“I am not the spokesman for the Negro; that honour has not been given to me. Do not let me ever give anyone that impression. However, I want the record to show that I accept the responsibility of speaking for him and all others in this great nation who feel that they are the subjects of discrimination because of race, creed or colour,” he said.

According to Black Vote Canada, only three Black people in Canada ever held office before Alexander; Abraham Doras Shadd (Raleigh, Ontario city council, 1859) Leonard Austin Braithwaite (Ontario MPP, 1963) and Firmin Monestime (mayor of Mattawa, 1964). That’s about 1 Black elected official every 25 years.

To date, there have been at least 126 Black elected officials in Canada, representing various parties and at all levels of government but it’s still well below proportional representation given Canada’s roughly 1.5 million Black population.

Last August, 45 Black politicians (MPs, provincial leaders, senators, city councillors and school trustees) gathered for two days of “historic” meetings in Ottawa with the explicit objective of building consensus and proposing solutions to improve Black Canadians’ lives. The group, known as the Canadian Congress of Black Politicians, signed a values statement outlining their goals and they committed to continuing to meet regularly to ensure progression towards their collective mission.

Hearing about this meeting, I wondered what the politicians discussed and how it felt to be in the presence of such a large cohort of fellow Black politicians. It also made me wonder about their experiences as Black politicians, why they wanted to get into politics, how they deal with racism, and what their relationship with other Black politicians is like.

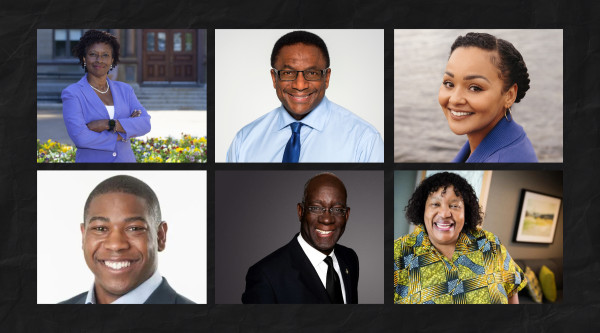

Last October, I contacted dozens of Black Canadian politicians, in the end, I spoke to 13 of them about their experiences, and a few of them said our conversations were therapeutic. Those conversations make up our new three-part series "Black On The Hill".

One thing I learned is that whether it’s the symbolic power of representation that inspires others or bringing invaluable lived experience and perspective to political discussions and influencing decision-making, it’s clear that the contributions of Black Canadians are vital to Canadian politics.

Last August’s meeting was the culmination of years of work led by Tony Ince and Michael Coteau. When the two first met, Tony brought him a book called Black Ice, about the Maritimes' Coloured Hockey League, which Coteau knew little about. The exchange encapsulated what the two set out to do, share and learn about the varied experiences of Black Canadians and reflect on their own experiences. Matthew Green joined the fold a few years later, and the three men were at the heart of the historic meeting.

Interviews were conducted separately and have been slightly edited for length and clarity.

BB: Why was it important for you to establish connections with other Black politicians?

Michael Coteau (Ontario Liberal MPP for Don Valley East 2011-2021/Liberal MP for Don Valley East since 2021): We had so many similarities but no connection to each other. So, we established a very ad hoc organization called the Congress of Parliamentarians in 2015 and the aim was to bring people together. I believe we had 14 but it was a very limited group of people considering there weren't many Black politicians in the country.

Tony and I decided we had to keep this going and we invited Matthew Green when he was a city councillor in 2016 and the three of us chaired a meeting and we decided after years of talking about it that we’re going to invite all levels of government. One of the things we discussed, which was really important was the name, that the Congress of Black Parliamentarians should really become the Congress of Black Politicians.

Tony Ince (Liberal MLA for Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia since 2013): We need to all come together because regardless of what party you're with or where you're representing, the first thing that I would say to any of us is, you can be partisan or not but our group has to be non-partisan because no matter where we go, the first thing that identifies us is our skin colour. So, if we can come to a table and share challenges, different perspectives from different communities across the country, I think we could better represent those people and to try to get more engagement, because our communities are not very engaged in the political process.

Matthew Green (Hamilton City Councillor 2014-2018/NDP MP for Hamillton Centre since 2019): Over the years there's been attempts for us to meet and convene in these ways, we often do it informally, via social media, at events, you know the little things where you're in the room and there's only a handful of us and you have “the nod”, you have the acknowledgement that the person that's in that room with you likely has similar stories or at least some kind of shared perspectives and common ground. Now, we also acknowledge that the Black community is extremely diverse, that no one party or political viewpoint necessarily encapsulates all of the Black perspective, which is why having a non-partisan setting through multiple levels of government from coast to coast to coast provided us the challenge of finding common ground despite our political difference but around our shared experiences.

{https://twitter.com/KamalKheraLib/status/1754850359388881001}

BB: What did it feel like to be in the presence of all these other Black politicians?

