Some events have already happened, others are upcoming, and Toronto has been central in recognizing her 100th birthday with activities at the Harboufront Centre, York University, Toronto Reference Library and A Different Booklist Cultural Centre: The People’s Residence.

Bennett-Coverley was born on September 7, 1919 in Kingston, Jamaica and lived in Gordon Town, St. Andrew; London, UK; New York and Florida, U.S.; and here in Toronto, Canada where she resided for almost 20 years and died on July 26, 2006.

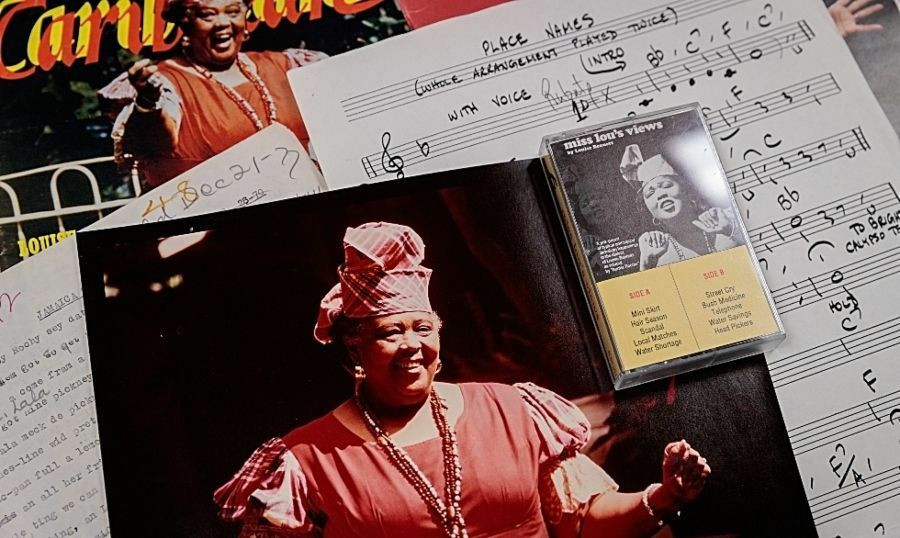

McMaster University Library houses the Miss Lou Archives, which contains correspondence, published and printed materials, personal and professional documents, awards, photographs, and more from Miss Lou’s life in Canada.

“Miss Lou’s Room,” a multi-purpose space which is the home of an exhibit honouring Miss Lou and her achievements, is at the Harbourfront Centre. It features photographs and recordings of her storytelling and many performances, and is heavily used for children's programs.

In Jamaica, the Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport; University of the West Indies Institute for Gender and Development Studies, National Library of Jamaica, and Jamaica Cultural Development Commission have organized the “Miss Lou’s Centenary Celebration” from September 1 to December 10, Human Rights Day.

While most of the events are happening there the schedule includes activities in Canada and in the United States.

Miss Lou was Jamaica’s cultural ambassador at large, a champion of the Jamaican Language, a poet, author, actor, educator, folklorist and cultural activist.

Fittingly, when a statue of her was unveiled in her hometown of Gordon Town, St. Andrew last year to mark her 99th birthday, members of the Jamaican Canadian Association started making plans to be there this year for the 100th commemoration.

A contingent of 55 Jamaican Canadians flew to Jamaica where they attended a civic ceremony to celebrate the centenary of the birth of Louise Bennett-Coverley at Gordon Town Square on September 8. It was announced that Gordon Town Sqaure would be renamed in honour of Miss Lou.

On September 6, the University of the West Indies in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport presented “Miss Lou’s Labrish,” a pre-birthday celebration that involved several academics, including Professor Opal Palmer Adisa, university director of the Institute for Gender and Development Studies.

She is the coordinator of an anthology featuring 100 voices in honour of Miss Lou’s 100th birthday anniversary which is scheduled to be presented to the government of Jamaica on December 10.

It was an evening of cultural performances and tributes by artists such as the legendary dub poets, Jean Binta Breeze and Mutabaruka; Djembe-Kon Drummers, Frankie Campbell and Grub Cooper of the Fab Five Band, Barbara Gloudon, Dr. Carolyn Cooper, Dr. Amina Blackwood-Meeks, and others.

Miss Lou was lionized as an intellectual activist, a philosopher of culture, a cultural leader with a postcolonial perspective, and according to Olivia Grange, minister of culture, gender, entertainment and sport – “Miss Lou liberated the people’s language and through that the people themselves.”

