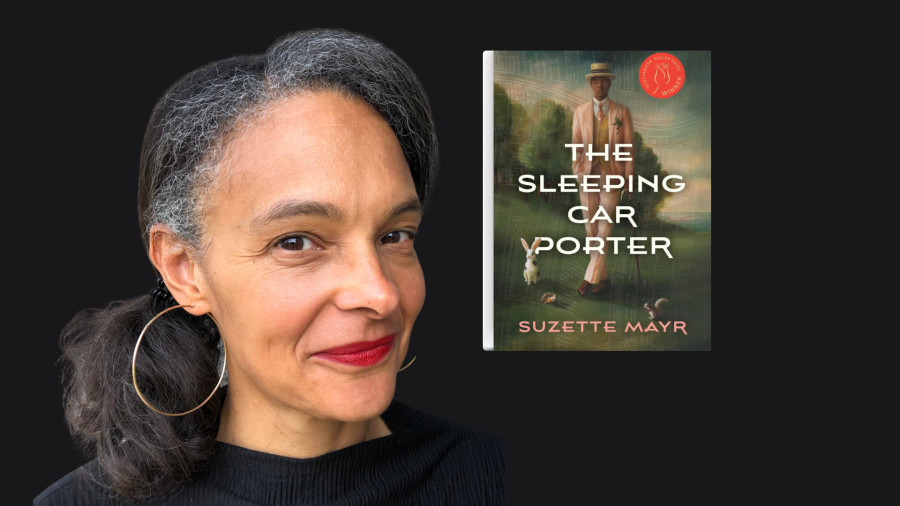

Mayr, a Black biracial lesbian of Afro-Caribbean and German descent, who teaches creative writing at the University of Calgary, won the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize, valued at $100,000, and she deserved it.

The Sleeping Car Porter follows Baxter, an aspiring dentist and gay twenty-something Pullman Porter, on a railway voyage, from Toronto to Vancouver. Following life through the organized tasks of one of the few respectable jobs available to Black men in the 1900s, reading this novel reminded me of my proximity and love of railway travel, my retired father's work as a train machinist, and my 2019 trip on the famed Canadian that spanned four days.

Mayr's book aptly covers the monotony, the wonders of nature, the conversations with strangers, the ever-changing nature of arrival times, the luxury, and the Canadian racism–all in simple, concise prose.

What was your inspiration for writing this novel?

My decision to write the novel resulted from a challenge posed by one of my former writing teachers, the poet Fred Wah. One day more than 20 years ago, he told me, “Suzette, you have to write about the porters!” I didn’t know what he was talking about, and I didn’t know what history he was referring to.

So, I started doing some research into sleeping-car porters in Canada, and I learned that they were almost all Black men; that portering was perhaps the best-paid job a Black man in Canada could get, but they regularly faced terrible prejudice; that porters had a crucial role in labour and civil rights in Canada; and that some porters were either the fathers of famous Canadians like pianist Oscar Peterson or they went on to become prominent people in their own right, like Rufus Rockhead of Rockhead’s Paradise and Stanley G. Grizzle.

Writing the book was also about finding an unrecoverable, lost or deliberately hidden history that I desperately wanted or maybe even needed. I’m writing about a gay, Black man in the 1920s who worked on a train during a time when queerness in Canada was punishable by prison or worse and a time of intense anti-Black racism. There are no records beyond sketchy criminal court records of how someone like my main character might have lived or felt, but to understand myself as a Black, queer person, I needed to “find” those records to understand my place and who I am. My need to find an ancestor – to find Black, queer family – kept me going through the process of writing this book.

The novel is organized by days, in a series of moments, and even lists a sleeping car porter’s tasks. What was your intention in doing this?

What struck me when I was doing the research for this book was how regimented the work of a sleeping car porter was. In the historical period I was most interested in, the porters had to follow the rules outlined in these little instruction handbooks, and the rules seemed to cover everything. For example, how to address a passenger, times of day when certain work obligations had to be carried out, and when not to lock the door to the lavatory.

Of course, the subtext of those handbooks is that a porter could be fired for pretty much anything, even for things beyond his control. The main character Baxter in the novel, desperately needs his job and doesn’t want to lose it under any circumstances, so he tries to live by the rules outlined in the book.