Michael Coteau: It's been a long time coming. There hasn't been enough capacity to have a group of politicians come together like this because we just didn't have a lot of representation. The Wynne government in 2014 having three members was a big deal, and the NDP in 2018 having five members was a big deal, provincially. The Trudeau Government having several members was a big deal. Traditionally, those governments had a single representative for a long time. So, I think we've hit a capacity that enabled us to have that meeting in a meaningful way, from a numbers perspective. The significance and the historical piece to it is quite extraordinary.

The incredible thing is everyone was saying the same thing. It was about how we tackle systemic racism and anti-Black racism. How do we create opportunities for young people, how do we look at ways to strengthen education systems, how do we encourage more people to get involved in politics, it was universal. The premise that Tony and I have always worked from to get to this point was that there's too little of us to argue or to fight each other. Our numbers are not good, they're not reflective of our percentage. Our point was always “Let's work together and find at least common ground and build from that.” We don't have to agree on everything, we have different perspectives on the role of government from an ideological perspective, on fiscal policy and issues, around justice; there are so many differences but there are things we just agree on. Everyone agrees that racism is real, everyone agrees that anti-Black racism is real and government can be used as a tool to tackle some of those issues.

Tony Ince: When we discussed one of our pillars, which was trying to look at the word racism and how we frame it, I and several others were firmly entrenched in the belief that we have to highlight it as anti-Black racism. There were a few other individuals who were really uncomfortable with that because of the dynamics of their communities, and how they might perceive it as creating a divide because of that term.

I highlighted that that hasn't been an issue for me and my community because as the Minister when I championed the issues of the African Nova Scotian community, I was still representing everybody else in my community; but that's my community. I'm sure the dynamics are a little different in Quebec or out West. So, we had a very deep and lengthy conversation about that and the fact that we often have to hold back when it comes to racism and have to go with the status quo, where we're just talking about racism which includes everybody, which ultimately puts us on a lower rung or puts us for lack of a better word as an afterthought. In my opinion, we have to highlight that there are many differing degrees of racism and this is true whether you like it or not.

Matthew Green: it was really nice to be in a room with people that I don't politically agree with but didn't feel the need to have to be necessarily defensive around, particularly when it came to issues facing Black communities. This meeting represented for me the beginning of a much broader and larger platform. One of my concerns coming out of the movement for Black Lives Matter in 2020 was that people would use it as a trend, they’d hold our issues in their consciousness for a moment but then when the news cycle died down, we'd be left with the same structures and institutions that marginalize and continue to oppress and exclude our communities.

BB: Because we are in a moment of deep politicization and polarization both on the political level but then also with people as well. I’m curious about what those discussions were like when there were disagreements and things that people aren't necessarily on the same page about.

Matthew Green: I found myself challenging my own perceptions and conceptions of what Blackness looks like in politics. Going into it, I'll be honest, I had a kind of adversarial perspective towards right-wing Black folks, I didn't think we would find common ground but we did. And when there were disagreements, it is more like a family dispute than a hyper-toxic partisan political dispute. Even when things got heated because we were there for long hours, working through the minutiae, trying to find the right language, the right topics, the right priorities, the right common grounds. I would even go so far as to say that there was still a lovingness in the room, where we have more grace inside that space than I've experienced anywhere.

I have an adage that not all skin folk are kinfolk. Rightly or wrongly, that holds a certain prejudice or bias in conversations because I watch what people do, I don't always listen to what they say. But Charmaine Williams is a great example. That sister I can vouch for. She's a Conservative minister in a government that I detest but I know that in that space we were talking that there’s an authenticity to challenge these structures. I didn’t know her before, so going in I was skeptical but if that can be an example for how parliamentary politics can happen, Canadians would be better served by it.

BB: How does your Blackness show up in your work as a politician? I'm thinking of microaggressions or things you think are issues when maybe some of your colleagues don't see them as issues.

Michael Coteau: I have seen it happen many times in my political experience. I remember bringing up the rise of the African economy a decade ago and trying to push for a strategy provincially, at that time Quebec had one because of the diaspora of Francophones. I remember my colleagues not seeing it as a priority or worthwhile. For example, myself and another trustee pushed the motion and the fight for disaggregated race-based data at the TDSB back in 2006. That was a big fight, we won by one vote and it was the first massive data collection of disaggregated race-based data anywhere in Canada by a major organization. In the debates that we’ve gone through since then, people were saying that racism isn’t real because race is not real; these are arguments that were used, so I’ve gone through all of it.

I’m from Flemingdon Park in Toronto and I can see the division between going from Flemington Park to Don Mills to Leaside, which is a predominantly white school. You can see the differences in opportunities and access for young people. It's always been part of my plan to look for ways to level the playing field and open up opportunities.

Once you started collecting the data, we could say, “We know there are issues.” Up until that point, the fact that 40% of Black students weren’t graduating at the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), the largest school board in Canada, no one knew that number. That became the focal point of the entire debate; everything switched from funding models to program design entirely based on that statistic and looking for ways to benchmark it to put in place programs to see how you can make improvements.

