White was the first Black Canadian concert singer to win international acclaim despite impossible odds. However, like many Black artists, she never received much praise while alive.

The Canadian Opera Company will celebrate her life and legacy in their new opera, Aportia Chryptych: A Black Opera for Portia White.

White was the third of 13 children born to Izie Dora (White) and William A. White. Her patriarchal grandparents had been enslaved in Virginia and her maternal grandparents were Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia. White sang at the school choir at six and was already singing the soprano from the opera Lucia di Lammermoor by age eight.

Driven to become a professional singer, White would walk 16 kilometres weekly for her music lessons. After finishing teacher training, she became a schoolteacher for Black Nova Scotian Communities such as Africville and Lucasville.

{https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkdxt3gljCk}

In the 1930s, White began singing competitively and studied under Bertha Cruikshanks and Ernesto Vinci. By the 1940s she’d given recitals at several Maritime universities. Though she resigned from teaching in 1941 to pursue doing musician concerts as a contralto, racism impeded her from getting many bookings despite her talent.

The high point of her career happened in the U.S. with a widely acclaimed recital at New York’s Town Hall on March 13th, 1944. She was the first Canadian to perform there. That same year, a small group formed the Nova Scotia Talent Trust to help White concentrate on her professional career. It's been running ever since, and according to their website, the Talent Trust is "a registered charity funded by government, corporations, foundations, and private donors, with the exclusive aim of propelling the next generation of Nova Scotia’s artists."

White performed music in Italian, German, French and Spanish alongside English pieces, and her three-octave range attracted wide critical acclaim. Throughout her life, she also had a son, whom she gave up to a maternal relative. Jimmie Gray's son Kevin Gray had this to say about his grandmother in a 2018 interview with Ron Fanfair:

“I figure that having a child wasn’t one of those things that she was planning on at the time. My dad is very proud and never talked about his upbringing and his biological mother. I am getting the idiosyncrasies of his relationship with her from people like Sheila White – Portia’s niece -- and her late mother, Vivian, who kept in contact with my father.”

In 1945, White signed with Columbia Concerts Inc., the largest artist agency in North America and toured both sides of the border with Columbia Concerts. Unfortunately, following a tour of Central and South America in 1946, she began experiencing vocal difficulties and problems with her management.

In 1948, White resumed touring in the Maritimes and even sang in Switzerland and France, but soon retired from public performance. In 1952, she moved to Toronto to undertake further studies at the Royal Conservatory of Music. She would sing sporadically, most notably before Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip at Charlottetown’s Confederation Centre of the Arts on October 6th, 1964.

White’s final public performance occurred in July 1967 at the World Baptist Federation in Ottawa.

Portia White died of cancer on February 13th, 1968.

{https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyDDdzMnoZo}

In an interview later in life, White explained that her love of music and performing had developed early: “Nobody ever told me to sing; I was born singing. I think that if nobody had ever talked to me, I wouldn't be able to communicate in any other way but by singing. I was always bowing in my dreams, singing before people and parading across the stage as a very little girl.”

Though we can’t know for sure, we can assume that White's international acclaim was bittersweet while she struggled for similar recognition in her home country at the time.

In 1995, White was named a “person of national historic significance” by the Government of Canada. Further legacy includes The Portia White Prize, which the Nova Scotia Arts Council awards yearly to an outstanding Nova Scotian in the arts. The award's inaugural recipient in 1998 was White's great-nephew, writer George Elliott Clarke. The Nova Scotia Talent Trust presents the Portia White Scholarship Award to exceptional vocalists. It also named its annual gala concert in her honour. At the East Coast Music Awards in 2007, White was posthumously awarded the Dr. Helen Creighton Lifetime Achievement Award.

Clarke, a former Poet Laureate of Toronto and Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate, was eight years old when White passed away. He's also written a biographical poetry novel, Portia White: A Portrait in Words, in which he recounts her life and struggles as he imagines they would have been through poetry. Clarke's parents and grandmother always talked highly of White and listened to her pupil Lauren Green from Bonanza on the radio. “I still remember we'd go up to my grandmother's place, and all the time, she'd bring out the photo album with all these black and white pictures of Portia. ‘Here she is in New York. Here she is in Toronto. Here she is doing a tour of South America in 1946’.”

Clarke describes White as a cultural ambassador for Nova Scotia who was as prolific as the Bluenose on the dime and perceived as a tourist draw to the province.

He adds that many of the issues surrounding the growth of her career came from the fact that Columbia Records never recorded her work. “I still don't understand why Columbia Records did not record her. I think the reason was that they didn't know how to sell her as a Canadian, as a ‘coloured Canadian’ singer, even though she was based for some time in New York.

She never gave up her Nova Scotian identity and, along with that, her Canadian identity. "It's difficult for Canadians, for Black Canadians, to be accepted by Black Americans, especially if they insist on being seen as Canadian.” At the time White also had a rival for the spotlight in Marian Anderson, an African-American opera singer whom Clarke describes as being part of the Civil Rights Movement before the movement had even begun. White could not have stood up against prejudice in the same way as her work was often government-funded.

It’s also important to note that Black Operatic roles were rarely offered. “This was still at a time when Black opera singers were not given proper access to mainstream opera stages. While a few stars could be on the Metropolitan Opera stage in New York and at the Met or on Broadway, it was very difficult for the majority of Black singers. It was still the Chitlin Circuit idea. Black singers perform at the lower-end, low-scale performance venues, which are oriented towards a Black public which itself was not necessarily interested in hearing the opera when they might prefer to hear rhythm, blues, jazz, and so on.”

Clarke says many of his relatives “embodied the possibilities and the perils of being Black in the first half of the 20th century.”

“Why should I write about her? She emerges as the first Black artiste of us, the Africadian people, of historical Black Nova Scotia. I will say that I try to think about her simply as a human being, as someone who was given a great gift, as someone who at the same time had that great gift but had to struggle to have it recognized and who ultimately did make a difference even though she didn't receive the accolades that she should have received.”

Aportia Chryptych: A Black Opera for Portia White, created by Canadian director and librettist HAUI and Toronto and New York-based composer Sean Mayes, aims to reclaim Portia White's story by addressing the erasure of her history.

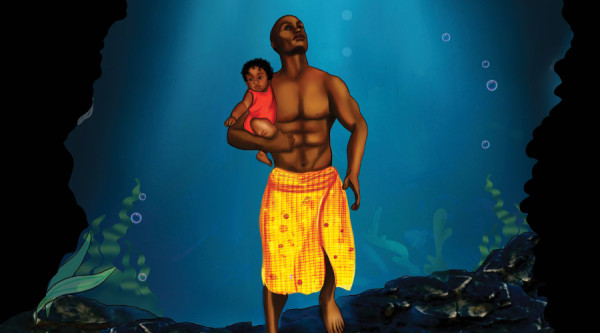

HAUI shares, “What a poetic justice to share Portia’s story in the art form that rejected her in her lifetime. And, in sharing this, to be presented by the largest opera company in Canada - talk about justice!” HAUI adds that the opera is not a biopic as it explores the spirit realm White was thrust into after death. “She's fractured into her body, her soul, and her spirit. And it ends up being a navigation of the intermediate realm, and how Portia must learn to let go of her earthly bonds in the hopes of ascension.”

Neema Bickersteth, SATE and Adrienne Danrich play White’s body, soul, and spirit, respectively, as they share with the audience the importance of White’s history to Canadians and how she might have dealt with the trials and tribulations of her life.

A free livestream of Aportia Chryptych: A Black Opera for Portia White airs June 15th. To learn more visit https://www.coc.ca/productions/24407

By

By