Revered in the United States, this extraordinary Black Canadian artist has lingered in the shadows of his native Canada, particularly in New Brunswick, until a recent collaboration sparked a long-overdue celebration of his legacy.

Enter David Woods, founder of Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia (BANS), and the Owens Gallery at Mount Allison University—a duo determined to shed light on Bannister’s remarkable journey, 124 years after his passing.

Woods's passion for Bannister ignited when he was just 14 years old, listening to a radio program that mistakenly claimed Bannister hailed from Nova Scotia. A budding artist himself, and self-taught like Bannister, Woods felt a thrill at the discovery of this great Black artist from the Maritimes, who was pursuing art no matter the circumstances.

“I was so inspired,” he recalls, “but I quickly realized no one else seemed to know who he was.”

From that moment on, Woods became Bannister’s tireless advocate, pitching his name to galleries and art institutions throughout the 1990s. “It was astonishing,” he reflects, “to find that the art world was largely unaware of him, especially since he was celebrated in the African American community for decades.” Now Woods has successfully launched a new exhibit called Hidden Blackness, in order of Bannister's work.

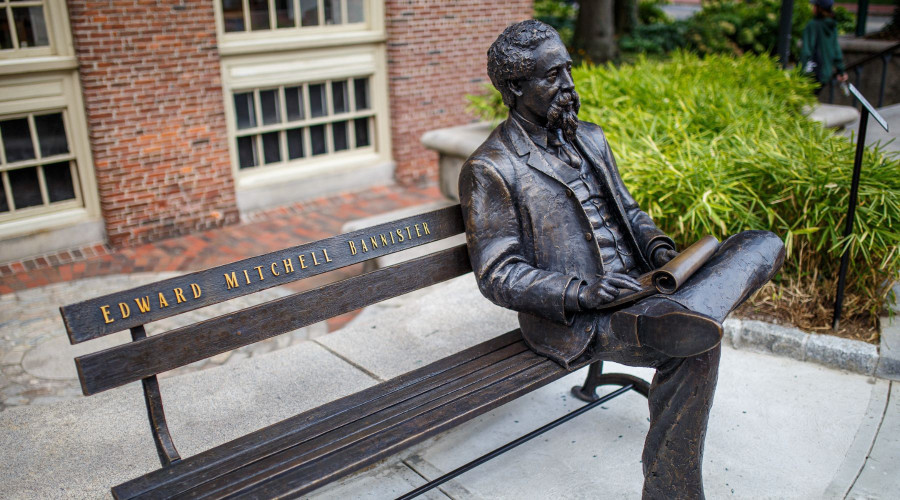

Born in a vibrant Black community in Saint Andrews, New Brunswick, Edward Bannister's path was shaped by his Barbadian heritage from his parents and a fierce determination to create.

Bannister’s father died when he was just 4 years old, leaving him and his younger brother to be raised by their mother. As a young boy, Bannister was practising to be a cobbler, but everyone around him could already see his artistic genius. Bannister himself credited his mother with inspiring his early interest in art. She died when Bannister was 16 years old. At that point, a wealthy lawyer named Harris Hatch took Bannister and his brother onto his farm where Bannister practised his art by reproducing the family’s portraits and engravings. Within 5 years the brothers had found work on ships as mates and cooks before immigrating to Boston.

It was in Boston that Bannister received his first commission for a painting. It came from a prominent African American doctor named John V. DeGrasse. This pivotal moment marked the beginning of Bannister’s ascent into the world of art, supported by those who believed in his talent.