Co-executor of Miss Lou’s estate, Fabian Coverley said he knew her as his mother and called her Aunt Louise. He noted that Miss Lou was very religious and that he has plans to publish a book on the anniversary of her 101st birthday.

“Miss Lou was a citizen of the world whose contemporary cultural criticism was wrapped in the guise of humour,” said Pamela Appelt, also a co-executor of the estate.

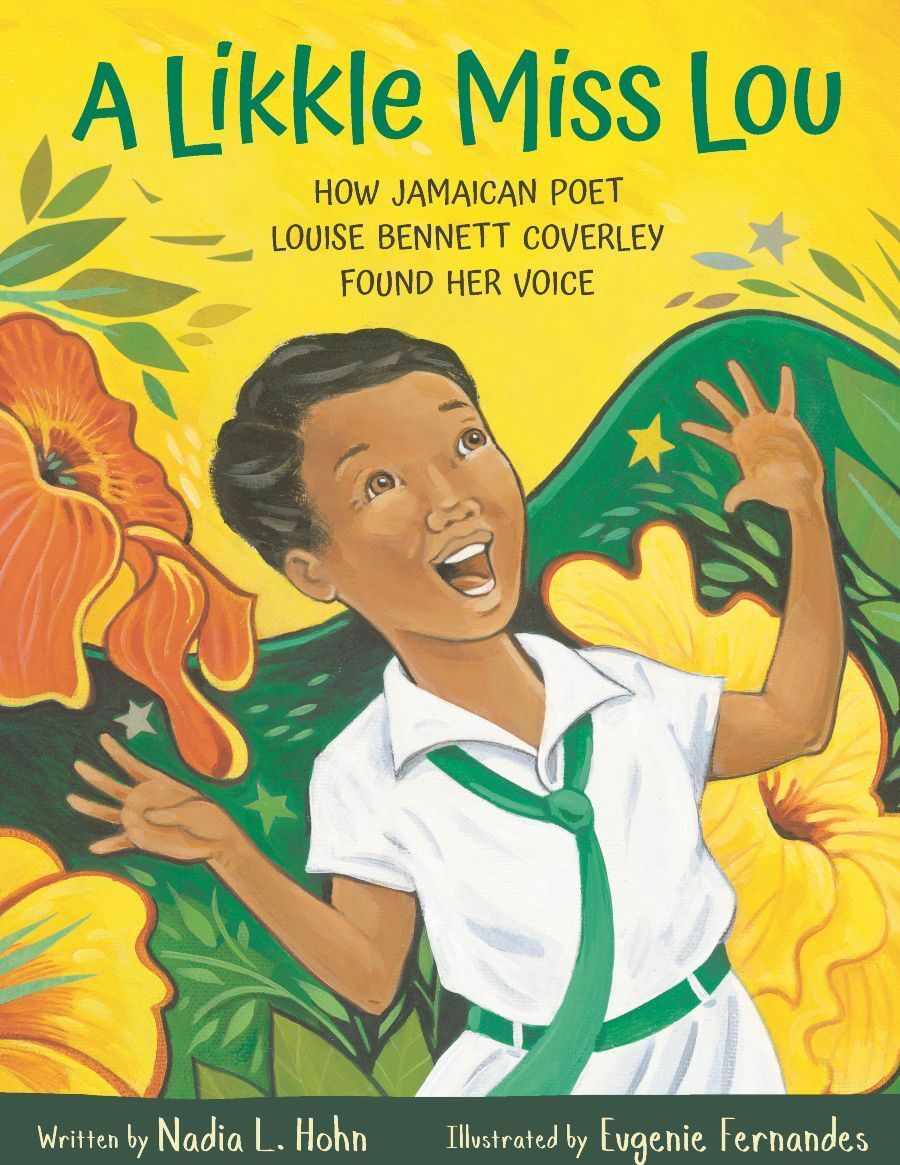

Among the Jamaican-Canadians who travelled from here to Jamaica was Nadia L. Hohn whose new children’s picture book, A Likkle Miss Lou: How Jamaican Poet Louise Bennett Coverley Found Her Voice, was launched at A Different Booklist Cultural Centre on September 14, two days after she returned to Toronto.

It took her seven years to write the book which is illustrated by Eugenie Fernandes. A Likke Miss Lou is inspired by the early years of Miss Lou and is “brought to life in a sun-drenched palette,” telling “a story of Miss Lou’s beginnings as a girl who just wanted to be heard in the language she loved.”

Hohn said she decided to write about Bennett-Coverley because she knew that there wasn’t much about her life that is published.