Matthew Green: I would say that, particularly on the left, conceptions of white supremacy by certain folks is still perceived as Neo Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan or instances of violence and they don't recognize the institutions. So, when I challenge these conceptions of how white supremacy looks in Canada, the response for people is often to feel personally attacked rather than consider the institutional structures that perpetrate these power dynamics.

So, in every space I'm in, I have red lines that my colleagues might not have because I've experienced existential threats that they'll never understand. Like our Indigenous siblings in politics, there's constantly a need to have to debate and argue for basic humanity in ways that nobody else ever has to do.

These are toxic environments that are not designed for us. In fact, they were specifically designed for our exclusion both legislatively and structurally but we’re here anyway, we're here despite it and we persist despite those legacies and they remain a challenge. Part of why I'm here is to challenge and dismantle, and disrupt, not to be in proximity of power, not to barter and broker identity politics or block constituency votes but rather to actually challenge the structures and there's a long list of records that show the ways in which my interventions do that. But the process of keeping it real in the House of Commons is not an easy one but we do it, and we do it despite people's discomfort.

BB: What was your reaction to seeing Trudeau in Blackface?

Tony Ince: Let me put it to you that way, I was disappointed, I wasn't shocked because he’d done something similar before in brownface. I can't recall what I‘d said to him when he called me, I think it was something along the lines of “I don't know what you were thinking and you're gonna really have to work hard to build some trust now because you've just shattered a lot of that.”

But again, I have a Dutch colleague, he was an MLA and he’d gone to a Christmas party where he sat on the lap of this guy in blackface. He didn't see anything wrong with it because it's a Dutch tradition to talk about Black Pete and it wasn’t a negative thing. But when you look at the description, he works with Santa Claus but he works with all the bad kids.

The Premier said, ‘You gotta go and talk to Tony.’ So, my colleague came in and really wasn't understanding what he had done. He went on to explain, ‘Well, this is our tradition’ and I said, “Yeah, well, lynching was a tradition, so should we continue to do that?” So, we talked but I don't think he truly even got it but it doesn't really matter. I won't be surprised if somebody does it tomorrow because until our education systems thoroughly involve all cultures and all their real histories we're going to continue to get [this] stuff. Our education systems are one of the key things that allow the status quo to continue.

Matthew Green: The only time that man hears my voice is when I’m heckling him from across the House. We don't get down like that. There are people in our community who want to forgive him but for me, no, this is a multiple-time offender, from the paint to the sock, all of it is disgusting. It just shows the kind of hubris, arrogance and disregard he has for the community. He was there shucking and jiving and doing his thing, and it tells me everything I need to know about him. And this was a grown man, not a child, so that’s it, there's nothing more to talk about. I don't expect a leopard to change his spots. Unfortunately, that level of arrogance and hubris plays itself out in other ways, it’s a level of entitlement.

{https://twitter.com/MatthewGreenNDP/status/1628040664628834305}

BB: If you were to make a pitch to a young Black person who is maybe disillusioned with politics and isn’t optimistic about the future, doesn't think that it's worth it to vote or to get involved. What would you say to them to convince them that it is worth it to get involved and to be informed?

Tony Ince: For any group, if you're not at the table people aren't going to truly understand your perspective and what can be done when you're sitting down and looking at policy and making legislation and laws. Plus, those of us who get to do this, there is so much learned and gathered and gained and such a sense of pride when you're in this role, having the ability to affect some of those changes.

I often say to community members and everyone else, the way I look at it, slavery has done a huge job on us, on our psyche and everything else. It took us 400 years to get here, do we really think [change is] going to happen in an instant. When Marcus Garvey gave his speech, we didn’t realize how powerful what he said was until Bob Marley put it into a song and he talked about emancipating yourself from mental slavery. We have a lot of inward looking we have to do because there is that mental slavery that we're dealing with.

Michael Coteau: In my work over the last 20 years in politics, I've been able to create systems that collect good data, we've been able to establish programs that benefit Black youth, we've put in alternative measures to reduce the representation of Black, Indigenous and other groups within the justice system, we've put in place environmental policies to lower our carbon emissions where asthma rates have dropped. I've seen real-life change for people, even the federal government’s funds for entrepreneurs, creates a whole new ecosystem.

These things are real, they make a difference and they actually contribute to the health and well-being of the Black community in many ways. Governments can help create and support these entities and initiatives, or they can eliminate them, which we have seen in the past.

When we look at statistics, there are a lot of discouraging numbers that are out there, it's true. However, at the same time, the only way you're going to challenge a system you may not trust or that doesn't do well is to use the mechanisms that maintained and created it to actually bend it into a workable shape for the communities that you want to help. I'm living proof that you can get involved in politics and make a difference.

Read part 2 of the series here:

They Made History: The Firsts Who Don't Want To Be The Last

Read part 3 of the series here:

Beyond Partisan Lines: These Black Politicians Can Still Agree On One Thing

By

By