Sometimes it’s hard for people to wrap their minds around it, but my family has been rooted in Hamilton, Ontario (nicknamed “Steel City” due to the steel companies that have historically resided here) for around 110 years.

My great-grandparents chose Hamilton as the place to raise four Black daughters, establish themselves within a thriving community, and build a haven they would call home. My great-grandparents and other Black families, before arriving in Hamilton, traveled through areas like Windsor, Chatham-Kent, Stratford, Dresden, South Buxton and Merlin, by way of the United States.

When the Fugitive Slave Act passed as law in 1850, the northern States remained an open hunting ground for “freed” Black people to be kidnapped back into slavery. Approximately 30,000 Black people (African/Caribbean/Black Indigenous descent) fled north to Canada. Hence, how my grandmother’s ancestors came to Canada.

But Black history within Canada is often quietly placed behind a door, hidden away from mainstream thought or acknowledgment. Canadian history tends to paint a very benevolent picture of it’s past. However, the first reported “race-riot” that occurred in North America, happened in Shelburne, Nova Scotia on July 26, 1784. The riot was ignited when a mob of about 40 white Loyalists demolished the home of a Black preacher named David George, who had been an active challenger of the racial hierarchy in Shelburne and Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

This mob also destroyed the homes of about 20 other free Blacks living on the preacher’s land. Despite the violence against the Black community, David George continued to preach from his church. The mob later returned and assaulted the pastor with sticks, chasing him into a swamp. This violence against Black Nova Scotians continued for 10 days, and heightened the racial prejudices following the years of the American Revolution. Thus, many Black families chose to relocate into other areas of Canada.

Along with Irish, Jamaican, and Vincentian ancestry, I am 5th generation Black Indigenous Canadian. My great-grandfather, Robert Harrison, was Black-Chippewa, born on a reservation in the United States. Establishing roots across southern Ontario, the Harrisons were a large family of many cousins, before they made a permanent home in Hamilton. My great-grandmother was Edith Lewis-Robertson. My father believes her family may have had roots in the Carolinas. Edith married Robert, and was 16 years old when she gave birth to her first child, Fern; my grandmother’s oldest sister.

My cousin, Curtis Bell, author of the graphic novel and educational workbook “Hood Habits”, and mentor to Black and Indigenous youth at 9 Heavens Healing Academy, has been diligent in researching our Harrison roots here in Canada and the United States, and has begun to uncover more pieces of our history. He reminded me that, “our family isn’t just a tree, it’s a forest!”