“As a teacher I knew the importance of her work, especially to a younger generation, because there is nothing really there. So, I kind of wrote it knowing about the absence of the information but also as a part of my project,” says Hohn who was at the time enrolled in a writing class at George Brown College in Toronto.

While developing her idea she attended a workshop on writing biography for children where she was told “if you can write your book in a significant year of the person’s life or significant time try to do that.”

Hohn went on Wikipedia and realized that Miss Lou’s birth year was 1919 and that the 100th anniversary was approaching.

“Without knowing what was going to happen I just knew that I needed to put all my energy in getting this book ready so that it can be submitted.”

She said typically it takes three years for a book to get to publication, especially a picture book, so in the fall of 2017 she approached various publishers but they couldn’t guarantee that it would be ready by 2019.

Hohn eventually found Owlkids Books, a publisher that was interested and that promised to get it ready by 2019.

The creative process went quicker than any project that she has worked on. The book was out in August, one month before Miss Lou’s centenary celebration..

Hohn is now thinking of writing a second book about Miss Lou – not a picture book but a novel for young people.

She was ecstatic to be in Jamaica for the Miss Lou 100th celebration. “It’s a moment in history that was so significant. I knew that I needed to make sure that I was going to be there.”

In the 1970s Miss Lou performed to capacity crowds in the Toronto Public Library’s Parkdale branch. Honor Ford-Smith, a scholar, poet and playwright, says no other performer before Bob Marley was as loved by Jamaicans of all classes and race than Louise Bennett.

“Though most people have a general sense of her as a performer who advocated for the Jamaican language and culture few are aware of the breadth of her contribution and the context within which she worked,” Ford-Smith said while speaking about Bennett’s achievements in the context of her time.

She said Miss Lou came to voice in the context of worldwide anti-colonial resistance, the most vibrant and varied social movement of the last century. When Bennett was born in 1919 European colonial powers directly controlled about eighty percent of the globe.

“That this is no longer the case has to with the achievements of the social movements with which her life and work intersected. Bennett’s work overlapped with several generations of men who are far better known nationally than she is for their critique of the ideas and practices that underpinned the colonial regime.”

“Never a sterile spectator she insisted on breaking the barriers between spectator and participants in a search for a social progress and a social unity in a deeply divided island. Her words pick sense out of the nonsense of calamity to reveal a sea of vibrant possibility created by the people that she loved.”

The professor said Bennett’s work was part of the process of voicing the intellectual and cultural ideas of the Caribbean. She noted that the difference between Bennett and men like CLR James, Césaire and others was that she was a woman and one of the only black women of her generation and race to come to visible and popular voice in the context of the anti-colonial struggle.

Ford-Smith noted that unlike Césaire and James she chose to speak from the position of a working class peasant woman and to speak in the language that they spoke. She was neither working class nor peasant but that was what her persona became.

The professor said Bennett was supported by two significant developments which are often forgotten in describing her trajectory. First, she was supported by a popular performance tradition which was considered in its time quite vulgar and which had developed a significant following by the 1930s.

She noted that Miss Lou’s early career was supported by the women’s movement of the time. Black feminists like Amy Bailey, Mary Morris Knibb and Madame de Mena Aiken of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) had fought for women’s political rights. This movement became subsumed into the Jamaica Federation of Women for whom Bennett worked as a kind of cultural animator.

Senior, a poet and author, said the early decision by Bennett to give voice to the ordinary people of Jamaica was one that she boldly defended.

“In the process Miss Lou opened the gates for not only a long list of spoken word artists and performers but was also a profound influence in freeing up the so-called literary heavyweights from the straightjacket of conformity. Miss Lou did not say we must throw out or disrespect the English language, what she affirmed was that we should also claim respect for our own language alongside our inherited English tongue.”

Senior said this opened the gateway for writers such as herself who was struggling to find “our own voices, one that would allow us to be true to ourselves and to the culture we come from while writing our way into a global culture.”

She said Miss Lou must not be seen as simply an icon for that is no more than a picture, a surface representation of a revered person.

“Perhaps then the conversation should be about Miss Lou as a national hero, not a hero of deeds but of words, words that are mightier than the sword.”

Neil Armstrong is a Toronto-based journalist who freelances with the Jamaican Weekly Gleaner and formerly with Pride News Magazine, and Caribbean Headline News on Rogers TV. Previously, he worked at Radio Jamaica Ltd.(RJR), CHRY 105.5 FM (now VIBE FM) and CJRT FM (now Jazz FM).

Is there a Black Canadian story we should cover? Email us at info (at) byblacks.com.

By

By