The problem though is that his job is impossible: there’s no time to sleep, the food is terrible, and even fraternizing with work colleagues is frowned upon, so where is there room for even a little bit of joy?

Baxter is trying to make this impossible situation work. He has to think very carefully about every action he takes and every job he does, but the job is boring, demeaning, and sometimes nonsensical. I wanted the reader to understand the grinding monotony and impossibility of the job, so I went into a lot of detail about these elements.

Race is rarely mentioned, but it is implied, especially about the class position of Baxter and the other sleeping car porters. Was this an intentional decision?

Yes, this was intentional. I know that as a Black person in the world, I am constantly aware of race, but at the same time, I’m still living my private life, and there are a lot of aspects of my life that don’t have to do with race or where race rarely comes up.

While I think about race or am reminded about my race a lot, I also have other issues I need to consider, like, what will I cook for dinner tonight? Whose turn is it to walk the dog? It was vital for me to get into the head of the main character and see him as a whole person for whom race is essential and who is definitely racialized by the world, but who – for example – also thinks about things like what he likes to eat and read, what his body needs sexually, and his love for his Aunt Arimenta. Race is important, but it’s never all a person is – it’s not how a person should be exclusively defined.

I got the sense that sleeping car porters were a brotherhood. What important message do you think that brotherhood has to share with us today?

They worked so hard, and weren’t paid enough or respected enough as people to do that kind of work. And the work was impossible. The porters were vital in that they had a vision for how Black people should be treated – as workers, as citizens, and as Canadians.

Writing The Sleeping Car Porter took a tremendous amount of research. I enjoyed listening to you describe the years and details of your study– grants, archives, books, interviews, newspaper clippings, and trusted readers. How did you make decisions about what to include in your novel?

In the end it came down to trusted friends of mine who are writers and editors, reading the manuscript and telling me what was important and what was extraneous.

In the penultimate draft, I think I cut out at least 40 pages, and this was the right choice because the majority of those pages were just more repetition of the main character Baxter at work on the train polishing more shoes and dealing with more annoying passengers who took up a lot of space. In the end, those passengers didn’t make the cut.

For example, there was a passenger who gave herself an abortion that went very wrong. I liked that scene very much, but in the end, neither the abortion nor the passenger added anything to the book, and they just veered the book into a direction that went nowhere.

Where were you when you received the news about your book winning the Scotiabank Giller Prize? And how did you feel?

I was at the gala dinner, which was being televised on the CBC. When I heard my name, I suddenly wanted to cry – I think mostly from shock. I never thought I would win the prize. But I knew I was on national television, and I couldn’t just sit there bawling and processing my feelings about why I was bawling. I couldn’t understand what was going on, truly. I was electrified that the book had won, but I was also sad because I really loved the other shortlisted writers, and had come to love them as my friends, and I wished their books could have won too.

Who do you read for inspiration in your writing? Is there one Black Canadian writer who inspires you?

Lately, I’ve been loving Bertrand Bickersteth’s book of poetry, The Response of Weeds: A Misplacement of Black Poetry on the Prairies. It deals with the Canadian prairies as a geographical and historical setting, but it touches on the work of so many other important and exciting Black writers such as Langston Hughes. It’s a gorgeous book.

Also, Cheryl Foggo is a historian and fiction writer from Calgary, and her non-fiction book Pourin’ Down Rain: A Black Woman Claims Her Place in the Canadian West was huge for me. I was working at the small, independent press that originally published it about 30 years ago, and I remember reading it at work and being floored by the fact that it was the first time I had read about Black people on the Canadian prairies.

New Releases by Black Canadian Creators

Little Black Lives Matter by Khodi Dill

Illustrations by Chelsea Charles

(Triangle Square/Penguin Random House Canada)

Released: January 10, 2023

The Enchanted Bridge by Zetta Elliott

Illustrated by Cherise Harris

(Random House Books for Young Readers)

Released: January 17, 2023

The Hockey Jersey by Jael Richardson with Eva Perron

Illustrations by Chelsea Charles

(HarperCollins Canada)

Released: January 17, 2023

In the Upper Country by Kai Thomas

(Viking)

Released: January 10, 2023

Beyond These Eyes by Faith Tull

(Africa World Press)

Released: January 23, 2023

By

By