While Canada has its own issues, the news coming from the United States is worrying: new U.S. president Donald Trump issuing executive orders to end diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs in federal departments, the reduction of DEI initiatives at major employers like Target and Home Depot, and the banning of books like The Color Purple and The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

What’s happening in the States makes me ask: can Black history be erased?

The short answer? Yes.

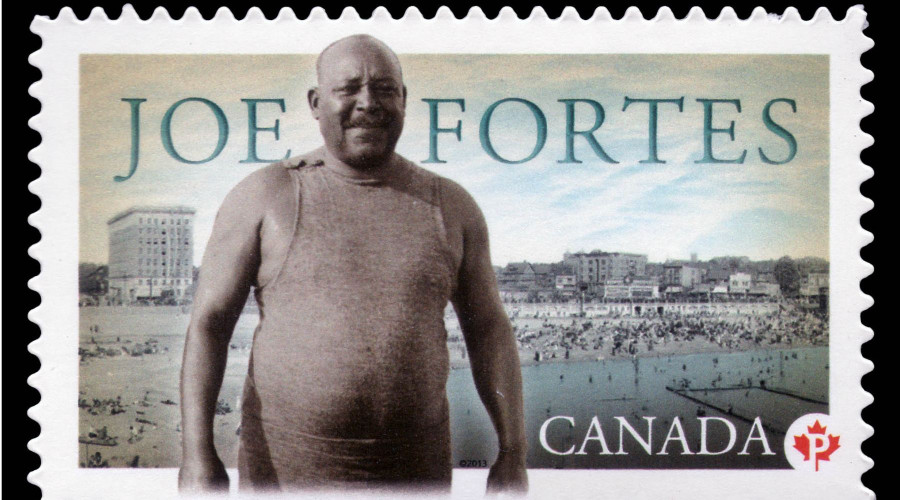

Learning our history as Black Canadians, keeps our stories—and our history—alive. There is power in passing down these stories and our history to our children. As we wind down Black History Month, there is still time to learn about Black Canadian historical figures, like Seraphim ‘Joe’ Fortes, who patrolled Vancouver’s English Bay beach over 100 years ago.

Joe Fortes is often recognized as Vancouver’s first lifeguard, who saved at least 29 people from drowning and taught three generations to swim.

“I teach them to swim, as I have done some of their fathers and mothers,” he told The Vancouver Sun back in 1920. “I look after their safety, and they call me their friend. I can safely say I have more kiddie friends than any man on the coast, and their friendship is worth having.”

In 2013, Canada Post issued a memorial stamp featuring his image, but I only heard about Joe Fortes when I spoke to Ruby Smith Diaz, an Afro-Latina artist and author, who explores his legacy in her book, Searching for Serafim: The Life and Legacy of Serafim 'Joe' Fortes.

“Without Black history, Canadian history is incomplete,” she said. “Black history is Canadian history. Indigenous history is Canadian history. Without the narratives of the racialized communities that have built this country, we don’t have a true sense of our past.”

Forgetting these stories isn’t just a loss of knowledge, but it’s dangerous because we lose historical context. “We lose track of how different events come together to create conditions that endanger our communities,” explains Smith Diaz. “We lose sight of strategies that have been used to marginalize us, and that makes it easier for history to repeat itself.”

