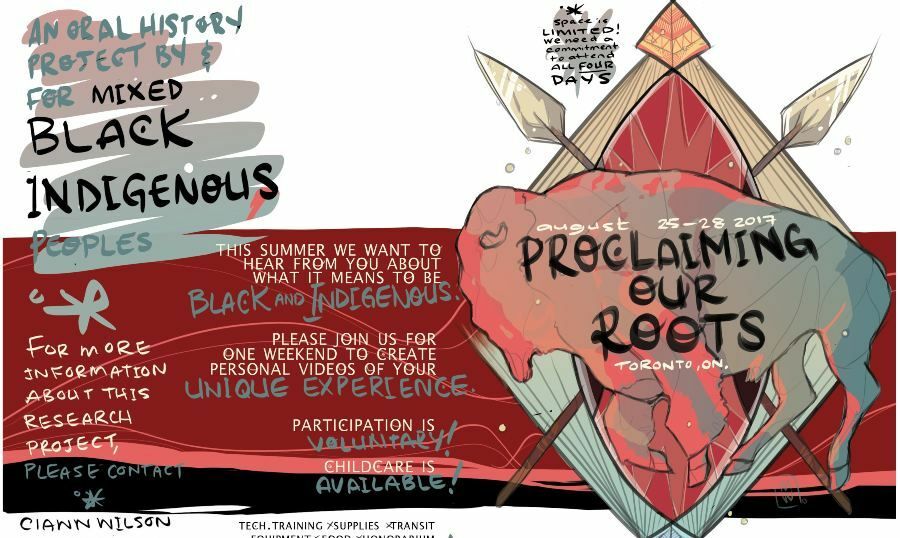

The Proclaiming Our Roots project is intended to include the history of mixed Indigenous and Black people into the larger dialogue of Indigenous history and contemporary reality in the Canadian nation-state. Two of the project leads, Ciann Wilson and Denise Baldwin, had many conversations about the relationship between, and similarities of Black and Indigenous communities before joining forces for this project.

Denise Baldwin, who is a Black-Anishinaabe Kwe citizen from the Chippewa's of Nawash First Nation in Ontario knew that the conversation about Black-Indigenous people deserved a public platform in national discourse in Canada. Having both worked in support of Black and Indigenous communities for over twenty years combined, Denise and Ciann identified a pattern of the silencing and lack of acknowledgment of Black-Indigenous Canadian history.

"The inspiration for this project was Indigenous-Black people not having a place in the larger Canadian consciousness and national dialogue of indigeneity in Canada. We wanted to create that space, and we wanted to use arts-based processes to engage folks and use artspace approaches to do the work," says Ciann.

The Proclaiming Our Roots project is a digital oral history archive that creates space for personal video stories which depict the stories of Canadian Black-Indigenous people and their history. The participants are from all over Canada, with diverse Indigenous (i.e. First Nations, Inuit, and Metis) and African-diasporic (i.e. continental African, Caribbean, and Black-Canadian) backgrounds and identities.

Denise Baldwin also created a digital story for the project. In her digital story, Denise recounts her family history as a story to her son, sharing that she is the youngest of nine children, born just outside of a reserve in Ontario. Denise says she lived most of her life in a small white town. Her parents met and married in 1957 in Toronto. Denise’s mom is Indigenous, and of Metis ancestry and left the reserve when she was ten years old. Denise’s’ father lived on his own in Toronto from the age of fourteen. Denise’s father is a fifth-generation Black Canadian, with roots from the United States and the continent of Africa. Denise’s great-grandparents escaped slavery in the U.S. and found refuge on Canadian soil.

Ciann notes that “We (people Indigenous to North America, and/or Africa) have always been telling our stories through the arts. Now we are using the technology available to us, to do what we have always done. Culture evolves and adapts, and what is innate to us will always find a place in our society. Our ability to adapt, while still holding onto the stories of our past, the stories that make us who we are, is integral to how we have managed to survive despite all of the attempts to exterminate us through colonial violence.”

The impact of the program has been transformative for many of the participants, as well as the community. "One participant could not read very well as the Canadian educational system had failed him as it is riddled with racism, marginalization, and oppression for Black and Brown students. The participant had not completed high school, but since participating in the Proclaiming Our Roots project, he was encouraged to go back to school and complete his high school education. Another participant is in the planning stages of founding the first Indigenous-Black reserve in Canada. He can trace his roots back thousands of years. There are these are policy-level changes and shifts happening as the after-effect implications as a result of the will of the people who took part in the Proclaiming Our Roots projects,” says Ciann.

Another topic the project addresses is the definition of Indigenous. The project is aimed at honouring the histories, realities, stories, and experiences of people who are of African diasporic and Indigenous ancestry, and who reside on Turtle Island.

"Some Indigenous people define Turtle Island to include North America, the Caribbean, and Mexico and that is what Proclaiming Our Roots aligns with. Some people only consider North America as Turtle Island. In Canada, there are over five hundred Indigenous nations and fifty-three Indigenous languages. The spectrum of self-identified Indigenous people is vast, but there is intentional differentiation between Indigenous people from the North versus the South, and that is a notion that needs to be unpacked.”

Ciann said she considered the North-South distinction to be geopolitical, which creates another avenue to exclude some Indigenous people over others. "The terminology has deep historical and cultural roots and opposes and challenges narrow definitions of Indigeneity," says Ciann.

“While we are talking about truth and reconciliation for Indigenous people, we have to ask where is the place of Indigenous-Black people, who have a complex history that has been predominantly erased due to anti-black racism that is so prevalent in Canadian society?” asks Ciann.

The next step for the Proclaiming Our Roots project is securing funding for their phase two program. This phase will consist of supporting participants to learn the methodology of creating digital stories so they can carry on the practice within their communities. "It’s a train-the-trainer model that two of the amazing Indigenous-Black Ph.D. students I work with, Ann Marie Beals and Kayla Webber, thought of. We want to facilitate learning the approach of digital storytelling, so the participants are empowered with new transferable skills. Whether we can continue to receive funding or not, people can continue this important work for their self-identities, communities, and upcoming future generations," says Ciann.

Click here to check out more of the project's digital stories.

By

By