Like all authors, I have high hopes for my book. One of these hopes, secretly, is to find an ancestor– my maternal grandfather.

Like many of my relatives and Jamaicans over generations, both of my grandfathers migrated, as young men, for work. In the 1950s for several months at a time, GH and DP did “farm work” in the United States, much like the seasonal agricultural worker program (SWAP) in Canada. Each year, they would return home to Jamaica to support their families. I grew up to know my paternal grandfather, GH, who lived to his eighties. He was able to immigrate permanently to the US through a special program after working on farms for several years. My maternal grandfather, DP, passed away while in the US in his twenties.

The story surrounding his death has always been hazy, having changed slightly over the years, from how he died to where he spent his final hour. At the time, my mother was a toddler, without clear memories of him, not even a photo.

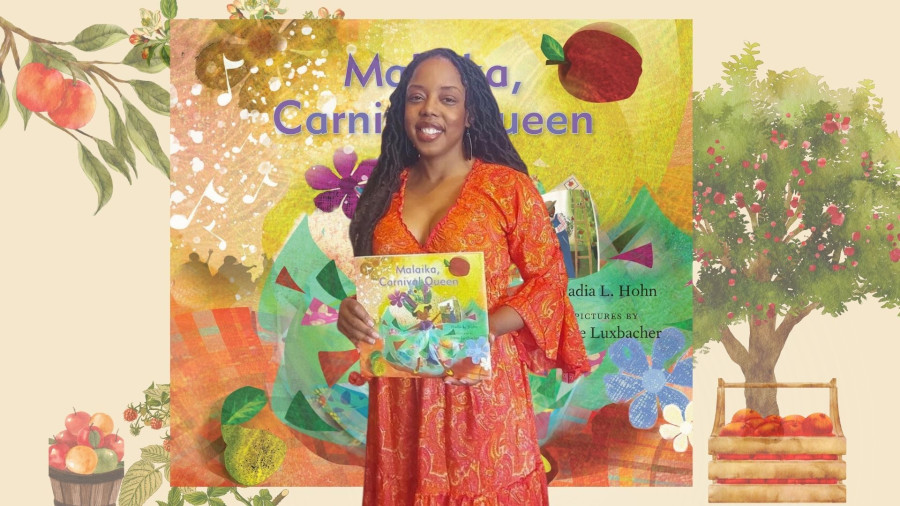

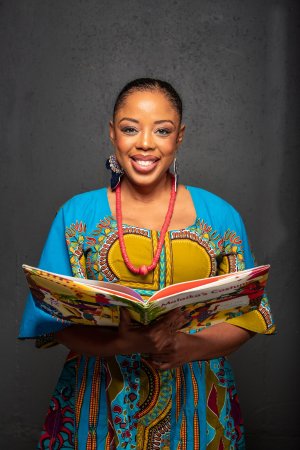

I am an author of books for young people whose work celebrates diversity and represents characters on the page. Carnival has long occupied my imagination. When I was asked to write a picture book manuscript for an assignment at a George Brown College continuing education class in 2010, I knew immediately what mine would be about.

For the first time at about age seven, my father took my sister and me as children to watch the Caribana parade on University Avenue. One of my first illustrated books, written at the age of ten, was called The Greatest Carnival Ever. As a teen, I began to go on my own to Caribana. As a thirty-something, I began to play mas’ in what is now called the Toronto Caribbean Carnival and eventually at Crop Over in Barbados.

My writing assignment would eventually become Malaika’s Costume, my first picture book published in 2016. The story: It’s Carnival time, the first Carnival since Malaika’s mother left to go to Canada to work. But, when the money that she said she would send to make her costume doesn't arrive, Malaika wants to find a way to be a part of the kiddie Carnival parade.

As I focussed on telling this story, other things emerged. My attempt to create a pan-Caribbean tale in a “nondescript pan-Caribbean anglophone country”, resembled the setting of my mother’s childhood home in a rural Jamaican village. Many of the Carnival references were influenced by Trinidad. The resulting story was of a Caribbean immigration experience told in a blend of English and Caribbean patois. The family separation with the mother away in Canada, the “barrel child” in Malaika, the intergenerational relationships with a grandparent as primary caregiver, the community pooling together resources to help its young people, the financial needs and dollars from abroad helping family at home, the loss and absence of a mother– these were all experiences, stories of my family’s immigration and migration and those of many of my Caribbean friends and colleagues. When had I seen these topics covered in a picture book? Where was the literature about the impact on future generations? Certainly not in my childhood years of growing up in 1970s/1980s/1990s Toronto and so representation in my stories is key.

