In recent weeks leading up to the magic of the Gala, my curiosity has been fueled. I deeply contemplated the rich narratives of identity, resilience, and heritage that shape Black style across the diaspora.

And while I wasn’t focused on who got it right, I watched the Met with the feeling of wanting more. While many absolutely nailed it (hello Janelle Monáe) I felt like many missed the cultural mark.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/DJW7fWRufnd/?hl=en}

What is Black dandyism about? Well, imagine a time when many Black people were told they weren’t supposed to stand out or be seen as stylish or important. Despite that, some Black people decided to dress up in their best clothes—sharp suits, fancy hats, and polished shoes—and walk proudly through the streets. They did this not just to look good, but to show the world they deserved respect and dignity, no matter what others said.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/DJMvNNiNbzt/}

Think of it like wearing a bright, bold flag in a sea of gray—Black dandyism was our way of saying, “I am confident, I am valuable, and I am here to be seen.” It’s a story of using fashion as a form of resistance, turning personal style into a powerful act of self-affirmation and pride.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/DJSYn9CvqeR/?hl=en}

At the core of Black dandyism is a sense of rootedness that transcends geography and time, celebrating the deliberate craftsmanship of personal presentation. From Congo’s Sapeurs with their vibrant suits to Black American and Caribbean “swag” —a word that encapsulates a cultural presence that transforms clothing into a language of identity and belonging—the threads of heritage are unmistakably woven into every stitch.

One story that continually echoes is that of Andre Leon Talley, the trailblazing first Black fashion editor of Vogue, who often reflected on his Southern roots and their influence on his style. Talley once said:

“What matters is a sense of place, a sense of self… At the end of the rainbow that has led me to success in fashion, I find that my deepest roots ground me.”

Cultural Continuity in Fashion

These connections are not mere coincidences but evidence of an enduring cultural continuum. For generations, Black communities have practiced self-fashioning as a form of resistance, celebration, and survival, often without formal platforms or academic recognition. When we see Black dandyism highlighted in institutions like the Metropolitan Museum, it culturally validates in a different realm what many have been practicing for years. This is precisely why I launched Threads of Heritage—a cultural storytelling initiative that documents and elevates these lived experiences.

Threads of Heritage serves as both archive and celebration: a space where we honour the rituals of self-presentation as living technologies of cultural resilience. Through this platform, participants become custodians of their own stories, creating cultural heirlooms that affirm identity and foster community. Fashion, in this context, becomes a vital act of cultural embodiment—an everyday art form that preserves ancestral knowledge and celebrates joy amid adversity.

The Rituals of Dandyism and Personal Heritage

Like many Caribbean nationals, writer and cultural observer Zannalyn also reflected on her Caribbean roots connected to the term ‘Saga Boy’.

“This year has me reflecting on how my own understanding of the Dandy is deeply rooted in my Caribbean upbringing and the term 'Saga Boy.' Though we also used the term Dandy in relation to a man in tailored dressing, Saga Boy was often uttered.”

If you have Caribbean roots, I am sure that you have heard the term saga boy or swag. Author Harvey Neptune notes that "in occupied Trinidad of the 1940s, saga boys came into being in the sociocultural consciousness by “putting on performances of elegance and excess. Saga boys challenged that which was prescribed for their race, class, and gender.”

Growing up in Saint Lucia, I witnessed saga boy and swag—Black dandyism in everyday acts. When I think of Lady Dandyism, I think of the ritual of getting dressed for church. It’s a ritual right down to what you wear.

Our everyday cultural practices represent time-long systems of knowledge that deserve serious scholarly and cultural attention. This is not simply about fashion but about understanding how communities have fashioned themselves through both adversity and celebration.

I think about my grandfather’s outfits just for sitting on the porch, his hat and signature four-pocketed shirt pressed and properly buttoned up. It was a small but significant act of self-fashioning and cultural affirmation that spoke volumes about how he viewed himself in the world, or maybe how he felt the world ought to see him.

My father continued this tradition: laying out his clothes the night before, carefully grooming his face, polishing his shoes—rituals of care that connected him to his ancestors’ pride.

