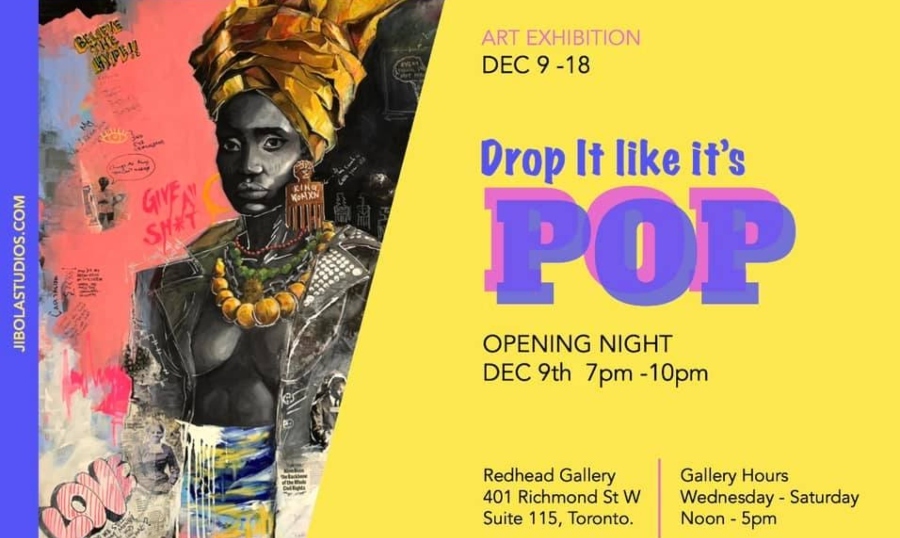

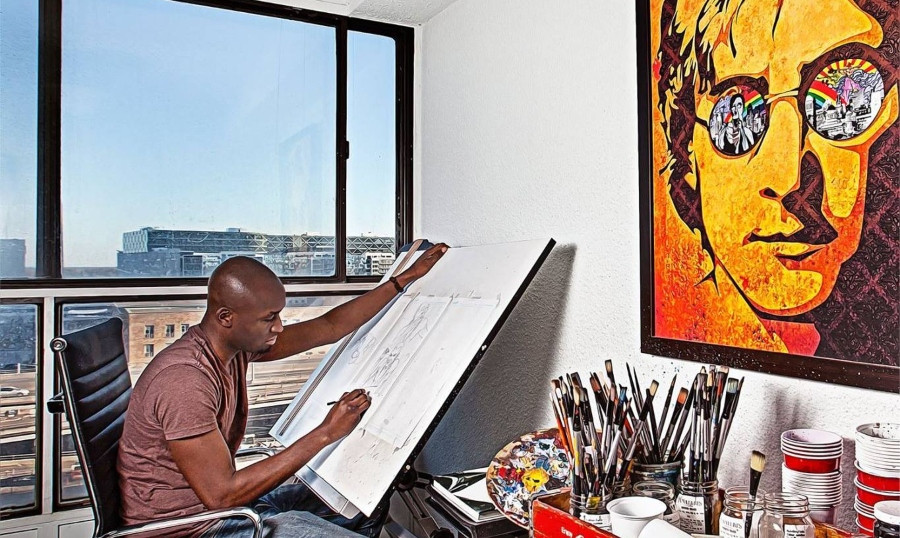

A lot has changed for Nigerian-Canadian artist Jibola Fagbamiye since we last spoke in 2019. For one, he’s now a father. He’s also a soon-to-be-published graphic novel illustrator and co-writer with HarperCollins Canada. Finally, this month, he exhibits the evolution of his artwork at Toronto-based Red Head Gallery for a show entitled, Drop it Like It's Pop. The title alludes to his Pop art style and the urgency of the time in which we live. All of these arteries intersect and somehow pump life into his creativity, led by a brain that informs the artist’s heartbeat.

