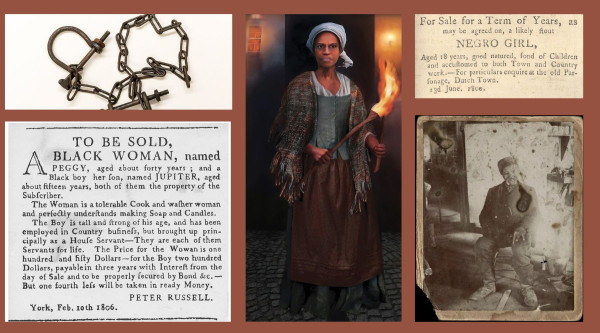

Black people had to attend segregated schools, use separate bathrooms, and were prohibited from living in the city unless they were menial labourers or servants. Those were among some of the only jobs Black people could get at the time, but the Bohee brothers had a different fate.

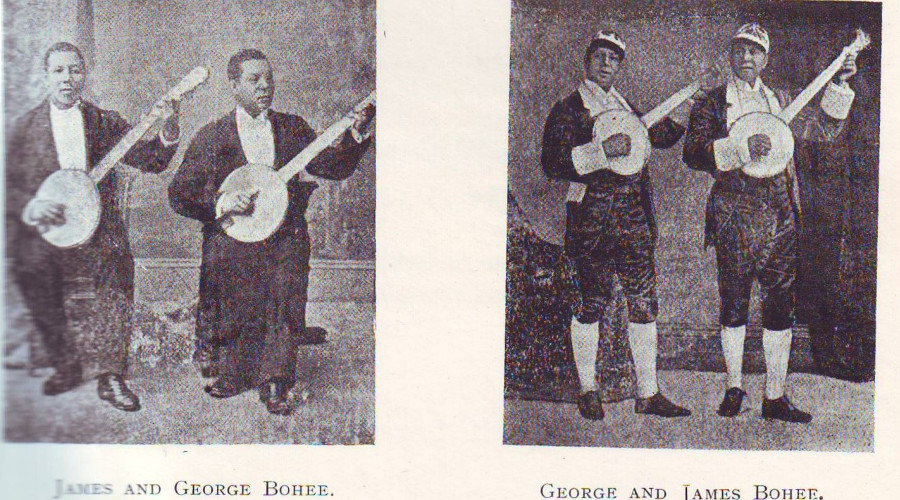

They would go on to become some of the most famous musicians in the world, popularizing the banjo across North America and the UK. But in Canada, hardly anyone knows their name.

The banjo's history has been whitewashed as originating in white Appalachian culture, but the instrument is a product of the slave culture of the Antebellum South. It likely had its origins in an African instrument known as the “mbanda.” It is thought that the first instrument of this kind used a hollowed-out gourd with a wooden neck employing four strings.

While information on the Bohee Brothers is not widely accessible, Peter Little, genealogist and historian for the New Brunswick Black Historical Society, has shared information from a still work-in-progress piece he is writing about famous Black New Brunswickers called The First and The Famous. He has shared that sometime before 1867, the Bohee family moved from Saint John to Boston, where James and George first heard the twang of a banjo.

By 1867, when the Bohee Brothers were suspected to be in the USA, Congress had finally given Black people the right to vote. But the threat of racial violence and death by lynching was very much real.

After mastering the instrument, despite what may be perceived now as a controversial choice, the Bohee Brothers formed the Bohee Minstrels in 1876. Minstrel shows were an American form of theatre in which white people would wear Blackface to comically portray the racial stereotypes of Black people. These stereotypes depicted Black people as lazy, dimwitted, superstitious and even happy-go-lucky during a time of racism. Often, minstrel songs also laughed at the violence and horrors that befell Black people.

Little tells us that the minstrel show led the Brothers from the US to the UK and to quite a bit of success. “The Bohee Minstrels were a racially mixed ensemble of entertainers and for the next four or five years toured the US and Canada on their own and with Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. In 1881, they joined up with Jack Heverly’s Genuine Colored Minstrels, a group of fifty-plus entertainers, and set sail for England. The troupe returned to the US the next year, minus the Bohee brothers who remained in London and formed their own group. The Bohee brothers toured the UK extensively from Spring until Fall, and in the off-season, they manufactured banjos and gave lessons from their shop, the Gardenia Club, on Leicester Square.”

In contrast to the USA, the UK had already abolished slavery in 1833, and the 19th century saw great success for many Black people. While in the UK, the brothers made a housecall to Albert the Prince of Wales. When the brothers opened a banjo studio in London’s west end, the future King became their most famous pupil.

Little adds, “Albert the Prince of Wales would later become King Edward VII upon his mother’s death in 1901. Presumably, it was Albert who gave the brothers permission to use the moniker, the Royal Bohee Brothers.”

It’s not known how many songs the brothers wrote, but they did receive acclaim in the media.

One British newspaper, after the Bohee Brothers performed at Colston Hall said, “The greatest attraction at this Entertainment is the Brothers Bohee…among the finest banjoists of the day, and their manipulation of the popular instrument last evening proved that the reputation they have obtained has been justly accorded them…don’t fail to visit the Bohees this week”. The brothers often changed their routine playing a mix of anti-slavery and religious songs.

While growing their efforts, James fell into the role of promoting their performances while George became choreographer. Some of their well-known songs include I’ll Meet Her When The Sun Goes Down, The Darkey’s Wedding, The Darkey’s Patrol, The Yellow Kid’s Patrol, Bohemian Gallop, The Darkey’s Dream, The Darkey’s Awakening, Medley of Airs, Restless March, March in C, Hunter’s March, and Niagara March.

Banjos became a cornerstone of the growing commercial music industry in the UK, and the huge popularity of the Bohee brothers fuelled the banjo craze across Britain in particular.

In 1889 George became one of the first Black Canadians and first Black entertainer to make a musical recording. Little adds, “These were made by the Edison Bell Supply Company in Liverpool and were made on fragile wax cylinders. George went on to make at least ten recordings that year. Sadly, none of these have survived.”

Despite years of praise and success, historian Jeffrey Green reports that George Bohee's financial troubles tainted his career. A local London newspaper at the time published news about George’s debt. His meagre wages of 17 pounds per week could not support his gambling problem.

On December 8, 1897, James Douglas Bohee died of pneumonia. His remains are buried in the Great Circle of the Brompton Cemetery in London. Little tells us that the location of his grave is known but unmarked by any memorial. As for George, he continued travelling the country performing with the Bohee Operatic Minstrels, but within a year, the troupe had disbanded. George continued to perform as a solo act until at least 1905, but the minstrel craze began to dwindle as other genres became more popular. This was the end of George’s performing career and signalled the end of the Bohee Brothers’ brand. At some point, George returned to the US and lived in New York City in 1925. The exact date of his death is unknown, though a reporter recognized George in 1919 and was able to interview him for the Acadian Recorder, where he spoke of his performance for the Prince of Wales.

During the interview in 1919, George shared that they earned several hundred thousand dollars in the UK, amounting to over five million dollars today. His last words of the interview were: ‘‘Those were the days.’

By

By