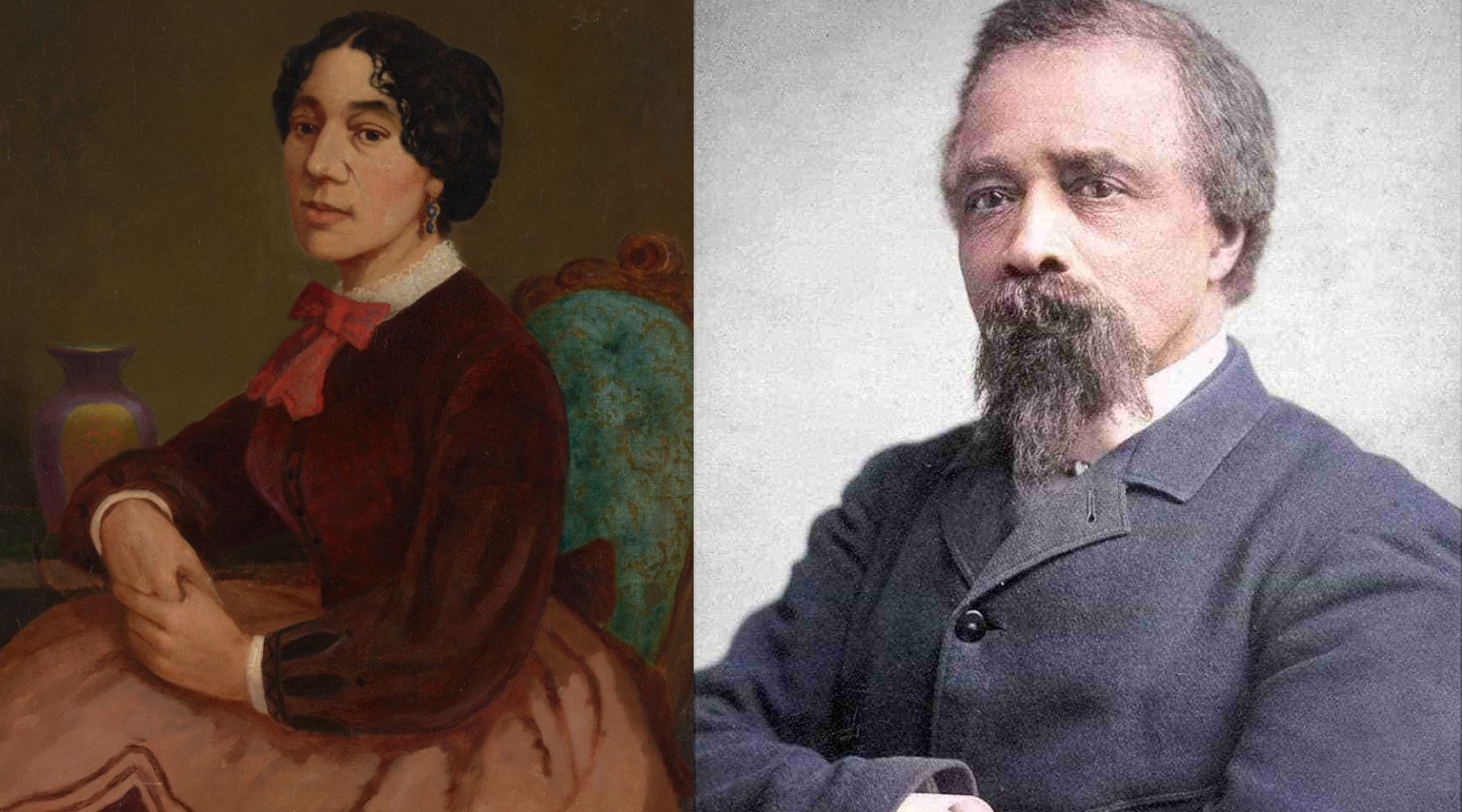

When Bannister walked into a Boston hair salon applying for work as a barber, he met the owner and the woman who would become his wife, Christiana Carteaux.

Carteaux was a remarkable woman of mixed African American and Indigenous descent. Together, they became fierce advocates for abolition and equality, living in a home that once served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Their activism was profound; they fought for equal pay for African American soldiers and organized relief efforts for those who had been unpaid for far too long. Amid their social contributions, Bannister remained a dedicated painter, capturing both portraits and landscapes that reflected the beauty of his surroundings.

Left: Portrait of Christiana Carteaux by Edward Mitchell Bannister, c. 1860. Right: Portrait of Edward Mitchell Bannister. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Left: Portrait of Christiana Carteaux by Edward Mitchell Bannister, c. 1860. Right: Portrait of Edward Mitchell Bannister. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

By 1869, the couple had settled in Providence, Rhode Island, where Bannister fully embraced his passion for art. Bannister was a founder and member of the Providence Art Club and was an original board member of the Rhode Island School of Design.

Bannister faced criticism for not featuring Black people in his paintings. Apart from his early portraiture work, Bannister’s paintings mainly depicted pastoral scenes featuring white people. Bannister was a tireless Black freedom advocate, but faced a sort of “double bind” many Black artists still face today; the pressure to represent Blackness while also depending on mainly white art buyers for income.

Nevertheless, he became a celebrated figure. In 1872 he won an award at the Rhode Island Industrial Exposition for his painting Summer Afternoon, and two silver medals from the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association.

