Award-winning actor, director, and artistic director of Obsidian Theatre, Philip Akin, directs playwright Antoinette Nwandu’s Pass Over at Toronto’s Buddies in Bad Times Theatre. Pass Over is a layered contemporary play about race, class and power. It appears to be loosely based on Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, about a pair of homeless men named Vladimir and Estragon, waiting aimlessly for days on end for a mysterious person named Godot.

In Pass Over, these two protagonists are replaced by Moses and Kitch, acted comically, and at times tragically, by Kaleb Alexander and Mazin Elsadig. Moses and Kitch aren’t waiting for a person, so much as freedom from their everyday cycle of hopelessness and abuse at the hands of Ossifer; a villainous, brutalist police officer. They long for a destination called the promised land; a safe space outside of their block that seems daunting to reach. Throughout the play, you'll notice many representations of socio-economic barriers thrown up to keep members of marginalized classes in cycles of poverty and powerlessness.

The appearance of a relatively benign Mister, perhaps the most stereotypical trope of whiteness I’ve seen in a while, references power imbalance through his initial “mistaken” introduction to the protagonists as Master. He offers to share a lunch he’s prepared for his sick mother after getting lost in their neighbourhood, and leaves a pie behind for Moses and Kitch. This could be a riff on White liberal guilt, or even perhaps, gentrification. Regardless, this metaphorical pie goes missing soon afterward when Ossifer takes their “piece of the pie” away from them. Both Ossifer and Mister are played by the same actor (Alex McCooeye) as two heads of the same oppressive coin, which is intentional.

Throughout the play, Moses and Kitch greet each other with the call and response “kill me now” which is followed by the response “bang, bang.” Is this about the disproportionate threat of violent police encounters resulting in death for Black people that flood our media on a consistent basis? Is it a comment on the hopelessness of people who feel trapped in inescapable cycles of poverty and trauma? Could it be about “Black on Black crime?” In truth, it could be about all of those things, which is an example of how art can mean different things to different people, while still being grounded in a common truth. The truth, or truths, brought up in Pass Over are universal and timeless.

Perhaps that’s why it was so easily adapted from Samuel Beckett’s play, which was written in the late 1940’s. The have-nots in every society, in every moment in history, have always been boxed into ghettos. They have always been told their place, or put in their place, by law enforcement acting as agents of the state. They’ve always had the bar moved a few inches higher every time they got a bit too close to reaching it. The very idea of a “promised land” is taken from a 2000-year-old story in the bible, about the exodus of a group of people placed under bondage by another. Similar to the Moses of that book, Moses in the play has dreams (or visions) of a different life outside of his neighbourhood, and he and Kitch make every day about making the dream a reality. But is desire really enough to overcome the tangible and intangible systemic obstacles placed before them?

The question is eventually answered in an unforeseen, yet definitive way. The audience is left to ponder how this plays out in the real world. What does it mean for people living through less exaggerated, but no less difficult, realities. Pass Over is a play that deconstructs class and race in North America through allegory and metaphor. Moses and Kitch, though representing the hope of the American dream, are also forcefully kept away from the promise of it. The duality of force is represented by both police (state violence) and citizen (whiteness/White liberalism), and the fate of Moses and Kitch is not much different regardless of which force they’re dealing with. One form of violence enforces a division, while the other, seemingly less threatening, both enables and is protected by the first. By the end of the play, it becomes questionable which form of violence is actually worse.

Black Toronto, please don’t “pass” on Pass Over. It’s a must-see play, written by a Black playwright, and produced by a Black Canadian theatre company (Obsidian), that speaks to issues affecting the diaspora right now.

*Reviews are rated out of 5 B's

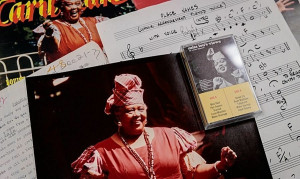

All photography by: Cesar Ghisilieri

Pass Over

Buddies in Bad Times Theatre

12 Alexander Street, Toronto M4Y 1B4

Playing Oct 22nd - Nov 10th

Byron Armstrong is a writer living in Toronto who has been published online and in print, for both local and national publications. He writes essays, short stories, opinion pieces, and in depth interviews. His general musings can be found on Twitter as @ByronArmstrong6

By

By