There was no place where I could sit with the fullness of my Blackness, where I could feel both seen and valued beyond struggle narratives.

Now, as a mother and School Council Chair, I find myself facing the same silences, the same gaps, the same dismissals that I encountered as a child. Black History Month often feels like an afterthought, unstructured, disconnected, and lacking the co-creation of Black voices.

I need our history to be honoured with the same depth and care as other histories. I need our stories to exist beyond civil rights struggles and adversity. I want my daughter to know that she comes from a lineage of artists, healers, visionaries, mathematicians, and philosophers. That she is more than resistance, she is also creativity, joy, and possibility.

Returning to university has illuminated just how deep these erasures go. The more I study, the more I see how our current education system subtly but powerfully dehumanizes Black learners. It is in the way narratives are framed, in the omission of our voices, in the unspoken message that our knowledge, our ways of being, are secondary. And that is something I can no longer accept.

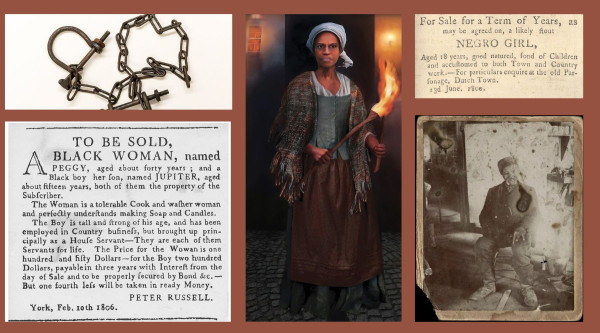

Moments That Have Felt Harmful

I recognize that harm is inevitable in life; however, in my mindfulness teaching, I embody harm prevention, harm reduction, and harm recovery as a best practice. These principles also guide my approach to education, ensuring that learning environments foster safety, healing, and transformation rather than perpetuating harm. By centering these values, we can create educational spaces that empower students, nurture curiosity, and encourage critical engagement with history.

I do not always see this approach widely embraced within learning environments and the school system. When I ask my daughter about Black History Month at school, her response is unremarkable. "We didn’t really do anything," she says, or, "I don’t remember." It stirs something deep in me, the longing for her to feel a sense of belonging and recognition, to know that her presence in this world is significant.

Then, there are harmful misinterpretations. I once overheard a child in my extended family share that at school, white students were asked to apologize to them for slavery. No context. No deeper discussion. It was just an empty exchange that left this young Black child walking away with confusion rather than understanding.

Another time, a child was given a colouring page of Martin Luther King Jr., with the simple prompt: “Why were Black people slaves?” That was the depth of the conversation. Not the resilience of our people. Not the societies we built before colonization. Not the rich cultures, languages, and traditions that continue to shape the world. Just slavery.

READ THIS: Growing up, Black History Month Felt More Like White Cruelty Month

Traditional lessons on Martin Luther King Jr. often follow a predictable pattern: students are given a brief overview of his role in the Civil Rights Movement, shown his "I Have a Dream" speech and sometimes asked to colour a picture or write a reflection. While well-intentioned, this approach fails to foster real learning. Paulo Freire describes oppressive pedagogy as a system in which students are treated as passive recipients of knowledge, rather than as active co-creators. In this model, MLK becomes a static, sanitized figure, reduced to a dream rather than engaged as a full human being with a complex history, radical ideas, and a family who shaped and supported him.

Rather than beginning with an overview of MLK’s activism, invite students to consider:

- What does it mean to stand up for what is right?

- Have you ever seen someone challenge unfairness in a way that inspired others?

- What do you know about MLK beyond "I Have a Dream"?

These questions allow students to engage with MLK’s legacy in a way that connects to their lived experiences.

Instead of solely focusing on MLK as a civil rights leader, educators can introduce his economic and labor rights advocacy, which are often overlooked in traditional curricula. Or his critiques of capitalism and militarism, which were just as central to his message as racial justice.

Instead of seeing history as something to be memorized and set aside, we can encourage students to see history as a living, evolving force. Teachers could be asking:

- What issues today would MLK speak about if he were alive?

- How does economic justice connect to racial justice?

- Who are today’s civil rights leaders, and what lessons can we learn from them?

The Emotional Toll of Advocacy

When I have tried to make suggestions like this, with detailed ideas for change, I have often been dismissed as "difficult" or "too much" simply for asking that our history be taught with integrity. I have been met with silence, resistance, and superficial agreements that never translate into action. Advocating for inclusive Black history education is exhausting.

Advocating for historical integrity often comes with frustration, sadness, and exhaustion. I long for curiosity over defensiveness, for dialogue that fosters true understanding and collaboration. At the core, my needs are for safety, growth, community, and connection.

And yet, I keep showing up. I keep speaking up. Because my daughter’s sense of self is at stake. Because every Black child’s self-worth is shaped by what they see, hear, and experience in classrooms.

The Impact of Learning and Re-learning

My journey as a mother, mindfulness educator, and student has made me deeply aware of the importance of psychological safety. I see so clearly now how Black History Month often centers on the education of non-Black people rather than the empowerment of Black students. It is performative in ways that feel extractive rather than liberatory.

Studying Pedagogy of the Oppressed gave me the language for what I had long felt but struggled to name. Traditional education treats students as passive recipients rather than co-creators of knowledge, just as Black history is often presented as something that happened to us, rather than something we have shaped.

I want Black children to experience education as a space of possibility, not a burden.

Instead of performative Black History Month activities, we need fundamental curriculum changes that center Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Indigenous, and continental African perspectives.

What We Can Do Next

A step toward this is implementing resources like Parents for Diversity’s Periodic Table of Black Canadian History, which provides a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of Black contributions across various fields. Schools must also engage in co-creation with Black educators, organizers, parents, and students through professional development, workshops, and interactive learning experiences.

True social change emerges through collective action rooted in care, mutual support, and a shared vision for transformation. By fostering dialogue and building relationships, we can co-create educational spaces that honour Black history beyond performative gestures. If we continue with temporary, surface-level fixes, we will struggle to stay afloat instead of addressing the root causes of the issue. But if we push for systemic change, if we demand a better-designed educational model, then we can create classrooms where Black students feel seen, heard, and valued every day.

I hope schools will recognize that how we tell history shapes how Black children see themselves and their place in the world.

By

By