Bannister had read an article in the New York Herald a few years earlier which said, "the Negro seems to have an appreciation of art" but were "manifestly unable to produce it". Bannister was on a mission to prove them wrong.

10 years after the publication of that article, Bannister caused a frenzy by winning first prize for his stunning landscape, "Under the Oaks," at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial. This made him the first African-American artist to receive a national award. Bannister intentionally submitted the painting with just a signature so that we would be judged fairly. When he showed up to collect his medal, he wasn’t allowed entry because he was Black.

According to the Smithsonian Institute, “Bannister related in considerable detail that the judges became indignant and originally wanted to "reconsider" the award upon discovering that Bannister was African American. The white competitors, however, upheld the decision and Bannister was awarded the medal. The location of the painting has not been known since the turn of the century.”

However, even the accolades and allies couldn’t shield him from the pervasive racism of the time. In 1885, he experienced the sting of racism when his work was overlooked at the New Orleans Cotton Exposition.

It was his wife Christiana’s financial and emotional support that kept him going. Bannister attributed much of his success to Christiana for her critical eye and her business sense.

In 1898 Bannister's home studio closed, and he quietly faded from the public eye. Just three years later in 1901 he died of a heart attack while attending a prayer meeting at church. Bannister had just completed two paintings the day before.

It wasn’t until recently that his story began to resurface, thanks in large part to Woods and Owens Gallery curator Emily Falvey, who met at a panel discussing Bannister’s legacy in 2018. Both were shocked by the lack of awareness surrounding his work, especially given their roots in the Maritimes.

“During the pandemic, we faced numerous challenges,” Falvey recalls, “from securing loans from the Smithsonian to coordinating with conservators for the installation.” But every hurdle was worth it when they finally unveiled Bannister’s work at the Owens Gallery, setting the stage for a tour across the Maritimes.

David Woods, founder of Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia points to one of Bannister's paintings "Approaching Storm" from the Hidden Blackness: Edward Mitchell Bannister exhibit. Photo by Gary Weekes.

David Woods, founder of Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia points to one of Bannister's paintings "Approaching Storm" from the Hidden Blackness: Edward Mitchell Bannister exhibit. Photo by Gary Weekes.

Woods chuckles at the guilt he’s playfully imparted on other galleries for not recognizing Bannister sooner. “It’s essential to broaden the understanding of who he was and what he achieved,” he insists. After the exhibit tours New Brunswick, it will journey to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, culminating in a publication that aims to further illuminate Bannister’s contributions.

Woods passionately underscores the theme of erasure that often shadows Black achievers. “Communities like Africville in Nova Scotia and the one in St. Andrews have been disregarded,” he explains, noting the struggles faced by Black artists historically. “For too long, they’ve been seen as outcasts, their contributions undervalued.”

Woods goes on to add that, “You were not real to [white people] in that sense, except when they needed you to look after their children or clean their houses.” Ignoring Black achievers is part and parcel of being within an oppressed community, Woods adds, saying this ignorance is deep in the Maritime and Canadian psyche.

Untitled (sunset with quarter moon and farmhouse) by Edward Bannister. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Untitled (sunset with quarter moon and farmhouse) by Edward Bannister. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Yet, Bannister stands as a beacon of resilience, defying the very stereotypes that sought to diminish him. “He was an untrained orphan with a fierce ambition,” Woods states with conviction. “To win the most prestigious art prize in America just ten years after emancipation—what an incredible statement against the beliefs that Black people were incapable of culture or art!”

Falvey hopes that audiences will not only appreciate Bannister’s landscapes but also recognize the presence of Black lives in the spaces he painted, even if they’re not depicted in the artworks themselves. Some of the earliest pieces on display may even date back to his origins in Saint Andrews, a poignant reminder of his beginnings.

For Woods, this exhibit represents the fulfillment of a childhood dream—a chance to reconnect with the past. “I hope that young artists discovering Bannister will find a sense of roots,” he reflects. “Too often, Black artists feel detached from their heritage. Bannister’s journey shows them they are part of a continuum, a legacy of creativity that spans generations.”

As the exhibit unfolds at the Owens Gallery until April 6, 2025, and beyond, it serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of recognition and the enduring impact of Edward Mitchell Bannister—a true pioneer whose story is finally being told.

The Hidden Blackness exhibit is at Owens Gallery in Sackville, New Brunswick until April 6th 2025 before going to Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown, PEI and Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

By

By