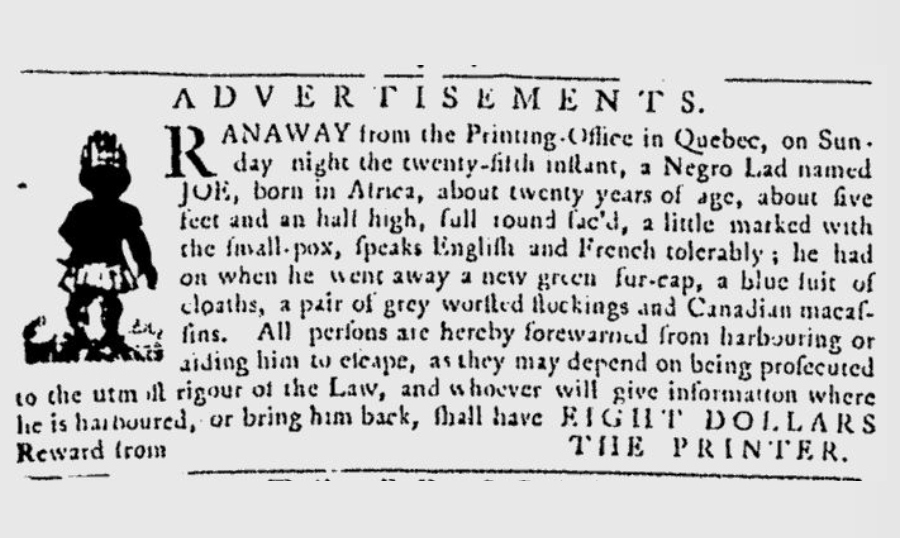

You only need to look at the documentation of slavery in New France (Quebec) and advertisements (compiled by NSCAD University Professor of Art History Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson) taken out in newspapers for runaway slaves to understand some of this complicated history. Even after Britain abolished slavery throughout the Commonwealth, Black Canadian scholar and author Robyn Maynard’s seminal *book, “Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present” points out how “sundown laws” were informally enforced to criminalize Black folks for being out in public after dark. Moving ahead to the 21st Century, the practice of “carding” allowed police officers to stop, question, and document individuals without any evidence to suggest they had committed or had knowledge of a crime. According to a 2018 Human Rights Commission **report investigating racial profiling and discrimination by the Toronto Police Service, Between 2013 and 2017, a Black person was nearly 20 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a fatal shooting by the Toronto Police. Therefore, Black people taking up public space in any safe, esteemed or meaningful way should inspire pride if for no other reason than it’s possible to do so.

Quebec Gazette, January 29, 1778 (Courtesy of Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson)

To that point, Toronto-based photographer Jorian Charlton’s “Untitled” was installed above the streets of Toronto’s Financial District last week as part of the city’s “2021 Year of Public Art” initiative ArtworxTO and Project Reframed, an initiative providing visibility for emerging artists of colour that challenge notions of belonging in traditional art spaces. I stumbled upon Charlton’s installation after turning a corner onto the bustling street, reanimated after a year of lockdowns. The majestic 70-foot tall photo displays Blackness in a way that’s both regal and beyond the accepted confines of gender, in an area of the city where the presence of Black gender non-conforming folks isn’t necessarily highlighted nor expected. It stopped me in my tracks and for a moment, I had to collect myself before rifling through my jacket for my phone so I could take the obligatory photo. It struck me as somewhat poetic that, in a city where the work of Black artists hasn’t traditionally been acquired nor shown by galleries with any regular frequency, their influence has suddenly grown beyond anything the galleries could contain. Creativity held captive by COVID-19 lockdowns and systemic anti-Black racism has finally been given release in the form of artist introspection, intervention, and societal reflection all over Toronto.

Nina Chanel Abney's "Generally Speaking" in Yorkville (Courtesy of ArtworxTO)

Also affiliated with ArtworxTO is New York-based artist Nina Chanel Abney’s “Generally Speaking” located at 29 Bellair St. in Yorkville. For those of you unfamiliar with Toronto, Yorkville is an enclave for the wealthy who prefer the urbanity of downtown life to the simulated suburbia of other tiny neighbourhoods in the city. In the 1960s, Yorkville was closer to New York’s bohemian Greenwich Village than the Upper Westside profile it mimics today. Counterculture protests to ban cars from the neighbourhood led to clashes between the police and residents, and developers were given the green light by the city to buy up decrepit buildings at rock bottom prices. By the 1980s, Yorkville’s colonization by high-end retailers and real estate magnates was complete. Of course, the nature of this new world catered to a relatively homogenous, if not moneyed, clientele. In the face of that history, Abney’s “Generally Speaking” both reclaim Yorkville’s counterculture history of art and activism while claiming space to resist anti-Black racism and gender-based hate. With the words, “Stop”, “Don’t Kill”, and “Love” scrawled throughout the mural, the statement by curator, Ashley McKenzie-Barnes, asks pedestrians to “stop for a moment of consideration on how we can embark on a communal process of healing through art and intentional contemplation.”

