Humans as food for a system that will devour their labour, culture, and children — even the whole of the earth itself — and still, its hunger will not be sated. Nigerian-Canadian multidisciplinary artist Oluseye Ogunlesi is challenging Canadians to wrestle with this history of violence and our, up until very recently, obscured history relating to slavery with his installation for Luminato. Black Ark is a monolithic twelve-foot-tall reimagining of the hull of a slave ship that has landed on Ashbridges Bay Park like, to quote Malcolm X, “Plymouth Rock landed on us.”

But this isn’t really about the U.S. Instead, this work is based on little-known facts about our multicultural haven utopia that were passed on to Ogunlesi on Canada’s east coast while staying in North Preston, N.S.

“An elder named Pastor Al told me how some of his ancestors decided in 1792 to take the trip to Freetown, Sierra Leone, to start a new life. This resonated with me because I didn’t know that Black Canadians left to help start this new African nation,” Ogunlesi explains over a Zoom call. “I also learned that over sixty slave ships were built on Canada’s east coast.”

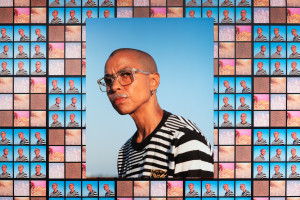

Ogunlesi considered how to connect and embody these intersecting bits of ancestral knowledge in a structure that acknowledged those histories. This initial thought sparked the construction of his largest artistic work to date. Seated next to Ogunlesi on the call is architect Toluwalase Rufai, a recent Howard University alumni and an essential collaborator for the project. Some people think artists are lazy and creative work is easy. Ask any Black creative in this country who has fought to be paid what their work is worth if you don’t believe me. However, observing this pair of exhausted-looking Black creatives one day after revealing their installation proves the opposite. Both are seated in an alabaster studio, the background adorned with mysterious onyx materials, all of which create a contrast on the wall that could be a singular work of art on its own.

“The project came in phases,” says Rufai of the path to the exhibition. “The original ideation was about a three-month back and forth process, the design took another three months, and the actual building took a few weeks.”

“The idea came before the opportunities to apply for funding, then you have to factor in grant applications to secure funding,” adds Ogunlesi. “The first time we tried to get it done through one of the City of Toronto’s projects, we didn’t get that bid, then we tried the next year with ArtworxTO and were successful. It’s been a long process going back to 2020.”

2020. The year of COVID, economic instability, and chants of “Black Lives Matter” taking over the globe. In 2022, you can add war and food shortages to that list, as the rest hasn’t appeared to change all that much. However, one thing that did seem to happen is the city and arts institutions finally cracked open their conservative Wasp-y wallets for Black artists in Toronto.

“I think that many institutions and funding bodies realized there was a gap in our cultural systems, and there was a realization that they had to do better,” says Ogunlesi. A lot of things picked up for me in my career after that. When you think about the proportion of Black people and that most galleries didn’t even represent a black artist—some of that has gotten better since the loss of George Floyd—so, in many ways, we have a lot to thank him for.”

Ogunlesi and Rufai have been friends since 2015 after meeting over Instagram. Ogunlesi had been following Rufai’s posted work on the app and thought that if he ever had the chance to build something at the skill and scale that he wanted, Rufai would be the person to reach out to. Ogunlesi’s past sculptural work employs materials that speak directly to the meaning behind the work. For example, “Ploughing Liberty” fuses discarded hockey sticks with antique farm equipment to discuss The Black Loyalists and questions about whose labour is respected. In “Demilade,” Ogunlesi employs elements of what I’ll call “Africana”—the antithesis of Canadiana—cowrie shells and synthetic hair. As such, I wanted to know what materials were used in “Black Art” that might speak to the work’s deeper meaning?

“The interior is a polished, reflective metal so that you can see your reflection,” Ogunlesi explained. “One of the things Europeans brought with them to barter with African kidnappers for enslaved people was mirrors, so I was thinking about how, at one point in time, the value of Black life was a mirror. How big was that mirror, or how many mirrors did it take to get one or several strong Africans?”

The ship's reflective interior acknowledges that history and forces the viewer to physically engage with the history represented.

“As the viewer approaches the structure, whether they choose to enter the structure or not, their reflection will be caught in it,” says Ogunlesi. “Depending on who you are in Canada, it also looks at who is complicit and implicated in the legacy of slavery. All of us, regardless of race, by virtue of being here, benefit from the labour of enslaved people.”

To see yourself fully, you must know yourself. What do several generations of slavery, segregation, forced integration, and assimilation do to a person?

“Conceptually, the fragmentation of reflections represents the dissociation of a human being's knowledge of who they are,” Rufai adds, answering my question before I have the chance to ask it. “The further you walk toward and into the sculpture, the more your reflection is broken into multiple pieces. It mimics the feeling of losing your sense of identity walking through the piece and references how an enslaved person would lose their identity as they were taken away from their land, people and culture.”

The other material used in the Black Ark is burnt wood.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce7GeibLPSO/?hl=en}

“I was living in the Ivory Coast last year, and there was a technique where some of the homes on the beaches were wood stained with sediment from diesel,” says Ogunlesi. “It created a beautiful patina that would fade over time, so they had to reapply the diesel.”

Ogunlesi thought the process was an organic way of achieving a patina on Black Ark, which, up close, almost reflects light off its outer surface. As opposed to burning diesel, however, they instead burned the wood.