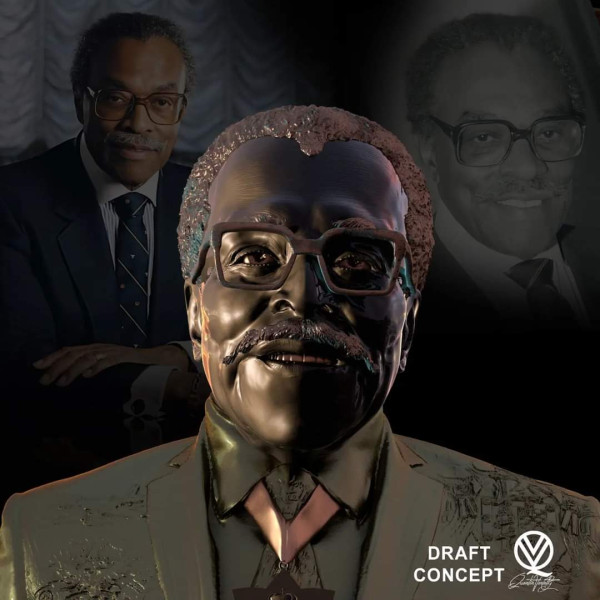

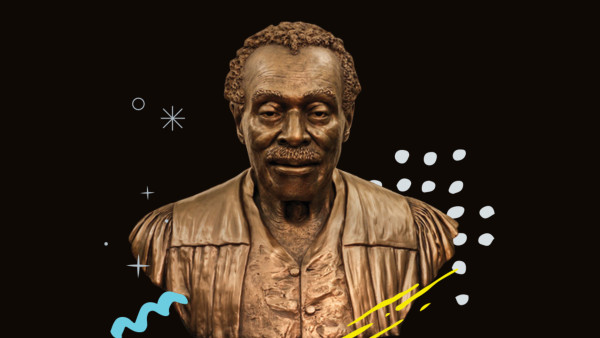

PHOTO: Robert Harrison (great grandfather) and my grandmother Yvonne

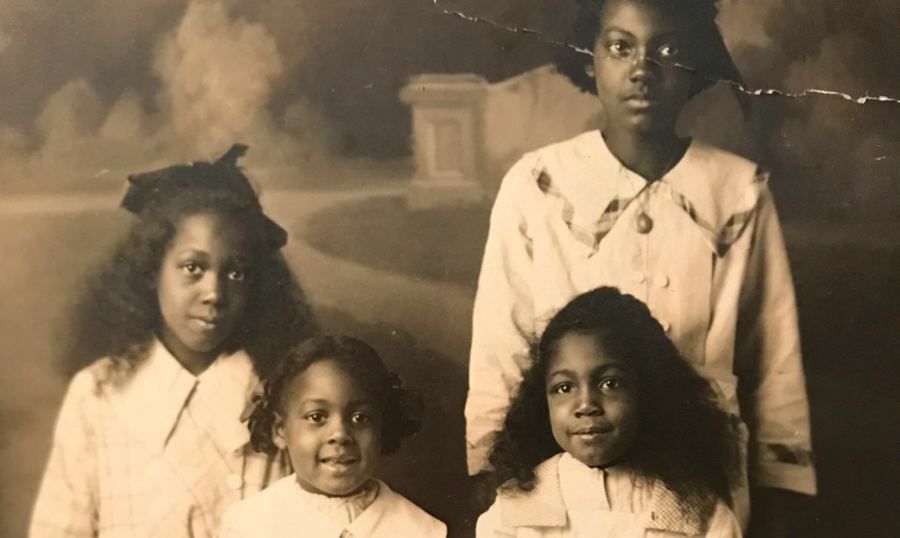

My grandmother Yvonne was born in Hamilton in 1916. She was the youngest of four daughters to Robert and Edith. Her sisters were Fern, Audrey, and Jaunita (Sugar). Fern lived with my family for a short period of time when I was a child, and passed away when I was 13. She was a dignified woman and socialite who loved to sing in various church choirs. She never married. Fern used to give my sister and I handfuls of pennies to buy candy at the corner store at Victoria Avenue and Cannon Street.

My aunt Jaunita aka Sugar, passed away when I was still a child. She too never dated or married and was unable to have children due to health complications. She operated her own business, called Jaunita’s Beauty Salon where she made and sold her own wigs. This would have been in the 1950s, when my father was a child. Jaunita also liked to read tea leaves, and would prescribe herbal remedies to friends in the community. She was tough and a homebody, and spent a lot of time with their mother, Edith.

I never knew my grandmother’s sister Audrey, as she died long before I was born. She looked like my grandmother. Audrey married a man named Ewing Bell (who was also Black-Indigenous), and had one son, named Robert “Bobby” Bell. My father’s only first cousin. Three of the sisters, Fern, Audrey, and Yvonne were often found socializing in the community of Hamilton together, particularly at church, community and Black Mason dances. My great-grandfather Robert was known to carry and use a switch-blade, so it was common knowledge in the city that one shouldn’t mess with the Harrison daughters, and therefore they were deemed “the Untouchables”.

PHOTO: My grandmother and her sisters (Audrey, Yvonne (smallest), Jaunita, Fern (tallest)

My great-grandfather Robert, was a railway porter for most of his life - one of few jobs allocated to Black men in Canada during that time. Yvonne and Fern would walk to the train station to greet him on his return trips. My father tells me Robert (nicknamed Robbie-Rob) was a quiet man, and during his time at home, he would tend to the gardens, prepare fish and food, read and stay quiet amongst all the women in the house. My great-grandmother Edith ran the house with small businesses on the side. One of those being a boarding home for Black entertainers to eat and sleep at night. They would come to Canada to perform, generally for white audiences (racism disallowed these same Black performers from sleeping in Toronto and Hamilton hotels and motels). Duke Ellington was one of those entertainers that Edith would have taken in. My grandfather Lincoln Alexander, being a lawyer at the time of Edith’s passing, confirmed that she had full ownership of her Victoria Avenue home. Lincoln was also surprised to find out that my great-grandmother had saved fifty-thousand dollars in her bank account!

Between my great-grandmother and aunts, they baked and cooked soul food, sometimes ate by candlelight, and found a home at the historical Stewart Memorial Church. I remember their home always smelling sweet or savoury or like frankincense, and always sounding like blues and jazz. They opened their home to my grandfather Lincoln’s mother, Mae Rose Royale (originally from Jamaica) when she struggled with her housing arrangements. My father tells me that some white folks would cross to the other side of the street on Victoria Ave North, so they wouldn’t have to walk by the Black women sitting out on their front veranda. My great-grandfather Robert would be watering the grass on the big front lawn - just watching everybody. This makes me laugh. It would have been considered a “unique thing” for white people to see a Black family living in a big house in the centre of the city.

My grandmother Yvonne grew up in Hamilton, witnessing the KKK parade audaciously through our streets. She and her sisters would have been witness to the burning of crosses along the Niagara Escarpment during the 1920s and 30s. My grandmother Yvonne worked as a laundry maid (while my grandfather Lincoln was in school) where she was often met with racial discrimination. She also worked as an elevator operator, where she was sometimes met with harassment from men who worked in these buildings.

PHOTO: My parents Keith and Joyce with my grandparents Lincoln and Yvonne Alexander, and my sister Marissa and I.

