She won.

There are few Canadians who don’t know about Martin Luther King Jr. And yet there are very, very few Canadians who know the name of Gloria Baylis. Gloria’s victory might have been quieter, but her legacy is no less significant.

In Halifax, where her daughter Françoise Baylis (a member of the Order of Canada) works as a bioethicist, recent news of an explosive ruling about racism at Halifax Transit shows that more than 50 years after Gloria first challenged racial discrimination, Black people are still fighting the same battles using the same legal avenues.

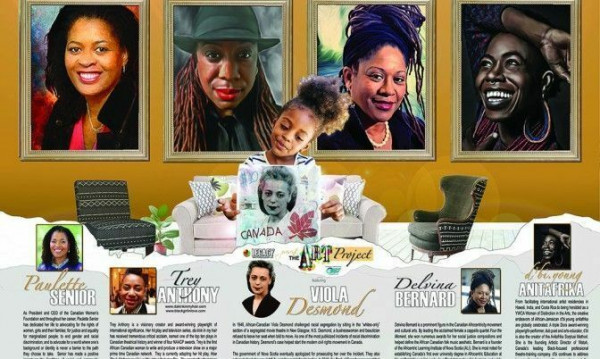

In the last few years, due largely to the efforts of her sister Wanda Robson, Viola Desmond has become a civil rights icon in Canada. Viola’s image is on the soon-to-be released $10 bill, and we can now walk on streets named after her. But for a long time before that, Viola’s story was unknown and ignored outside of the African Nova Scotian community.

We now celebrate Viola Desmond, but the stories of other heroic Black women who led the struggle for human rights in this country are forgotten. Like Viola, Gloria took her case to court and persevered through long years of injustice.

So who was Gloria Baylis?

Born in Barbados, Gloria trained as a nurse in England. In a move that suggested the fearlessness she would later show, as a teenage girl she saw an ad in the back of a book encouraging women to start a career in nursing; without telling her parents, she applied. When she was accepted, her parents had no choice but to allow her to go.

Before she even left Barbados, when she was 16 years old she fought an employment case, demanding fair wages. Not only was she still a young girl when she stood up to her employer; additionally, this was in a colonial country still under British rule. Gloria would show this kind of courage throughout her life.

She emigrated to Canada in 1952. Before changes to the Immigration Act in the 1960s that removed bias against non-white immigration, only highly qualified Black immigrants were granted entry to Canada.

Gloria began her career in Canada working in hospitals. But after difficult pregnancies and with young children, she was looking for a position that would allow her to work part time and to ease back into the workforce.

The Queen Elizabeth Hotel seemed like the perfect place.

A large hotel owned by the Hilton chain, the Queen Elizabeth was advertising for a nurse to assist the guests. Gloria decided to apply for the position, planning to split the hours with a white friend. They agreed that they would both go to the hotel and submit an application.

When Gloria went, however, she was informed the position was filled. She thought nothing of it until her friend called to ask her if she had applied. When Gloria told her friend that she had tried earlier in the week but the hotel had already hired somebody, her friend was surprised. After all, she had just returned from handing in her application.

It was then that Gloria realized that her application was refused because she was Black.

In 1964, the Quebec Act Respecting Discrimination in Employment was passed. It was the first piece of legislation in Canada to define discrimination, and the first that explicitly made reference to race. The Act came into effect on September 1, 1964. It was on the following day, September 2, that Gloria Baylis went to apply for the job at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel.

Gloria was a highly qualified nurse who had been in charge of managing other nurses. Not only did she speak English and French, she also was an expert at sterilizing medical instruments, an important asset at a time when these tools were reused. She was outraged at this obvious injustice, not only for herself, but for the growing community of Black immigrants. Gloria realized that she was a test case for employment discrimination, and with the support of the Negro Citizenship Association, she filed a complaint under the new Act.

The case began in 1965.

