When writing these songs, I often thought of how being Black online comes with a unique set of challenges. Much of what I rap about on the record relates to the difference between reality and perception and that contrast is never more glaring than on the internet.

When people from other cultures throw on a Black avatar and start using AAVE (African American Vernacular English), it can feel like a sort of digital Blackface. This is often all it takes for someone to pass on social media, bestowing instant credibility to users commenting on Black discourse, whether they deserve it or not. But those same people who cosplay as Black folks online would never want to trade places with us in the real world.

Trends often start on Black Twitter and filter out to the rest of the population. The default format for a viral meme usually involves a moving image of a Black person that draws from our effortlessly expressive culture.

{https://twitter.com/RealityByAshley/status/1764664301044760883}

This can initially be flattering. But as the meme picks up steam and leaves the safety of our community, it can begin to feel extractive and exploitative, especially when the original context inevitably fades away with time.

When I tweeted about the double standard in the treatment of George Floyd protestors in 2020 vs what happened with the Freedom Convoy in 2022, it went viral. As my words bounced across the web, taken out of context and subjected to bad faith arguments, I was subjected to countless racist replies, messages and threats.

{https://twitter.com/cadenceweapon/status/1488157152925659146}

I’ve seen a similar phenomenon happen to journalists who are women of colour. Depending on your racial identity, just stating your opinion online can be enough to unleash a firestorm of vitriolic bile. This is something you’re unlikely to experience if you’re a white man.

One day a friend sent me a promotional email that they’d received from a clothing company. The business was promoting a holiday sale. Peering back at me through the screen was a younger version of my own face. They had used a childhood photo of me smiling widely and holding a Christmas present. This was all done without asking to use my likeness or compensating me in any way. A white-owned company stole my Black Boy Joy to sell their products. They lifted the photo from an Instagram post I had made many years ago.

What happened to me is similar to how “on fleek” quickly became a common feature in advertising language, used without crediting or paying the original creator. There is a broad assumption among some sectors that our minds and bodies are public domain. Our slang and wordplay regularly filter into the public consciousness and the waiting hands of the inherently swaggerless: politicians, corporations, and brand mascots. And by the time it makes it there, we’re already moving onto something else, out of necessity.

{https://x.com/IHOP/status/524606157110120448?s=20}

{https://x.com/dominos/status/605862973433737216?s=20}

{https://x.com/virgiltexas/status/588428352396075008?s=20}

Social media has been one of the greatest organizing tools of all time. We saw the wide-reaching connective possibilities of platforms like Twitter and Instagram during the George Floyd protests and the rise of Black Lives Matter. People like Deray Mckesson and Desmond Cole become public figures with powerful social media presence. It was heartening to see how much money was being raised online to support Black organizations. I personally released a remix album in 2020 and gave hundreds of dollars in proceeds to the Canadian Association of Black Journalists.

On the other hand, there was something distasteful about the wide dissemination of videos featuring Black people being arrested, injured or killed during this time. While these protest movements wouldn’t have had the same potency without cellphone camera footage, the media broadcasting and repeating these images and videos of Black death on a 24-hour loop became exhausting over time. It felt as if they were trying to normalize and profit from these images, rather than illuminate the struggles that led to them.

This is the paradox inherent in being online as a Black person. The internet is fuelled by our creativity and ideas, whether it’s through memes, dances or our music. The web would be a less fun place without us. And social media platforms have provided us with the ability to band together in an unprecedented way. But the commodification of Black trauma has become a regular part of online life, our misfortune providing the fuel that keeps the outrage machine churning.

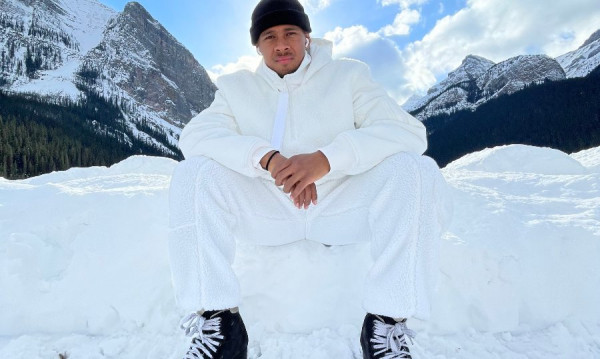

{https://www.instagram.com/p/C3521Jkv_Ow/?hl=en}

My intention with my album and this piece is to remind us all of our agency in how we engage with the internet. Everything I mentioned before represents the additional psychic baggage that all Black folks have to carry when we go online. Since tech companies rely on our addiction to their apps to profit, it’s important to be reminded that we have the freedom to disengage from the online echo chamber if it isn’t feeling good. Being more mindful about my internet usage has been good for my mental health. Let this be your reminder to take a step back from the swirling morass of identity politics that comprises the internet and be more intentional about how much of ourselves we give to the machine.

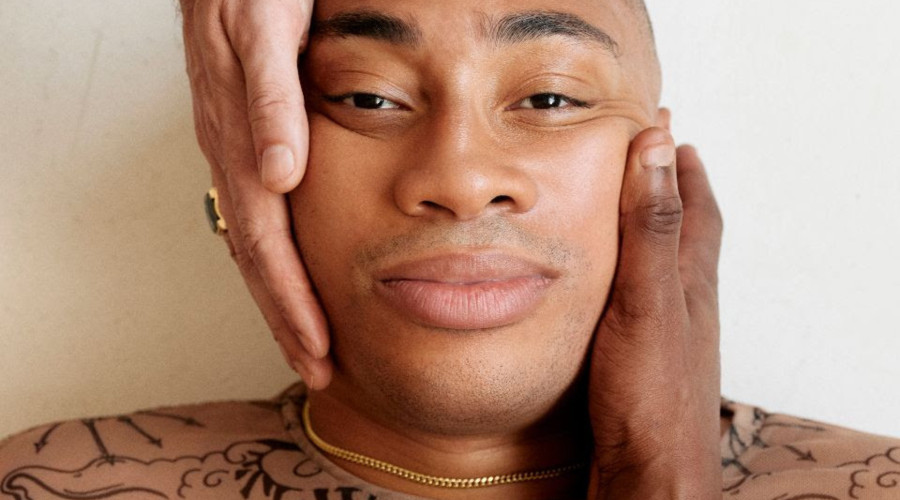

Cadence Weapon’s album ROLLERCOASTER is out April 19, 2024

By Cadence Weapon

By Cadence Weapon