Being the only Black person in predominantly white spaces has some funny consequences. It changes you. It normalizes inappropriate behaviours that are sometimes shameful, heartbreaking, or exhausting to experience and later, reconcile. The racism I experienced growing up in the Canadian prairies was complex and multi-dimensional. The most insidious outcome of this problematic environment was how I internalized this oppression and allowed it to compromise my perception of myself and of other Black people long after I left. With each experience of invalidation and marginalization, this internalized racism reinforced itself. It became a core tenant of my identity and manifested in various, unexpected ways – including in my romantic life.

When romantic curiosity picked up in secondary school, I noticed a trend. Despite being athletic, intelligent, and as out of touch with fashion as the rest of my adolescent friends (think brightly coloured BDG cigarette pants, angsty raccoon eyes, and crispy 400°F hairstyles), something wasn’t adding up. Zero romantic shenanigans were coming my way. Until my last semester where I swapped spit with a boy who refused to look at me ever again, my crowning achievement in the romantic department was a pacifying “it’s not you, he just doesn’t like people who look like you” comment from a classmate.

These slights, plus the continuous subtle and overt reminders that Blackness was both foreign and unattractive, left me desperate for attention. Some encounters were positive along the way, but the two relationships I fully opened myself up to while in Edmonton, at best, problematic.

Consider my first ex - a white man from a mid-sized city in Alberta. He and I met at my first restaurant job. I was a host, and he was a bartender. Four years older than me, he made it clear that he was waiting for me to celebrate my eighteenth birthday before he made a move. Charming, I know.

His “charm” translated to a lot of socializing with his friends and family. Clearly, I was the first Black woman many of them had ever interacted with. As a result, long weekend camping trips with his friends or overnight visits to his parents’ house left me exhausted. The ignorance and microaggressions were never-ending. Sadly, I didn’t know better. I thought it was completely normal that his friends left me on edge, that I could hardly last more than an hour in a room with his parents before needing to excuse myself, or that my ex was willfully oblivious to my consistent discomfort.

Regardless of these major flags, I stayed. My low self-worth and desire to be desired carried me for nearly two years. The breaking point was a phone call where he enthusiastically shared a story from his family’s recent games night. While playing a round of Scattergories, my ex, his brother, and their parents proudly came to the winning conclusion that an appropriate response to the prompt “Things that are Black” was “Kadima”, my family name. With that, I was done.

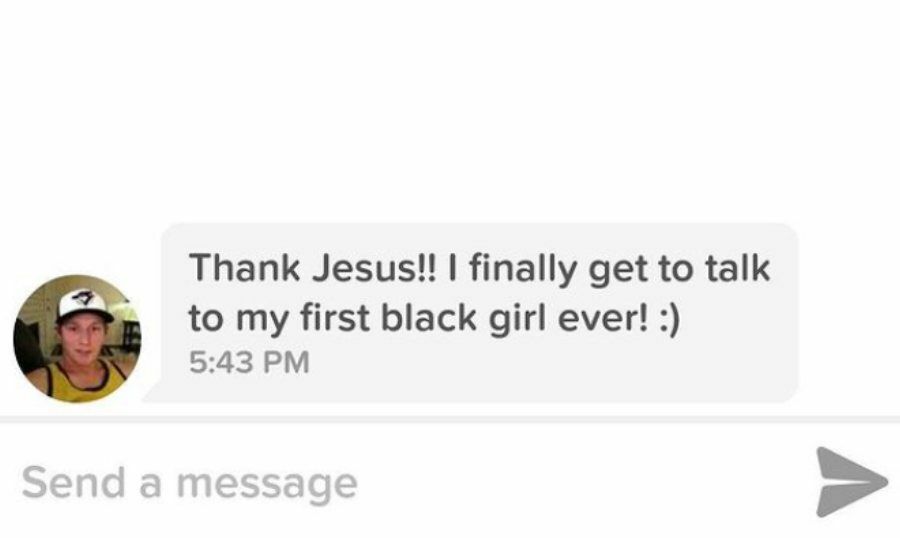

After a period of being single best described by Hadiya Roderique’s phenomenal article “Dating While Black” and this screenshot, I met my second mediocre white ex.

Screenshot from a Tinder message received in January 2016.

His pride in manipulating the University of Alberta’s academic enrollment system to secure a second term as a student politician, instead of entering the workforce like the rest of his graduating class, should’ve been a warning sign.

But by this point, all it took to pass my unconscious criteria for potential romantic partners were the following four attributes: white, male, around the same height as me, and an expressed interest in getting in my pants.

This relationship took every flag from the prior and waved it ten feet higher. The trauma from this period took a long time to not only acknowledge, but also to come to terms with. Only recently did I become comfortable calling these two years what they truly were: an emotionally manipulative relationship with an insecure, gaslighting narcissist.

I suffocated. The few boundaries and expectations I expressed were twisted and invalidated. The small voice I began to build while in undergrad shrunk repeatedly. Faking was so second nature by this point that the meaningful physical intimacy I learned to experience years after this relationship, genuinely surprised me. I learned to pacify instead of assert.

