Provincial and regional government-funded organizations such as the African and Caribbean Council on HIV/AIDS in Ontario (ACCHO), The Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention in Toronto, and Moyo Health and Community Services in the Region of Peel are on the frontlines of combating the spread of HIV within the Black community by raising awareness and providing critical education and services to people seeking discreet testing and treatment. Over the past 2 years, these organizations have boosted their efforts to support the rising numbers of Black women testing positive for HIV. ByBlacks sat down with Ky’oksinga Kirunga, Executive Director of ACCHO and Racquel Bremmer, Board Chair of Moyo Health & Community Services to have both experts shed some light on the urgent needs facing Black women in the HIV pandemic.

Kirunga has worked in the HIV/AIDS sector for over 14 years within Canada and Internationally and has helped lead positive conversations on HIV and AIDS within the Black community by meeting Black women where they are. She encourages Black women to seek regular HIV testing as a form of “radical self-care.” In 2020, ACCHO Launched the Care Collective, a campaign for and by Black women that encourages routine HIV testing. Last year, The Care Collective launched a series of events called The Care Salon, a pop-up clinic initiative at local Black-owned hair salons, offering on-the-spot HIV testing. The Care Salon also helped to address the barriers around accessibility, education and the stigma surrounding getting tested for HIV. “The salon partners who participated in the Care Salon were certainly taking a risk,” Kirunga admitted. “Stigma begets stigma and Black people are tired of being associated with things that further marginalize them or shed a negative light on the Black community. Black women especially already live in harm’s way due to socio-economic reasons: systemic limitations in finances, precarious refugee status, working long frontline hours and other factors add more layers to the injustices Black women face. It’s not talked about in the family, in churches and other places where Black people gather. Black folks are already hyper-sexualized and don’t want to be connected to things that further stigmatize them.”

This stigma associated with sexuality and HIV has only caused Black women to absorb the impact of the HIV pandemic in Ontario. The silence around HIV and AIDS is affecting the health of the Black community. In both life and mainstream media, Black women tend to be made invisible, including Black trans women.

Black women are taking on the burden of care within the nuclear family, within spiritual centers, at work and within the community. Kirunga added, “Thinking about yourself and your health is what comes last for Black women. We don’t take the time to think about our health and our inherent self-worth. We are not appearing for doctor’s appointments, seeking regular testing or taking the time to understand our own health. We are last within our own minds because we are taking care of everyone else. We also experience difficulty negotiating safer sex with our partners and life partners. Black women’s neglect of self-care is what inspired the creation of The Care Collective. Putting health care as self-care at the top of the priority list is one of the goals of The Care Collective. If Black women spoke about and sought regular HIV testing, just as often as they would a mammogram, early detection can make all the difference in getting treatment and maintaining a healthy life.

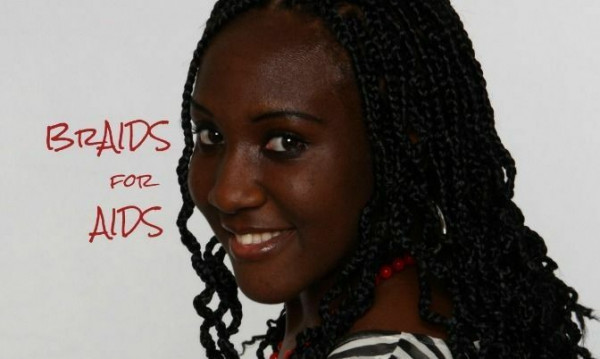

Braids for AIDS is one event that ACCHO has supported to encourage conversation in warm and welcoming environments where Black women already feel comfortable. Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, The Care Collective has launched online programming to support the self-care of Black women by offering online events, yoga classes and open conversations about HIV and HIV prevention. ACCHO and many other AIDS Service Organizations have had to rely on social media for the promotion of educational resources and services. There are still many within the Black community who need to be reached with HIV/AIDS education and resources - including the trans, non-binary and gender-non-conforming Black community. “No one is talking to them,” Kirunga noted. “We have been asked to create programs specifically for their unique needs.” While trans-identified individuals continue to be marginalized within the Black community, silence about trans people and trans health must also be broken for the sake of our collective wellness as a Black community.

AIDS Service Organizations that target the Afro-Caribbean and Black population are hard at work across the Greater Toronto Area, encouraging Black women to have open and honest conversations about HIV and regular testing. Racquel Bremmer is the Board Chair of Moyo Health and Community Services, a rapidly growing AIDS Service Organization Serving the Region of Peel. Bremmer is a 27-year HIV/AIDS healthcare veteran who has worked in HIV/AIDS education and healthcare in Jamaica and Canada. She has seen the devastating impact of the virus on the Black community in the Caribbean and in Canada. She has also seen the numerous medical advances that have been made in HIV/AIDS healthcare since the onset of the pandemic, making HIV reach the status of a chronic health condition that rarely progresses to AIDS if adequate treatment is received.

When Bremmer began working in this sector, antiretroviral therapy, like AZT had devastating side effects and their availability in the Caribbean was limited and costly for the average citizen. She saw many people die due to the lack of access to affordable medication or due to stigma and discrimination. Many healthcare workers were not comfortable or educated and would restrict healthcare at times to those living with the virus, due to fear and ignorance.

Treatment has been so successful in the past decade that in many parts of the world, HIV has become a chronic condition in which progression to AIDS is increasingly rare. Throughout her career, Bremmer has watched the emergence of U = U campaigns (Undetectable = Untransmittable) which have helped to normalize the conversation around sex and sexuality for people living with HIV in mixed-status relationships, (where one partner is HIV+ and the other is HIV-).

Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy improves overall health and now prevents sexual transmission of HIV. The goal of treatment is to achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load. Studies have shown that effective antiretroviral therapy prevents sexual transmission of HIV. Bremmer notes that she has also seen the integration of government-funded HIV healthcare services in the community with the creation of AIDS service organizations and HIV-specific programming that center prevention, health promotion and education in the heart of communities that experience systemic marginalization.

Throughout her career, Bremmer has also identified the increasingly high rates of Black women affected by HIV for many reasons that are closely linked to the disadvantages faced in all social factors of health, when compared to women of other races. There is a close link between intimate partner violence and HIV and intimate partner violence can increase the risk of HIV by limiting a person’s ability to negotiate safer sex and safer drug use. Intimate partner violence is common among people living with HIV, in part because intimate partner violence and HIV disproportionately affect Black women, which can be observed in women’s shelter occupancy rates across Ontario. Black Women and trans folks living with HIV experience more severe or more prolonged intimate partner violence than people who are HIV-negative and experiencing intimate partner violence, and are particularly more vulnerable to intimate partner violence when they disclose their HIV status to their partner.

Both Kirunga and Bremmer would agree that in order to combat the HIV pandemic within the Black community and especially among Black women, a multi-faceted educational approach must be engaged. Health promotion programs that meet Black women where they are, in culturally-relevant ways, across multiple languages and within diverse faith communities is imperative to ensure that consciousness is raised about how Black women can protect themselves from HIV infection. A social justice approach that addresses the social factors of health (such as racial, social, gender and economic injustices) must be engaged by community and government agencies in order to close the gaps of inequities that put Black women and Black trans people in harm’s way. Putting accessible tools and resources in the hands of Black women and trans people (such as self-testing and prevention kits) year-round and not just during Pride month are key to fighting the spread of HIV.

By

By