Esmaa Mohamoud’s “The Brotherhood FUBU (For Us By Us)” at the Westin Harbour Castle Conference Centre (Courtesy of the Artist, Georgia Scherman Projects and CONTACT, Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid)

Down by the waterfront, Esmaa Mohamoud’s “The Brotherhood FUBU (For Us By Us)” overlooks bypassers on the street below. In her Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival statement, the Black Canadian artist says, “FUBU pushes against racialized depictions of Black men—which often focus on the subjects engaged in acts of labour or conflict—by positioning them as boldly united figures asserting their presence in the physical and cultural landscape.“ As with Charlton’s work, stereotypical representations of Black masculinity are challenged by the 37 x 144-foot banner whose pair of models (Noah Brown and Timothy Yanick Hunter) stare back at the viewer. The idea of the White gaze is turned on its head as you raise your eyes to the colossal image of Black men in durags. As they peer over their shoulders, I reflect on my own hypervigilance as a Black male navigating urban spaces. In this context, however, their piercing glare seems to ask the question, “whose gaze holds power now?” Staged before a body of water, their presence could as easily be a reference to the harbour nearby, as to the forced journey of the enslaved ancestors who came before them. The models, one light and the other dark-skinned are connected by a single strand of a black silken garment; the brotherhood that binds them perhaps related to the historical weight of the water before them.

Thomas J. Price "Within the Folds (Dialogue 1) on the corner of Dundas & McCaul (Courtesy of The AGO)

Thomas J. Price is a London UK artist who uses sculpture, film and photography to engage with issues of power, representation, interpretation and perception in society and art. At a time when society is questioning who we build monuments to and if what they represent is still worth monumentalizing, Price’s sculptures challenge traditional cultural narratives. The AGO (Art Gallery of Ontario) plays host to “Within the Folds (Dialogue 1)”, a nine-foot-tall bronze cast figure depicting a Black male subject standing casually while gazing off into the distance in a hooded sweatshirt and pants. The sculpture towers over passersby and is located on the exterior grounds of the gallery, steps from the art university OCADU. Bronze, a material that has historically denoted power and prestige, subverts colonial standards of who has value when used to represent the traditionally overlooked everyday Black person. Here, there isn’t a necessity to mimic the accoutrements of the Western world standard. The average Black person is worthy of taking up space just as they are.

Queen Kukoyi, Nico Taylor and Quentin VerCetty, "Olamina" formerly located at Aitken Place Park (Courtesy of the Author)

In terms of sculpture, Black women were also represented by “Earthseeds: Space of the Living”, a project developed by BSAM Canada for the first Toronto Waterfront Artist Residency that unfortunately had its last week down by the water on November 5th. “Olamina” was an installation inspired and named by the main character in author Octavia Butler’s Parable series (Lauren Oya Olamina) as well as the African water deity Mami Wata. Collaboratively designed by Queen Kukoyi, Nico Taylor and Quentin VerCetty, the sculpture intersects Yoruba symbolism, Afro-Caribbean folklore, isolation and space for contemplation as a result of COVID-19, and our relationship to the earth, water and community at a time where all those things are extremely relevant to our lives. Without water, there is no life. As such, the placement of Olamina by Toronto’s waterfront calls us all to reflect on what a powerful source of spiritual and physical healing our natural world can be to us and the necessity of our role in protecting it. By protecting our environment, we protect each other. Hopefully, Olamina will find another outdoor location to be viewed by the public. When it does, if you haven’t seen her, I suggest you take the opportunity to do so.

To normalize the Black figure in places that have been presumed foreign to us is truly an indicator of how far we’ve progressed as a people and perhaps a culture. Even more fascinating is this is by no means an exhaustive list of Black artists taking up public space in Toronto. To be Black and alive at this time is to experience recognition of our presence in a way that was never a given. That being said, how society reacts to that presence, with appreciation or resistance, will be a reflection of society’s progress as a whole.

Source Material:

*Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present, Robyn Maynard, Fernwood Publishing, 2017.

**A Collective Impact: Interim Report on the inquiry into racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black persons by the Toronto Police Service, Ontario Human Rights Commission, Approved November 2018.

By

By