My visit to the Art Gallery of Hamilton on the afternoon of an unseasonably warm March day to see Michele Pearson Clarke’s new exhibit, Muscle Memory, was a pilgrimage of sorts. Returning to the city of my late-adolescent undergraduate days brought a refreshing wave of memories from my youth, the days when I had left home for the first time and felt liberated enough to explore and actualize my identity. However, with my disability also impacting my gender expression, I was not permitted to engage in the activities that would allow me to socialize with traditional boyhood and masculinity, like football, a sport in the blood of Caribbean masculine culture.

Doctor’s orders. Protecting my low vision above my emerging yet repressed rough-and-tumble masculinity was imperative. Stepping into the Muscle Memory exhibit was like a return to that unrealized boyhood that was within my Black body assigned female at birth. Those of us who navigate life expressing female masculinity can experience Pearson-Clarke’s installation as a place to honour that lost boyhood through a playfully immersive somatic experience that engages all senses, through soccer balls, awkward love songs and cheeky sparkle mustaches.

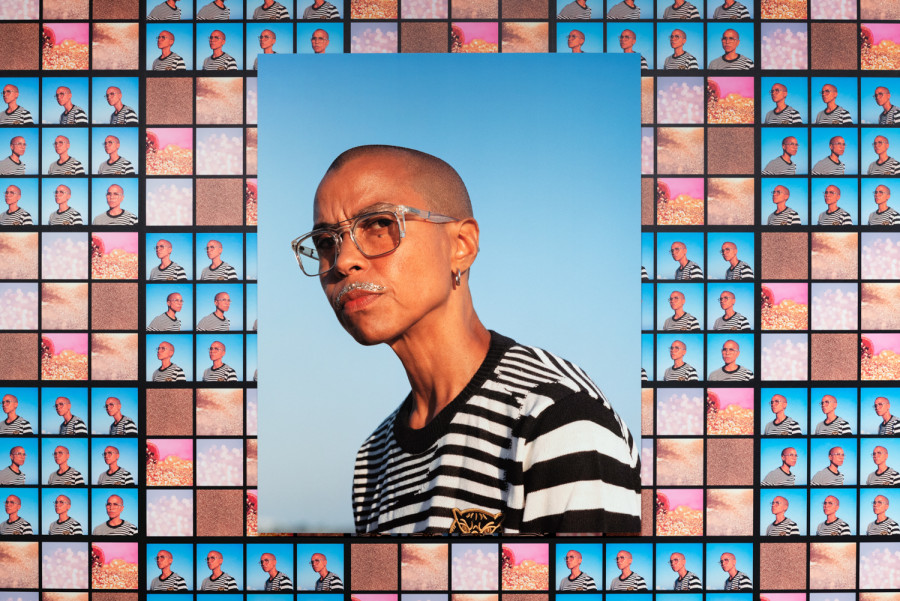

In her largest public art installation to date, Trinidadian-Canadian artist Michele Pearson Clarke speaks to the experience of Black Queer female masculinity by exposing the vulnerabilities and complexities of navigating the world within the body of a female who is Black and masculine-of-centre. Pearson’s collection of work shares the playfulness, joy, loss, grieving and experimentation involved in the process of coming of age within a Black female, masculine body. Titled Muscle Memory, Pearson Clarke’s exhibit brings together video, self-portraiture and intentional object placement to create accessible, cross-media dialogue and engagement with the work.

Upon entering the main gallery, the viewer encounters a makeshift football pitch covering the gallery floor. The space is set perfectly with near-mathematical precision, divided into a grid of neon pylons and footballs. It generated a childlike joy that transformed into a sense of adult mourning, as memories of growing up as an unrealized and unaffirmed masculine female child came to mind. I wanted to play. I wanted to kick each of the balls from their neatly assigned positions. I wanted to gleefully break the socially constructed grid of gender identity and witness the child who had to suffer coercive and compulsory femininity, the category assigned at birth and enforced throughout my childhood. As the urge to play ensued, I grieved for the child who never got to play and watched those assigned true “boys” from the sidelines. The fact that I could not play outside the lines of the strict Caribbean and Christian gender roles was a travesty.

Situated at the center of the gallery football pitch is a custom-built architectural structure that surrounds the viewer with video and sound from four directions. Each screen depicts a masculine-presenting participant, including Pearson-Clarke, moving through the process of overcoming insecurity, worry and shame of being a bad singer. Together each participant performs vocal warm-up exercises, leading to a boisterous choral finale of the performance of a pop song.

Through the communal practice of voice, each participant witnesses the other, holding space for their unique sound. They experiment, mix various combinations of their voices, and then acquire a shared experience to conclude the video presentation with confidence and camaraderie. The combination of the custom architecture of the space and the proprietary blend of each singer’s voice is symbolic of how Queer identity and Queer relationships are custom jobs. These singers were my friends and I, young, verdant and emerging in the fullness of our realized gender, finding our voices together, holding space for the cracks and dips in our tone of voice, finding our way through to the melody of our beautifully Queer, female and masculine lives.

At the age of 35, better late than never, I am learning to pursue my transmasculine being on a deeper level. Pearson-Clarke’s Muscle Memory invokes a process of retrieval of rituals that were overlooked, unrealized rites of passage, and missed memorable moments of graduating to the next step in our growth in the direction of completing the expression of our inborn spirit. It could be rituals of shaving, competitive team sports, and the markings of a typical boyhood and young manhood that every queer, trans nonbinary adult of colour may experience in their teens.

My expressions were always chosen for me by social circumstances and social constructions of gender expression. Before I could express my wants, there was no opportunity given to answer the question of what I wanted and how I wished to present my body. I learned that it was good to pursue what felt good in my older years. Pursuit of the path of defining and clarifying my voice, the pursuit of self-actualization as a transmasculine black person. Pearson-Clarke’s exhibit Muscle Memory affirms Black female masculinity with playful joy.

Muscle Memory is exhibiting at the Art Gallery of Hamilton until September 5th, 2022. Tickets are required to view the exhibition in Gallery Level 1. Adults are $15, Seniors are $12, and Students are free.

By

By