“To burn wood as an aesthetic kind of involves destroying the surface of the wood and, symbolically, was like burning Black history into Canadian history so that it becomes recognized as such,” Ogunlesi says. “As I was burning the piece, I also thought about some of the revolts that happened on the slave ships and how, in the quest for one’s freedom, enslaved people were fully prepared to burn the whole thing down. It speaks to the human quest for survival and the idea of risking death to survive.”

Risking death to survive is a contradiction that every Black person understands. You could be stopped by police on the way to work and not make it home alive. You could be walking your dog or having a family barbeque in the park—which a Black family happened to be doing on the day I went to look at the installation—and be threatened with the police being called on you. You may suffer a mental illness and have a terrible day, and instead of a crisis team of clinicians, the police show up. You may end up on the wrong end of a balcony, a taser, or a gun. We have graduated from risking death to survive to risking death just to live.

Progress.

“I think Black history is Canadian history, but I think there has been an erasure of the contributions of Black people to this country,” says Ogunlesi before extrapolating. “For instance, we have the Jamaican Maroons who were exiled to Nova Scotia and worked on a lot of the civic centres that still stand, which is Black labour that we all still get to enjoy but don’t know anything about. Thinking about the ties Canada has to all these different countries like Jamaica, I feel there’s a responsibility for our educational system to give kids a bare minimum of cultural education that they can build on later if they so choose.”

To illustrate the point, Ogunlesi points to the importance of his own education in making the Black Ark.

“I didn’t know this history until I was told in North Preston, which piqued my interest and pushed me to learn more,” Ogunlesi shares. “So it’s important to uncover these histories for all Canadians to understand better who we are—especially if we’re saying multiculturalism is something we are so proud of—it’s all our responsibility to know a little bit about the different cultures that make up our country because if not for this knowledge, this installation wouldn’t even exist.”

For Rufei, having this knowledge of self and understanding of your history allows one to see the future differently.

“I think what the work does well is it allows you to come in with an open mind and have your own experience, but I don’t think you can have that experience and leave the same person you came. I think the power of the project is to understand there is power in knowing our history and that we should acknowledge our past so we can confidently move forward. Also, our history can be the inspiration for beautiful art, and so many more stories need to be told in a way that isn’t too in your face but is still powerful.”

Both Ogunlesi and Rufai have Nigerian backgrounds, so I asked whether some of that cultural influence showed up in Black Ark.

“Thomas Peters, the man who lobbied to get the ships that would take Black Nova Scotians on that journey to Freetown, was born in Nigeria,” beams Ogunlesi. “So again, I had to make work about this since there was an even more personal connection to us, being that both our backgrounds are Nigerian, and other Nigerians coming here should know that we have history here way before our more recent arrivals.”

Of course, some might say no one who can trace their roots back to Africa, mainly because their family was never broken up by slavery, should make work addressing it. American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) and other Black people of that ilk have been accused of pitting Black immigrants against Black “Americans” by making these exact arguments. This includes anyone from the Caribbean, Africa, or anywhere else outside of the Americas. Never mind the shortsighted views revolving around who is deserving of reparations based on geographical location or even who gets classified as “Black.” In all the police murder videos I’ve seen, I’ve never heard a cop ask a Black person if they immigrated from elsewhere before killing them. Still, the elephant in the room may exist for some, so why not address it?

“As a Nigerian student at Howard University,” offers Rufai, “I not only learned a lot about African-American history, I was immersed in the cultural experience to a point where it’s part of who I am. My experience may not be your own experience, but there's a collective feeling.”

Ogunlesi points to what he sees as an overlap of cultures, making it almost necessary for him to address these histories in his work.

“I think once we all arrive here, as different as we are culturally, there is a grouping of Blackness that makes our experiences the same,” says Ogunlesi. “Personally, as a Black person, I share in the struggles of people who might be direct descendants of enslaved people, and I think I have a responsibility to make work about this. When you think about the journey of African people across the Atlantic, it’s been so mixed over time that I don’t think you can say anyone's Black culture is entirely distinct from the other, so I can learn about the history of my people throughout the diaspora and make work reflecting that.

In a recent Instagram post, Ogunlesi wrote…

“My dream is to have this work placed in the National Gallery of Canada as it “excavates the truths” about our country’s complicated history.”

When I ask him about it, he pauses thoughtfully, in the way someone so used to displaying their beliefs through actions that they don’t always think about needing to articulate them.

“I want the gatekeepers of our cultural institutions, grant funders and sponsors to see the impact art can have on the collective psyche of the entire population,” Ogunlesi replies. “With this work, so many people have said, ‘I didn’t know this or that,’ and now they know it. It makes people a little more sensitive to the struggles of Black people here and the relevance of our history now, by allowing people to better understand some of the systemic issues that are still in place.”

Black Ark can be interpreted as a reminder of enslavement or a journey to freedom. A damning of Canada as a country or a reminder of what we have been and how far we have still to go. Ultimately though, Black Ark is the truth.

Complex. Direct.

Exquisite. Vile.

Hopeless. Hopeful.

Dark. Reflective.

It’s an invitation to know ourselves in all our fragmented realities through a history that is finally beyond the ability to bury.

Sitting in plain view in a park in Ashbridges Bay from June 9 until September 5.

By

By