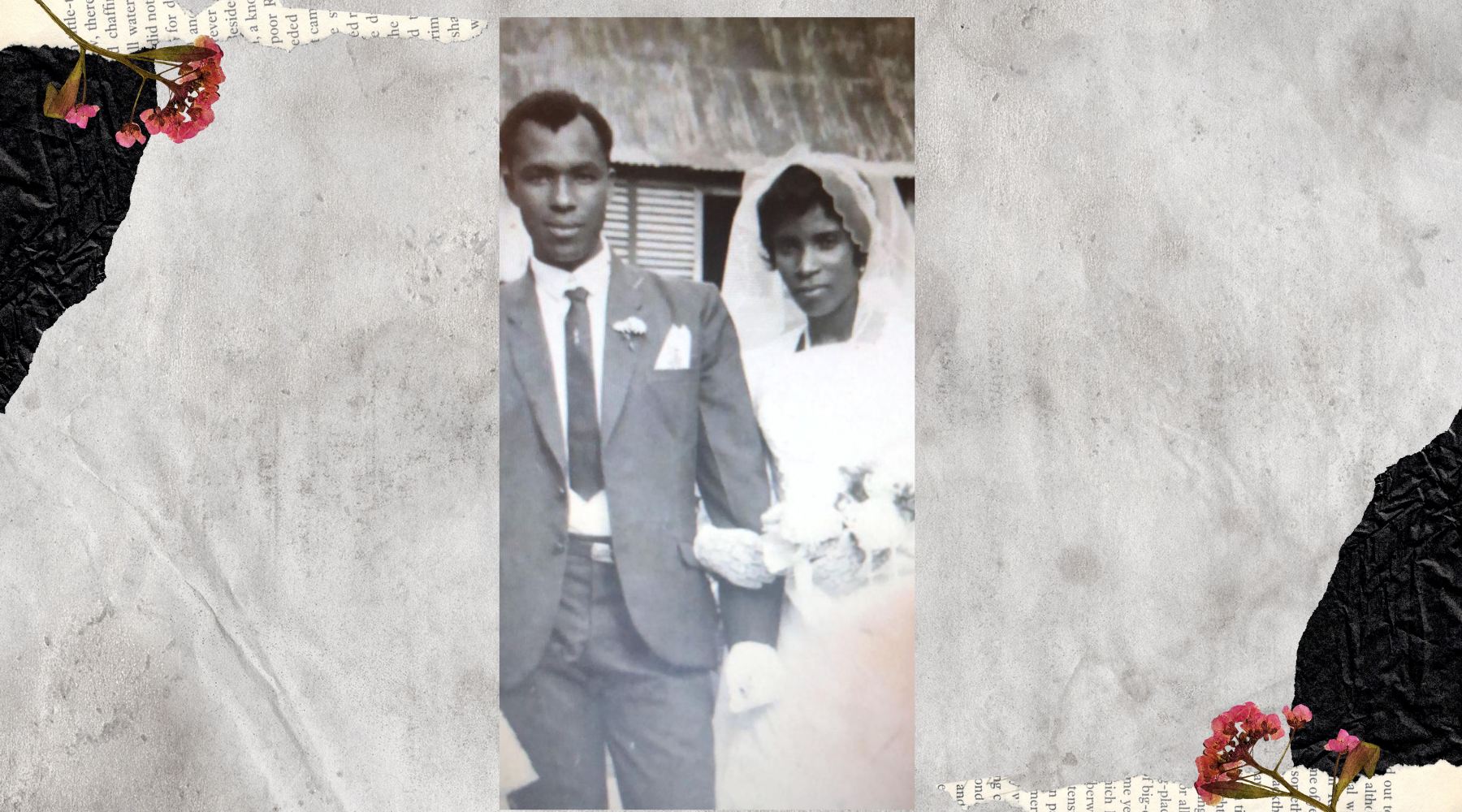

My favourite photo of my father is one from my parents' wedding day. He's wearing a Vogue-worthy suit, white gloves, and a confident stance, which captures this cultural language of deliberate self-presence. These moments are not mere fashion choices but rituals rooted in community, history, and self-respect. The stance and the fit both represent the embodiment of dandyism.

My parents on their wedding day

My parents on their wedding day

Hybridity and Psychological Capital

Scholar Monica L. Miller, in her groundbreaking work Slaves to Fashion, emphasizes that Black dandyism is not imitation but a form of cultural interrogation—an “everyday technology of identity construction.” This perspective illuminates how fashion acts as a form of psychological capital, depositing cultural pride, confidence, and resilience into our collective consciousness.

The Met’s exhibition, organized into twelve facets—Ownership, Presence, Distinction, Disguise, Freedom, Champion, Respectability, Jook, Heritage, Beauty, Cool, and Cosmopolitanism, mirrors what I observed in both my Dad dressing for church or any outing, and my grandfather's careful ritual of dressing for the patio.

From Gala to Everyday Celebration

While many of us had our own personal insights on this year’s Met, the theme invites personal storytelling—I also look forward to engaging with the upcoming Styling the Dandy Within event at the NIA Centre for the Arts in Toronto. This moment in history transcends fashion; it has sparked a conversation on how we reclaim our identity, reminding us that each garment and ritual is a chapter in our ongoing narrative of self-sovereignty and identity.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/DI2JyXwyTsG/?hl=en&img_index=1}

As you scroll and share your favourite looks and critique the ones you don’t like, remember to bring your inner dandy to the conversation. I invite all to consider the following: What traditions, styles, or rituals from your cultural heritage do you wear daily? How do they serve as anchors or symbols of pride? And how might you celebrate these threads of history in your everyday life?

Remember, fashion is not just about aesthetics—it’s a language of legacy. As we watch, critique, and celebrate on the red carpet, let’s also recognize the deeper stories woven into every stitch. Be the narrative. We are, after all, the authors of our cultural plots—one carefully chosen garment, embodied one step at a time.

By

By