In Canada, all citizens are free to find work and access the welfare state set up on their behalf, yet for migrant labourers, those same rights are not guaranteed.

Migrant labour in Canada makes up a dramatic portion of our agricultural economy. In Ontario, migrant workers are 41.6% of the labour force. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, over 20,000 people accounted for the seasonal agricultural workforce in Ontario alone.

As the 12th largest agricultural producer globally, Canada's population ranks only 38th globally, meaning the labour of migrants from Mexico & the Caribbean make an integral part of our economy.

Brought to this country to work the menial agricultural labour we Canadians avoid, migrant labourers are treated unjustly. According to a new class action lawsuit, migrant labourers are being systematically mistreated.

The class action claims migrant workers, mainly from Jamaica and Mexico, have been systematically discriminated against, and are seeking half a billion dollars in compensation as reconciliation to migrant workers who were forced to pay into Canada’s employment insurance scheme, without being able to use it themselves.

The class action says that while nothing in the law forbids migrants from accessing EI, it has been made impossible for them.

“The fact that migrants pay into EI but do not get anything out, goes against the Charter of Rights and Freedoms,” said Louis Century, a Toronto-based lawyer involved in filing the class action by Goldblatt Partners, in conjunction with Koskie Minsky and Martinez Law. “Because of tied employment, the moment of job loss makes the worker ineligible for EI, because under the EI scheme, you need to be both ready and available to work to get EI benefits.”

In other words, migrant workers cannot access EI since their employment is seasonal, they usually return home once the crop season is over, so they technically are not “ready and available” for work.

According to Century, the class action lawsuit is fighting an institutional form of work known as tied employment. Tied employment conditions migrant workers' visas on their employer. So whenever the employer decides to end the employment, all EI payments are nulled. Tying workers to their employers is an institutional form of servitude thousands of years old. Human rights advocates all over the world are looking at Canada, five hundred years from the beginning of the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade, and wondering whether the system of forced work really ended, or just changed.

How Tied Employment Turns Into Systemic Slavery

Forms of slavery change over time, what is important to keep in mind is how much freedom someone has to affect change in their own life. The major claim in the class action is that Canada’s whole approach to migrant labour turns Canada into a labour prison.

The Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SAWP) is a Canadian government program that allows Canadian farm employers to hire temporary workers from Mexico and Caribbean countries when local workers are unavailable to fulfill labour demands. Under the SAWP, workers can stay and work in Canada for a maximum of 8 months between January 1st and December 15th of each year. The SAWP applies only to temporary foreign workers who are citizens of Mexico and specific Caribbean countries.

Inaugurated in 1966 the SAWP program was racked with issues of racism and bondage from its outset. One letter, penned in 1962 from the Deputy Minister of Citizenship and Immigration George F. Davidson, railed furiously against the possibility of a foreign workers program between Canada and Jamaica:

“This is not immigration, but rather the importation of contract labour gangs on a sort of indenture basis.” Davidson was responding to a letter from a professor at UofT asking about the possibility of a foreign workers program with Jamaica, comparable to one signed between Jamaica and the US. He would be overruled by 1996 when the SAWP system was inaugurated. And the experience of migrants has proved Davidson sadly correct.

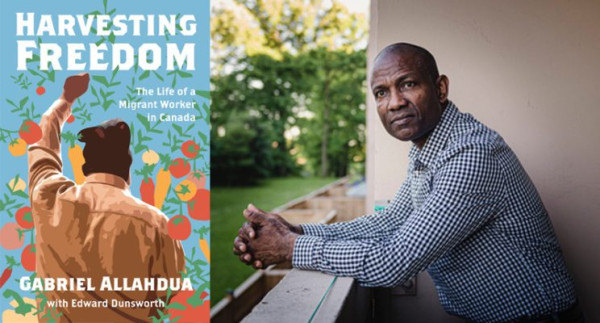

Last year I wrote a piece on the book Harvesting Freedom by Gabriel Allahdua. The book explores Mr. Allahdua’s journey from a farmer in Saint Lucia, and a migrant worker in Ontario, into an advocate in Toronto. When speaking on his time in the agricultural sector, Mr.Allahdua notes how labourers had “no overtime, no maximum hours, and no breaks.” Like a labour gang, Mr.Allahdua and his co-workers often worked hours they were not paid for. While workers under the SAWP are eligible for certain benefits, such as the Canada Pension Plan, and are subject to income tax laws, garnering those benefits is impossible. Gabriel Allahdua found this out when he attempted to move from the SAWP into permanent residency status, a rare occurrence already.

“While I had to stay in Canada for my immigration interview, I was not allowed to work for the first nine months after my SAWP contract, nor could I pull from the employment insurance I paid into,” said Allahdua. Not only was he banned from accessing his own money, or working for anybody, but his health insurance ended the day his contract did. “I could only apply for a new health card after my immigration application had been approved.” For nine months, between his status as a farmworker and his permanent residency application, Allahdua had no right to access resources, work or move.

The denial of these freedoms to those living in Canada is a human rights issue. Tomoya Obokata, UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, in a statement at the end of a 14-day visit to Canada, railed against SAWP and similar programs for making migrant workers "vulnerable to contemporary forms of slavery, as they cannot report abuses without fear of deportation.” What else can you call the sort of situation that leaves you without money, work or movement?

How To Instill The Freedom

If SAWP is so racist and evil, should we cancel the program altogether? Chris Ramsaroop, a representative of the volunteer-run political collective Justice For Migrant Workers (J4MW), says no. In his eyes, and the eyes of many migrants, the program works for struggling people in the Global South.

“Workers are paying into the system and not receiving benefits.” Ramsaroop, who teaches Caribbean Studies at the University of Toronto, has been fighting for migrants in Canada for years. “We're not calling for the abolition of workers paying into the EI system. What we're trying to say is workers should be getting EI access when they return to their home country.”

Through his work with J4MW, Ramsaroop was able to ask them directly what changes they wished to see to their precarious working conditions. The migrants he interviewed, simply said “EI & immigration papers.”

They want to earn money, be paid correctly for their labour and have a real chance to make a new life in Canada. While Canada wants the labour of Black and Brown folk, they never intended to provide avenues to permanent residency to nonwhites.

“They (Feds) were concerned about interracial relations between black men and white women, about migrant workers getting access to EI benefits and other forms of entitlement that they would believe would make them Canadian,” explains Ramsaroop.

Currently, the case is up for approval to be tried as a class action. “One of the things the court is going to look at is if it's appropriate to lump all of these class members together in litigating this,” explains Century. His team must prove that the program affects Black and Brown people as a social class. And while the government itself has admitted the migration system is racist to Black people especially, Louis says political conversation avoids talking about racism, preferring to stick to issues of tied employment. But without the context of racism and the history of slavery on the continent, the suffering of migrants is severely blunted. Moving forward we need to make sure both race, class and status are part of the narrative surrounding Canada’s new class action. Beyond that, Ramsaroop says people need to speak up and organize around migrants if they ever want a chance at freedom.

By

By