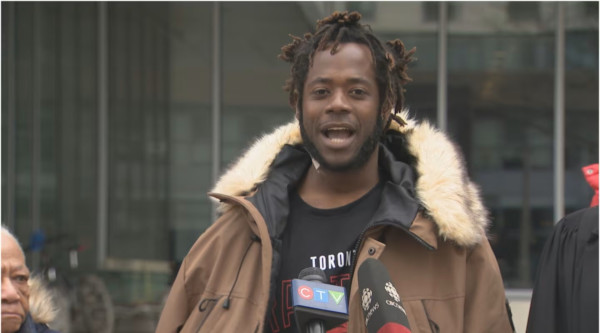

Yazdan Khorsand immigrated to Canada from Iran in July 2008 and became a Canadian citizen in 2013. Seeking a career in law enforcement, he earned a Police Foundations Diploma with honours from Trios College, which named him Student Ambassador Leader of the Year. He graduated from a Basic Constable Training Program and received various other certifications and training relevant to policing. He has also volunteered with Crime Stoppers since 2019 and founded a community organization to support the homeless.

When he applied to join the Toronto Police Service in 2019, he failed the background check administered by the Toronto Police Service Board (TPSB).

Interestingly, he passed a TPSB background check in 2018 for work as a Special Constable with the Toronto Community Housing Corporation. What changed in that year? He submitted access to information requests and repeatedly asked for reasons, but he was denied, so he sued.

The Appeal

Public decision-making bodies that are not courts commonly make decisions on behalf of the government. School boards, transportation authorities, the Canada Revenue Agency, land tribunals, and the TPSB are all examples. Decisions these bodies make that resemble court decisions can be appealed. If the body doesn’t have its own review system, the case can usually be appealed to the court. Appealing a public body decision to the court is called “judicial review.”

That’s what Mr. Khorsand did: after exhausting his other options, he appealed the TPSB decision to fail his background check. It went before a three-judge panel of the Divisional Court of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

The Law: Procedural Fairness

In some cases, a statute will outline the specific procedures to follow when making or appealing a decision. Where the law is silent on specific procedures, there is still a minimal right to have the procedure be fair. This usually means being able to make your case before the decision-maker, and in some cases, means there is a duty to provide reasons for the decision. As the Supreme Court of Canada said in Nicholson v. Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Police Commissioners, [1979] 1 S.C.R. 311, individuals who are the subject of a public body decision “should be treated fairly, not arbitrarily.”

The Arguments

Mr. Khorsand’s lawyer argued before the Divisional Court that not receiving reasons violated TPSB’s minimal duty to make decisions like this fairly. The decision was important not only to Mr. Khorsand and his career but also relevant to the public: the public has a valid interest in knowing that the police make hiring decisions fairly and not arbitrarily or discriminatorily. To this end, they must give reasons for failing a background check.

The TPSB responded by saying that, among other things,

- It cannot disclose information received from other police services or agencies

- Some of the information may contain highly confidential and sensitive information about third parties

- Disclosing some or all the information can compromise law enforcement techniques and procedures and can put people like undercover informants or third parties from whom information is received at risk

- Reasons might expose how the background checks are conducted, which could make it easier for people to figure out how to fake the information that law enforcement reviews

The TPSB also argued that this was not the kind of decision that could even be subject to judicial review. Instead, it is simply an employment matter. TPSB relied on the fact that Ontario courts have said in the past that hiring staff is an example of an internal, administrative matter which cannot be judicially reviewed.

The Outcome

The Divisional Court ruled 2-1 in favour of Mr. Khormand. The majority found that the decision was a valid subject of judicial review due to the “public character” of such a decision. It also found that the TPSB violated the minimal duty of procedural fairness it owed to Mr. Khorsand. The Court held that TPSB’s duty required it to do two things: (1) give Mr. Khorsand the reasons he failed his background check and copies of the information leading to the decision, subject to a process to protect sensitive information, and (2) allow Mr. Khorsand to dispute those reasons and information.

The judges ruling in favour said that police officers are held to a high standard by the public to be unbiased in their policing, measured and patient in dealings with the public, and have good character. While the public expects government workers to generally be competent and do good work, the public’s expectations of police officers are clearly very different from typical office staff like an office assistant. While one cannot judicially review every hiring decision, it is reasonable to suggest that a police officer is in a unique position; the public has a valid interest in knowing that police officers are being chosen fairly and not arbitrarily or discriminatorily.

They also said that information provided to the individual should be appropriately redacted to avoid breaching confidentiality.

Where do we go from here?

The Divisional Court's decision is currently being appealed to the Ontario Court of Appeal, which will take months or years to resolve. The decision may even find its way before the Supreme Court of Canada one day, meaning the ultimate resolution would be years away.

Unfortunately for Mr. Khorsand, his life cannot stand still while he waits for this case to be resolved. It has been five years since the TPSB told him he failed his background check. He has had to find new work and perhaps a new field altogether. If he wins the case and appeals are finally exhausted, then he will only receive reasons, with the TPSB getting to control how much to redact without oversight. In its own interest, it will likely redact very generously, which raises its own issues. Mr. Khorsand may have the opportunity to appeal the reasoning, but whether he decides to do so will be an open question. It might be eight years after the decision is made, and at that point, will he want to abandon his current career to go back to pursuing his dream of joining law enforcement?

What Mr. Khorsand will do once the dust settles on this litigation is unclear. However, the hope is that his work with this litigation, and that of groups who have submitted arguments, such as the Black Legal Action Centre and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, is not in vain.

The hope is that the next time someone is rejected from employment as a police officer due to failing a background check, they will quickly be able to read the reasons, to ensure they are fair. They will promptly be able to appeal that reasoning to ensure that it is defensible and proper. That we, the public, will be able to know that the decisions made in hiring our police officers are just and proper—every time.