“There is a stigma that stops Black people from wanting to live there,” says Sheldon Williams, a Black resident of Halton region and Vice President of the Canadian Caribbean Association of Halton (CCAH); a 43-year-old non-profit organization whose passion is to build strong, successful Black people in the Halton area.

"Black people continue to be the vast minority in Oakville, while the majority of the community is white,” says Williams. "Financially speaking, people who live in Oakville tend to be in the upper echelons." In 2016, Statistics Canada recorded that Black people made up 2.9 percent of the population of Oakville’s 191,720 residents. “There are not a lot of people of colour in this area,” says Williams. “Being a Black person in Oakville is almost a crime, and this is why the CCAH has partnered with the Police Services for our Youth Leadership Program.”

The program runs three to four times a year for teenagers between 12 to 15 years old. “I don’t have positive examples of police in my life, but CCAH is trying to change the narrative,” says Williams. The organization hopes to eliminate fear of discrimination in Black youth with this partnership and to demonstrate positive examples of policing. But that fear is very real. Williams recalls his own personal experience with the police as a college student in Oakville. He was out with friends after school when a group of white boys called his friend the “N-word." The verbal assault turned physical quickly and the police were called. “The cops showed up, and instead of arresting the [White] guys, they threw me in a drunk tank for the night...no one helped me, and I felt like I did not belong here,” says Williams. “I was not happy for a long time, but dealing with the sergeant in Halton one-on-one, I have developed a little more trust."

So where does the history of Black people in Oakville begin? According to records kept at the Oakville Museum, over 40,000 African-Americans migrated from the United States to Canada from 1850 to 1861 via the Underground Railroad. These freedom seekers came to live in various parts of Ontario through the official Port of Entry, Oakville. “Most people would think that the escaped slaves who settled here were destitute, but that is not entirely true,” says Robert Gardner, a retired professor who operates Turner Chapel Antiques and Appraisers with his son, Jed. “Freed slaves had skills, became very wealthy, and owned large homes and farms,” asserts Gardner.

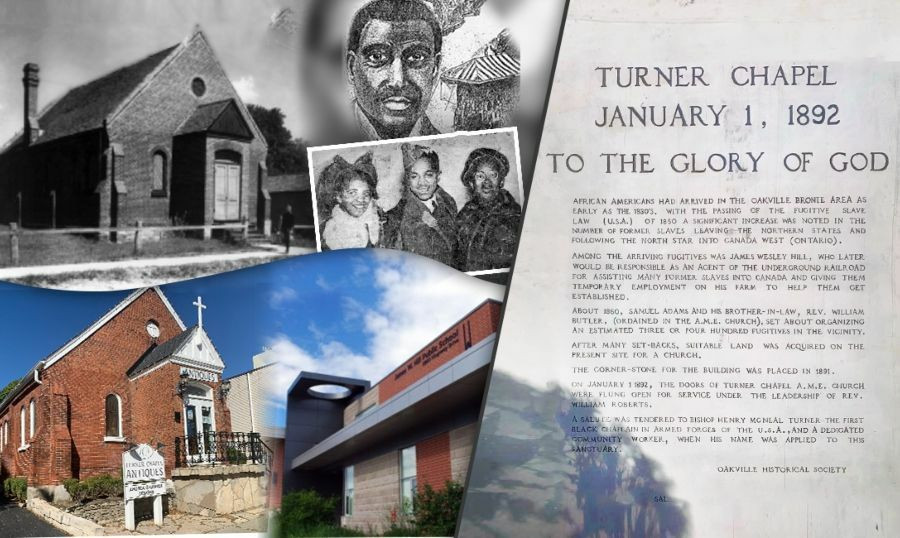

Turner Chapel Antiques and Appraisers, a 1000-square-foot antique shop in Oakville, was formerly The Turner African Methodist Episcopal Church. Constructed in 1892, it was founded by Samuel Adams and his brother-in-law Reverend William Butler, free African-Americans. The 129-year-old pillars of The Turner Chapel Antique and Appraisers still stand strong today, as a heritage site located on 37 Lakeshore Road West in Oakville.

The Johnsons, the Wallaces, and the Duncans became prominent members within the community.

Branson Johnson, a freeborn African-American arrived in Oakville with his family in 1863. He lived a block west of The Turner African Methodist Episcopal Church and worked on a train that ran between Toronto and Detroit. His Freedom Certificate which can be viewed at the Oakville Museum was discovered in an heirloom pocket watch a hundred years later by his grandson.

James Wesley Hill, a strawberry farmer in 1850, also known as “Canada Jim” and “Conductor” led nearly 800 African Americans to Oakville along the Underground Railroad. Today, The James W. Hill Public School is named after him and the house where he lived still stands at 457 Maple Grove Drive.

John Cosley, was an inventor who owned The Bee, a short-lived newspaper printed on a hand press that he had made himself.

The Duncan Family, particularly Alvin B. Aberdeen Duncan, created a legacy that is etched into Oakville’s history. The grandson of Samuel Adams, he served as a radar operator for the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War. He would later own Al Duncan Television and became a local historian, particularly in African-American history. His family still lives in the Halton area today.

“The areas that had Black people clustering during the Underground Railroad eventually moved on because they didn’t feel they had the working opportunities,” says Lawrence Hill, author of the internationally acclaimed The Book of Negroes, and Black Berry, Sweet Juice - a memoir of his struggle with racial identity growing up in North York, Ont. In the latter memoir, Hill documents an interview with Alvin Duncan, the great-grandson of Adams, who was there when the Klu Klux Klan came to Oakville on February 28, 1930. “It is not a phenomenon related only to Oakville,” says Hill. Around the same time in the United States, many Black men were being lynched by the KKK, forcing southern Black people to flee to the north in fear for their lives. “Seventy-five hooded Klansmen assembled in Hamilton and drove in a procession to Oakville,” Duncan recounts in the book. Duncan described to Hill the efforts of the Klan to prevent the marriage of a Black man, Ira Johnson, and a white woman, Isabella Jones. “They threatened that if Ira Johnson was ever seen walking down the street with a white girl again, the Klan would attend to him.”

Hill included excerpts of The Globe and Mail’s front-page story that read, “There was not the semblance of disorder, and the visitors’ behaviour was all that could be desired according to Chief David Kerr of the Oakville Police Department.” During the altercation, the police did not interfere with the demonstrators and said that the Klansmen did not destroy any property or harm anyone. In a twist of events, Ira Johnson would later claim to be of Indian descent; trading one racial identity for another, Hill’s book revealed.

Tracing the history of Black people in Oakville clearly shows significant Black success in the area but also significant threat and real danger. Hundreds of years later that threat is still apparent. The socio-economic status of Black families in Oakville are held under a microscope that suggests either you are too poor to live here or can only afford to live here as a result of illegal activity.

A study of Black youth and their families in Oakville found that generally Black people did not feel welcomed or respected in Oakville. It is more likely for a Black person to get pulled over by the police in Oakville in comparison to Mississauga just 10 minutes away.

But signs of Black success and the impact Black people had on Oakville are everywhere, yet seem to be ignored or completely undervalued.

Robert Gardner smiles as he speaks of his introduction to Alvin Duncan during the inauguration of Turner Chapel Antique and Appraisers in 2003. “I asked Mr. Duncan if he felt that this was a good use of the property and he said it was,” says Gardner. “If we had not bought it, it would have been destroyed, which would have been a huge loss for the community.”

By

By