When my grandfather, the Honourable Lincoln M. Alexander became the first Black member of parliament in Canada, my grandmother would find herself being followed home by police on her social nights out. Once, a Jehovah’s Witness rang their doorbell, to which Yvonne answered and was asked “Would the lady of the home be in?”, assuming my grandmother was the help. She would respond with a simple “No”, and shut the door. This happened to her many times. My grandfather Lincoln went on to become the first Black Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, and was later asked to fulfill the positions of Governor-General, and director of CSIS. However my grandmother Yvonne objected on his behalf for both positions, fearing their life would be in too much danger, as a Black public figure, had he taken on such roles in the government during the 1990s.

Despite the experiences Yvonne had, she accepted her public role graciously, and acquired many accolades of her own such as being a Past Matron of the Order of the Eastern Star, Officer of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, Honourary Patron of the Women’s Canadian Club of Hamilton, Honourary President of the Provincial Council of Women, Canadian Bible Society Women’s Auxiliary, and the IODE Provincial and National Chapters. My grandmother loved to garden with Lincoln, volunteer, read her Bible and other novels, cook delicious food, hide dark chocolate around the house; the candy dishes were always full. My grandmother Yvonne was 6 years older than my grandfather Lincoln, and supported and helped to build his life-long career. Lincoln chose Hamilton as his hometown because that’s where Yvonne was. They had a 50-year long marriage together before my grandmother passed away in 1999.

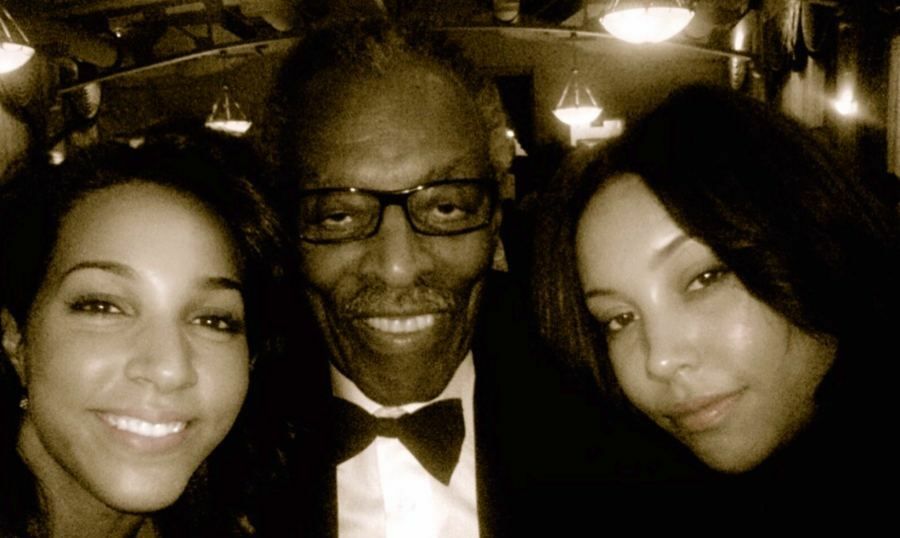

PHOTO: Lincoln Alexander and his granddaughters, Marissa and myself (right)

My father, Keith Lincoln Alexander was born in 1949. As a child, he was often chased home after school by little white boys who didn’t like his skin colour. He would fight his way home. Before Canadian immigration opened to Caribbean and African countries, my father was one of the few brown-skinned, Black boys in the city. My childhood in comparison, was not the same. Mostly, my younger years felt safe and protected in a way that my dad did not experience growing up in this city. Recognizing my family lineage, the opportunities my parents had, being “multi-racial” in relation to my own identified Blackness, I was not racially targeted in the same way my browner skin-toned family members were. However, the first time I was called the “N-word”, I was 10 years old; a grade four student. Despite certain privileges I have acquired in my life, none of them have veiled me from racial hatred as a child or an adult. In present times, my little brown-skinned goddaughters, and other BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) children and youth in our communities, are continually being made very aware of their “non-whiteness”, at school, and the violence and worldly things that are projected upon them when they leave their homes.

The intergenerational trauma is real, heartbreaking, and devastating. It has created a fiery response from those who are no longer willing to let these acts against humanity remain the same and unchanged. We are still witnessing some of the same subjugation that our ancestors felt, only a generation or so ago. Out of those ashes, we have not stopped rising. Today, we continue to see grand levels of excellence across many spectrums within the global Black community, and we can recognize that Black excellence, the excelling of Black people across nations, is a form of protest, activism, and freedom. It is our right to be.

Erika Vanessa Alexander is the eldest granddaughter of the Honourable Lincoln M. Alexander, and on behalf of her grandparent’s legacy, she acts as the family spokesperson. Erika engages in public speaking and story-telling of her family’s past, Black history and anti-racism presentations, and annually promotes the celebration of Lincoln Alexander Day across Canada. Erika has acquired degrees from McMaster University of Hamilton, in Political Science and Religious Studies, and a diploma from the Institute of Traditional Medicine of Toronto for traditional Chinese acupuncture and medicine. Erika is currently working towards celebrating Lincoln Alexander Day in January 2022, signifying Lincoln’s 100th birthday, and the release of a special commemorative writing project to honour her family.

By Erika Vanessa Alexander

By Erika Vanessa Alexander