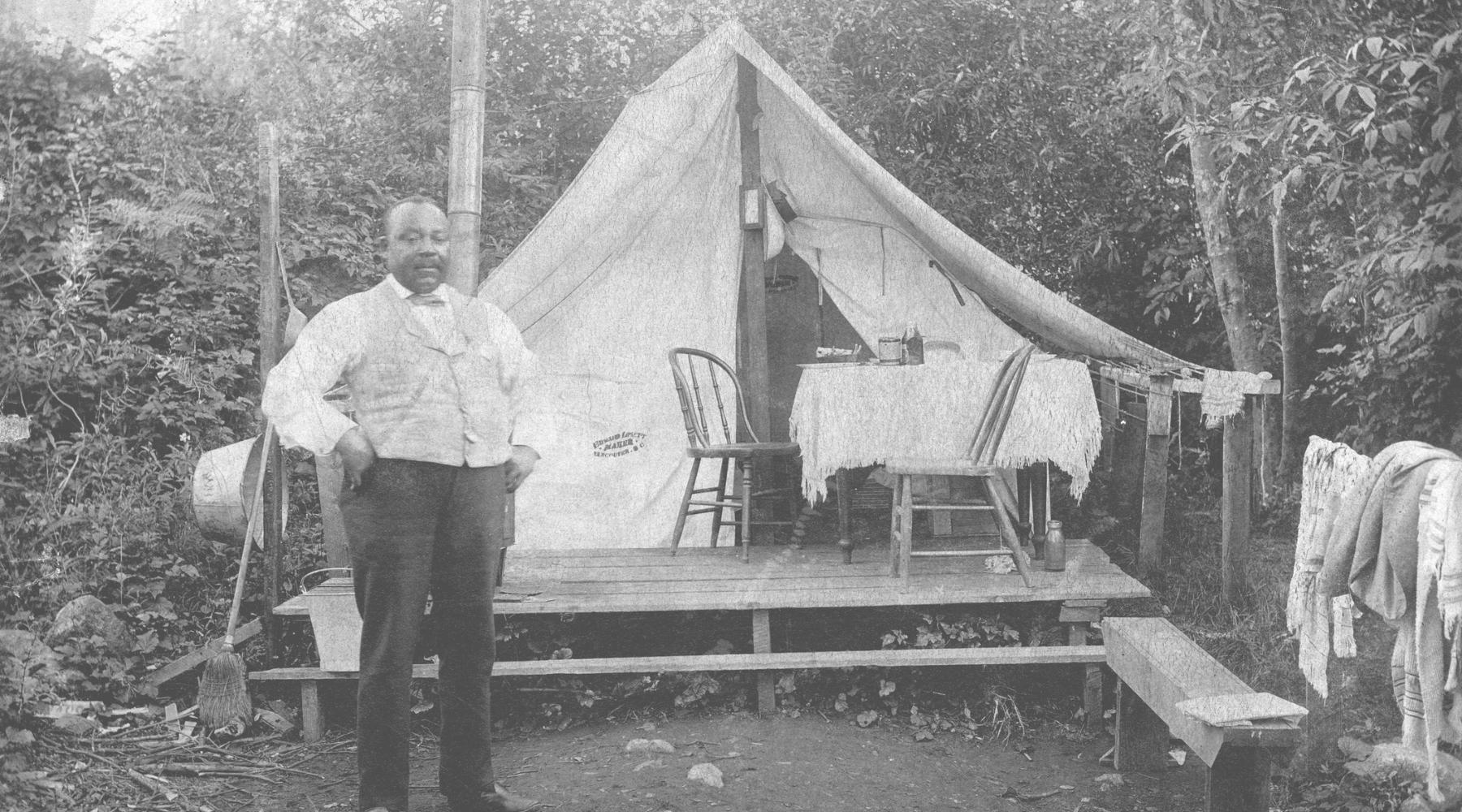

Joe Seraphim Fortes in front of his tent at English Bay. Source: Vancouver Archives.

Joe Seraphim Fortes in front of his tent at English Bay. Source: Vancouver Archives.

Black Canadians have often been a footnote in our country’s history. Stories like Fortes’ allows us to see ourselves in the story of Canada—and educates others of our deep roots. Smith Diaz’s learned about Fortes through an art challenge that encouraged participants to highlight Black historical figures. While searching through Vancouver’s archives, she saw a photo of Fortes.

“There’s this one photograph in particular where he’s standing in a vest, very done up, with his hand on his hip and a confident look on his face,” she recalled. “It was set right in the middle of what is now downtown Vancouver. That image really pulled me in.”

It wasn’t only the photo that captured her attention, it was Fortes’ Afro-Latino heritage—like her own. “I had never come across a story of a more prominent Afro-Latino person in Vancouver before,” she said.

Seraphim Joseph Fortes was most likely born in Port-of Spain, Trinidad (although some reports say Barbados) in February 1863. He moved to England in the 1880s and settled in Vancouver in 1885.

Joe Fortes diving into water at English Bay. Source: Vancouver Archives.

Joe Fortes diving into water at English Bay. Source: Vancouver Archives.

Fortes, known for his volunteer work and love of the beach, became the unofficial guardian of English Bay, his favourite swimming spot. In 1900, the City of Vancouver hired Fortes as a special constable with duties including lifeguarding, swimming instructions, and beach patrol. His legacy as a lifeguard and a rescuer in the Great Vancouver Fire of 1886 earned him widespread admiration. However, his rise to prominence occurred against the backdrop of overt white supremacy.

“What captivated my interest is how he was elevated by Vancouverites to this level of fandom,” Smith Diaz said. “But some argue that he became more of a mascot than a hero.”

While Fortes was celebrated for his service, Vancouver was actively engaging in racist policies and violent acts against Asian and Indigenous communities. Smith Diaz referenced the 1907 Vancouver anti-Asian riots, where city councillors marched under banners reading, "Stand for a White Canada."

Joe Fortes teaching a woman how to swim. Source: Vancouver Archives.

Joe Fortes teaching a woman how to swim. Source: Vancouver Archives.

“I always wonder, how were those two things able to exist at the same time?” she asked. “Why was he so loved or respected, yet at the same time, people at the beach where he worked were also taking part in these acts of violence against other racialized communities?”

While Joe Fortes was celebrated, he is a problematic person. He was known to surveil Chinese communities and abuse his role as a constable. Embracing our history means humanizing our historical figures because they aren’t perfect. “If we want to build a just society, we have to engage with our history honestly. That means looking at our heroes with complexity, learning from their flaws, and using those lessons to move forward.”

While doing research in 2022, Smith Diaz found a postcard featuring an image of Fortes with a handwritten caption: “This n*gger has saved many lives. With love, R.”

“I found it on the Vancouver Heritage Foundation’s website,” Smith Diaz recalled. “It was just posted there, right in the centre. I thought, ‘Did nobody read the handwriting on this?’” After raising concerns, both the foundation and the Vancouver Archives removed the image from public view. The message and the fact that no one thought it was harmful summarizes Vancouver’s—and Canada’s—“love-hate relationship with Black communities. It’s a stark reminder of how racism can exist even in spaces where we are supposedly celebrated.”

Fortes’ story can be seen as an interesting Black Canadian story, but it’s more than that. We can use Joe’s story to add context to the Black experience in Canada and who we are as Black Canadians. Smith Diaz is inspired by the Chilean concept of memoria viva, or ‘living memory.’ “It’s about keeping our history alive. My mother left Chile because of the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. People went missing because of who they were or their resistance to the dictatorship. If we don’t keep watch, if we don’t take action, history will repeat itself. And that’s something we must actively fight against.”

Joe Fortes’ story is just one of many overlooked contributions by Black Canadians who have helped shape this country. For every recorded name, how many others remain hidden? When we uncover these stories, we gain a fuller, richer understanding of Canada’s history—not just for ourselves, but for our children. History isn’t confined to books; it lives on when we share it, ensuring these stories and people are never forgotten.

By

By