Fela Kuti Graphic Novel

“The first time the graphic novel came to me was after I’d seen the play on Broadway in 2010,” Fagbamiye said, reflecting on FELA! The Musical. “I grew up in Nigeria and I’d walk past Fela Kuti’s house to get to my aunt’s house in Ikeja, Lagos.”

Fela Kuti, the Pan-African multi-instrumentalist and frontman, was more than the father of Afrobeat, which merged Yoruba percussion and vocals with American funk and jazz. He was a socio-political powerhouse who embodied the phrase “speak truth to power” in a way that few entertainers have and is the inspiration for Fagbamiye in both life and art. Fela was not a “Twitter warrior” who assumed the role of activist or radical for “like” or “follows” or one who adapted their opinions to the preapproved stance of “whatever” famous political leaning for the significance of virtue signalling. Fela took some severe risks speaking out against a military regime. In short, shit got real.

“I’ve been obsessing and writing about it for a while,” said Fagbamiye, whose graphic novel focuses on an important moment in Fela’s life; when his house was attacked by soldiers who beat him to a pulp and threw his mother out a window. “Nobody went to jail, and nothing really happened. We just moved on. So the story centers around that.”

Fela’s mother (Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti) was an important figure in Nigerian history who helped negotiate Nigeria’s independence from British rule and launched the Abeokuta Women’s Union, as well as being associated with some of the most important anti-colonial educational movements in Nigeria and West Africa. According to Fagbamiye, in Nigeria, you can figure out someone’s economic class by how they talk about Fela. Whether working class or an upper-class member, his influence still resonates today.

Fagbamiye left that play in 2010 with an idea for a graphic novel that told Fela’s story outside the confines of the “trauma porn” often inserted into Black diaspora stories in popular culture today. That’s not to downplay the traumatic events of our history and experiences but rather to provide context to the trauma.

“I wanted to talk about art, music and love in a layered, nuanced way around the trauma because I notice that even most Nigerians don’t know much about Fela,” Fagbamiye states. “There’s just these pieces of history I wanted to talk about that told the story more richly, so that if there were a Fela movie or series, this novel would be a good reference point that celebrates Fela’s life in a way that’s also fun and entertaining.”

Fela Kuti Graphic Novel Courtesy of Jibola Fagbamiye

Fagbamiye, a producer of brilliant visuals in any of his chosen mediums, brought on a co-writer in 2015. His friend, Conor McCreery, who is white and very Irish Canadian, had lived in Kenya for a few months but was initially hesitant about working with Jibola on the project.

“Conor co-wrote this phenomenal comic book series called, ‘Kill Shakespeare,’ where all of Shakespeare’s characters are trying to kill Shakespeare,” says Fagbamiye. “I asked him if he’d do it with me, and he was hesitant because he’s White. It’s complicated within the cultural context of how we live now, but he knows a lot about Fela and is knee-deep in that history.”

The pair began working on the book and pitched it to HarperCollins in 2020. “They loved it, told us to work on it, and then Covid hit,” recalls Fagbamiye.

Then, radio silence.

“So I’ve been working on this since 2010, Connor came onboard as a co-creator in 2015, we eventually get a book deal in 2020, then COVID happens, and it all disappears. They didn’t say no. There was just nothing said,” Fagbamiye says, at the time thinking COVID had killed his project.

“We just kept working on it and, this year, the publisher reached out and gave us the green light to go ahead,” Fagbamiye beams. “They gave us a contract, so I was able to announce it to the world, and here we are.”

“Drop It Like It’s Pop” Art Exhibition. Why Now?

“I’ve looked over my work the last ten years and realized that it has evolved,” Fagbamiye explains. “It’s still classic pop art, but the world has changed, and my work has become grittier in a way, I think, subconsciously reflects that. My politics has become more concrete and gritty; I’m a leftist who has become more aware of being a leftist and has the language to express how I feel in my work.”