After publication, Malaika’s Costume resonated with many. My book was granted an Americas Award Honour in 2017. Off to Washington, DC I went to receive this honour at the Library of Congress. In 2021, Malaika’s Costume was the TD Grade One Book Giveaway, given to first graders, over 550,000 copies across Canada. It was the first book by a Black author to be selected for this honour as well as the first in the giveaway to be turned into a float for the 2021 Original Santa Claus Parade. I was approached by a number of individuals from Guyana, Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad, and other places who told me that Malaika’s immigration story was their story. They too lived with their grandmothers while their parents went abroad to work.

I have presented Malaika's Costume to audiences around the world. When at schools, I commonly ask my young audiences to define carnival. Many of my non-Black students mention rides, costumes, music, and an amusement park. But for a child in the Caribbean diaspora, Carnival has a special significance. Carnival is resistance, a way to reclaim our African-Caribbean practices, a means to take up space in our respective diasporas. Carnival is seasonal– taking place before Lent in Trinidad, Cropover in Barbados, Labour Day weekend in Brooklyn, late August in Notting Hill, after Christmas Junkanoo in Jamaica and the Bahamas, and many others. For us in Canada, our elders brought Carnival to their new home. Caribana, Carifiesta, Carifête are some of the many Caribbean festivals spread throughout this land– large scale re-creations of the holidays they celebrated back home.

As the months led up to the publication of Malaika’s Costume, I began to wonder and ask more questions about my lead character. I began to think about uniting Malaika with her mother in Quebec City. After spending a lot of time in the province for work, study, and love in my twenties, Quebec was a setting I felt could offer a lot of contrasts to my character as many immigrants experience in Canada. Through the changes in climate, language, a French Canadian stepfamily, and a new Carnival, Malaika’s Winter Carnival was released in 2017. Malaika’s Surprise followed in 2021, inspired by the birth of my youngest sister and a response to the Quebec mosque attack in 2017.

Continuing a thread of father and daughter relationships started in Malaika’s Surprise, for Malaika, Carnival Queen, not only was I inspired by my grandfathers to whom the book is dedicated, I was also inspired by a dream I had. In it, I saw relatives– ones I recognized and one I didn’t.

When I awoke, I described the dream to my mother. Having parents from Jamaica, I knew about the significance dreams hold. After I described it, she told me this mystery person was my great-grandmother. I found it a little creepy that I could dream of someone I hadn’t met before. From what I’ve learned about blood memory— we have connections with those who came before us at a cellular level, whether we are aware or not. And so, Malaika, Carnival Queen starts with a dream inspired by my own.

After I had written the story and sent the manuscript off to my publisher, I decided that I needed to see and understand the world that my grandfathers inhabited. I wanted to visit migrant farm workers in Ontario, to meet them face to face and hear their stories.

My journeys to the farms and the organizations that support them felt clandestine from the start. Someone I had met at a social event had worked with migrant workers and gave me a list. I made calls and the first farms turned me down but, eventually, I made some connections. At a large farm, I met Black Caribbean men who had been working there for 25+ years, and had adult children working there as well. These were the men and women who had created a culture and a new family with each other– friendships, parties, worship services, soccer games, and cars.

At another location, I met Black Caribbean men, sitting in a circle, with bottles of beer and cigarettes between them, their voices and expressions low. When I asked if they wanted their children to do this work, one man chuckled stiffly and said it was slavery. I was told that their living conditions were crowded and after a long period of discomfort, a sewage pipe in their quarters was finally fixed. I sensed their isolation with vast fields of ripening fruit, waiting to be picked. I visited an outreach centre and attended a gospel concert for migrant workers. I learned so much. All the while, I wondered, why was I never taught more about these predominantly Caribbean communities, especially given the pivotal roles they play in our Canadian food chain? I invited my illustrator to accompany me on another trip to visit workers, so she could have more references for our book.

These visits, my dream and the story of my grandfathers, blended with family history, manifest in Malaika, Carnival Queen. In it, Malaika navigates grief, loss, and legacy, while holding onto her Caribbean patois, family, community, and love of soca, and Carnival. She continues to adjust and embrace her life and family in Canada– lived realities that are part of us in the Caribbean diaspora, especially for me as a second-generation Jamaican-Canadian as I try to revive the memories of my elders— grandfather DP and other relatives – without photos. My diasporic longing is strong.

A rare occasion is when a new detail arises, bringing the picture of my grandfather into focus. Most recently, I received names and copies of photos of my DP’s mother and sister, as well as the US city in which they lived.

And so my journey as a writer continues.

New book releases by Black authors this month:

Malaika Carnival Queen by Nadia L. Hohn (Groundwood Books, May 2)

The Private ApartmentsThe Private Apartments by Idman Nur Omar (House of Anansi, May 2)

Sargasso Sea Scrolls by Dannabang Kuwabong (Mawenzi House Publishers Ltd., May 18)

I Am Big by Itah Sadu, illustrated by Marley Berot (Second Story Press, May 2)

By

By