Like my first relationship, it took a jarring experience to end this one. Done with my revolving roles of validator, victim, and therapist, I tried to break up with him in early 2018. Instead, he convinced me into a four-month break where we “agreed” only to date people who weren’t mutual connections. At the end of that period - most of which I spent overseas - I discovered he cheated our one rule by publicly dating an obvious, mutual contact of ours. Seething in indignation, I finally left him. Affirmed knowing that, now graduated, I would move to Toronto later that month to begin a new chapter.

Preparing to leave Edmonton, I made my rounds, sharing the news and saying goodbye to all of my hometown friends. Those conversations often involved the explanation of what happened with my ex, especially considering that many of my friends saw him with his summer fling and knew something didn’t add up. Of these explanations, the most memorable ended with a close friend looking at me severely while saying “Gwenna, if the first person I see you dating in Toronto is another tepid white man, I will fly across the country to shake some sense into you myself.” It was a reasonable statement. From my Prairie-based, ostracized Black woman’s frame of reference, Toronto was the land of romantic milk and honey. I left Alberta assured that I wouldn’t continue the habit of dating the kind of mediocre men that would make Ijeoma Oluo shake her head. My dating archives represented the relationships I thought I deserved. Now, I knew better.

September 1st, I landed in Toronto with four boxes and my sweet guinea pig, Lady, tucked under my arm. Two young women ready to take on the city, heal from their traumas (Lady’s was the flight, mine were the last 22 years), and find ourselves some spicy melanated people and piggies to love.

I was ready. The dating app trifecta (Tinder, Bumble and Hinge) were firing on all cylinders and I’d be damned if I left the house unprepared for a Gabrielle-Union-in-the-mid-2000s-level spontaneous romantic encounter.

Yet, six months into living in Toronto, my recent dating archives were full of the same. Was this city broken?

Fearing a literal shakedown from the same Edmonton friend, I started to reflect. There was no shortage of Black folks in the city so Toronto wasn’t the issue. Maybe it was the people on the dating apps? I reopened Tinder and started swiping furiously until it hit me. Even in my “analysis”, the only profiles I paused and gave any consideration to were either white or white-passing men. My brain didn’t even process non-white profiles. A pop of melanin on my screen and I’d swipe by.

My behaviour shocked and disappointed me. Unbeknownst to me, the racism I experienced in Edmonton was so internalized I subconsciously projected it onto the Black and Brown people around me. The only folks I saw as potential partners or at minimum, worth dating, were white. My dating preferences were grossly whitewashed and it was my responsibility to fix it.

After years of dismissal, fetishization, and abuse, it was time to re-write my narrative of Black love: of myself and of others. This process was slow and uncomfortable. I had to process the traumas I experienced and I had to recognize how fractured my sense of self was. I explored my understanding of my body, its worth, and its beauty. I learned to be by myself - a lesson that isn’t hard when you’ve just moved 3,400 km away from home. With time, I started to see myself as worthy of love and respect.

I reflected on how entangled my definitions of beauty, success, and security were with whiteness. For most of my life, I existed solely in disproportionately white spaces. My neighbours were white, my instructors were white, the wealthy and happily married people in my congregation were white, my classmates were white, my employers and colleagues were white, and so was every success story in the media I consumed. It was time to normalize Black excellence.

Privileged enough to travel, I committed my next trip to the continent, visiting Nairobi, Abidjan, Cape Town, and finally Johannesburg, where I stayed with family. I prioritized my Black coworkers and focused on building a Black employee resource group for us within our workplace. I watched, read, and listened to more Black media. Finally, I became more intentional in my dating: slowing down on apps and ensuring I read every person of colour’s profile from start to finish before swiping. In person, I initiated more interactions with people of colour at bars and other social spaces. I wasn’t opposed to dating white people, but I knew I had to intentionally focus on folks of colour to restore the balance.

Although some of these actions may seem insignificant, they changed a lot for me. My dating diversified beyond just race and ethnicity. Proudly, I acknowledged and embraced my bisexuality - something I never explored in Edmonton due to fear of rejection and dismissive responses from those once close to me.

Throughout this period, I slipped up occasionally. I found myself in relationships with misaligned expectations and incompatibilities, With confidence, a stronger sense of self-worth and a greater ability to act on my needs made those “situationships” easier to leave. Although it occurs less frequently than when I was in Edmonton, I shut down anything akin to “Wow, you’re really pretty for a….” before it saw the light of day. Things had truly changed.

My Edmonton upbringing resulted in trauma and deeply internalized acceptance and reinforcement of the racism I experienced. I’ve worked hard to dismantle and unlearn the damage from that trauma, especially when it comes to race-based dating preferences. It’s been satisfying to date folks with similar identities or lived experiences to me. For the people who say “I only date (insert race or ethnicity) people”, I ask you to challenge yourself. Yes, race-based dating preferences can be a response to trauma and that’s a different, valid story. In her insightful MTV Decoded episode, “Does Race Affect Your Dating Life?”, Franchesca Ramsey said it best, “People of colour not wanting to date white people [can be] a defense mechanism to avoid being fetishized or overt racism.” This I understand. But if your preferences are arbitrary or your justification goes as far as “I dunno why, I just do”. It’s likely time to check yourself and re-evaluate what biased and potentially racist views might be holding you back.

By

By