Courting controversy can be a tool of opportunistic entities with less than selfless interests. It’s often executed awkwardly and can be recognized as a marketing ploy or political spin by anyone caring enough to Google search the entity’s track record. (re: Pepsi’s Black Lives Matter Kardashian ad, or the Canadian government’s participation at COP26 in the same week the RCMP were cracking the heads of Wet'suwet'en oil pipeline protestors and arresting journalists documenting it). The most controversial observations are usually the most obvious in a world that still glosses over these sorts of manufactured optics.

“I don’t think my thoughts are controversial, or at least I don’t believe they should be,” Fagbamiye insists. “In the early 2000s, we had this utopian vision of what the world would be with the internet (re: “information superhighway”), and it’s sort of instead become this weird world of corporate feudalism where we’re the serfs, and there’s a group of elites with much more power. Take the pandemic, for instance. It’s so evident that if you have a vaccine for the pandemic, it should be given freely to the rest of the world so we can all just go about our business, but we can’t because a group of elites have decided they need to profit.

"By Any Means Necessary" and "Billie" Courtesy of Jibola Fagbamiye

“Initially, my pieces were all smooth and on delicate glass, but now they’re on textured wood with elements of oil and paper where I’m etching what I feel into the work as I’m creating,” says Fagbamiye. “It’s just a little rawer than before, and I think it should be out there because it doesn’t do anybody any good if it just sits in my brain.”

The Pop Art elements referencing his earlier work are still very present and make the addition of political messaging somewhat subversive. By its very nature, placed in a society that treats celebrity culture as a religion and values celebrity status as “godhood,” the new work can’t be anything less than provocative. Which, according to Fagbamiye, harkens back to the origins of the 1950s Pop Art movement and artists like Warhol.

“I don’t know if it changes anything, but maybe fifty years from now, assuming we’re not all underwater, someone can reference it and know what was happening,” Fagbamiye says.

“When you think about when Pop Art came out in the 1950s, it was at a time of economic expansion. The White middle class was moving out to the suburbs and told to buy a new car and a house while, at the same time, there were these mass protests for civil rights, gay rights, women’s rights, etcetera. The establishment was saying ignore those weirdos, and pop art came out of that sense of optimism about the future amid struggles for change.”

Far from living The Jetson’s lifestyle people of that age envisioned for us, we seem to be right back in the same place as a civilization. All the homes in Toronto are worth millions of dollars, but few who own them actually live in them. Meanwhile, homelessness is at a crisis point, and when a private citizen takes it upon himself to build makeshift shelters, the City of Toronto threatens to sue him. It might be easy to be pessimistic about the world to anyone with a soul left paying attention. Still, Fagbamiye isn’t interested in apathy or apolitical stances leading to nihilism.

“Even though we don’t have a lot of power, don’t know what kind of future we have or if we even have a future, we still have to create, and love, and just be,” says Fagbamiye. “That’s what’s coming out of my art.”

Fagbamiye is working in the tradition of his countryman Fela Kuti, another artist who spoke truth to power in a way that managed to spark joy in all who encountered it.

“Whether through graphic novels or gallery art, I’ve always wanted to tell stories,” offers Fagbamiye. “I want the viewing public to connect with my work and hope it tells them something about themselves. Maybe I’ve become more transparent in how I present my work because I’ve been so immersed in Fela and Pan Africanism that it has started to seep into how I present the story, my work, and my politics.”

As per Fagbamiye, what’s truly beautiful about pop art is it is as much about celebration as a protest. Jibola Fagbamiye’s work is embedded firmly in those roots.

“It’s a privilege to be able to go out and experience art that makes you think about serious things in a beautiful white-walled building,” says Fagbamiye, happy to give people a safe reason to leave the house after being cooped up for two years.

“I want people to leave stimulated and hopeful, but also with an understanding that we are the ones we are looking for to save us from ourselves,” reiterates Fagbamiye, wanting his work to be visually appealing while having an impact.

“I just want that top of mind even as you enjoy a piece of art.”

Jibola Fagbamiye's latest exhibition of new work, "Drop It Like It's Hot", debuts with an opening launch on December 9, and the Fela Kuti graphic novel is slated for a Fall 2022 release.

By

By