Brought to court, the hotel denied any discrimination had taken place. They argued that Gloria was rejected because she was not qualified, and because she did not speak French. Proven wrong on those points, they argued that they couldn’t be discriminating based on race because they had no idea that Gloria, a light-skinned woman, was Black!

This led to a key moment in the case.

Called onto the stand, Gloria’s lawyer asked her directly: “Are you a Negro?” “Yes,” declared Gloria. “I am a Negro!”

Françoise Baylis recognizes this statement as a “political act” by her mother. As a woman from Barbados, she would not have used that language — from the United States — to describe herself. But, as she knew, the case hinged on that public claiming of her race, and of her visible Blackness.

To understand the significance of this statement, we can turn to Frantz Fanon’s 1952 essay, “The Fact of Blackness,” which opens with the words “Look, a Negro!” These words describe how Fanon experiences his Blackness through the eyes of white people — the fear and disgust white people feel, and dehumanization experienced by Black people. For Gloria to announce that she was a Negro in court was to openly claim her Blackness and to show that her race was not a source of shame, but a site of pride.

In October, 1965, Gloria won her case. In an published article in the Star, the judge was quoted saying that “Mrs. Baylis had been treated differently from other applicants who had been told they would be interviewed. Mrs. Baylis was told only that the job had been filled.” The prosecutor, Gerald N. Charness, said the case was “without precedent, not only in Quebec but also in the entire country.”

But the case didn’t end there. The hotel was fined $25. They refused to pay.

Over the next 11 years, the hotel fought the ruling, even considering seeking leave to have the case heard in the Supreme Court. Astonishingly, the lawyers stopped arguing about whether or not the hotel was racist, and instead made the argument that Gloria had no right to bring the case under the Discrimination Act because the Act itself was unconstitutional and should not have been passed!

This is what happens when a Black woman asserts her rights.

Finally, in 1977, 12 years after she had first brought the case to court, the original conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeal. As Gloria’s biography in Black in Canada notes:

This decision stands as a moral victory for all Black people in Canada, and is a testament to Gloria’s tenacity and willingness to stand up for her rights regardless of the circumstances.

It was only then, when media showed up at the house to photograph Gloria for the papers, that her children found out that she had been fighting in court all these years. Gloria had protected her children from knowing about the case, and had continued to work and raise her family, all while the hotel dragged her from court to court to avoid paying such a small fine.

Gloria’s accomplishments do not end with her victory in court. At her kitchen table, she started a small medical instruments company. Françoise remembers helping to wrap the instruments which her brother would drive to deliver.

That company, Baylis Medical Company, has grown into a leading developer and manufacturer of medical products, employing hundreds of people.

Gloria Baylis’ four children are all incredibly professionally successful. Frank Baylis is currently an MP representing the riding of Pierrefonds-Dollard in the House of Commons, and Françoise’s sister is a medical doctor, while her other brother holds a PhD in social work. But more than professional success, they all believe in an ideal of service to others, a value instilled in them by their mother. Says Françoise:

I think what makes you successful is having those strong core values and being brought up to believe that you have to use your talents not just for yourself but for others. And I think when you’re using them for others it gives you that extra push because there’s no sense that this is about me and it’s selfish, it’s about making the world a better place.

So then you can bear all kinds of setbacks because you’re working for a cause. It’s amazing what people can put up with when they’re working for a cause — things they wouldn’t put up with if they thought they were just working for themselves.

Gloria is remembered as a woman who would very literally take the shirt from her back and give it away. She is beloved as a woman who took into her house children who needed a place to stay, who sat at the bedsides of the sick, and who worked tirelessly for others. She believed that when community sticks together, it can accomplish amazing things.

At a recent event, a friend tells me, Françoise was on a panel. In question period, an audience member asked what experience the panel members had in thinking about issues of race. After the other speakers addressed the question, Françoise spoke. I might pass as white, she told the audience, but I claim my Blackness. And I claim it because my mother fought and won the first case of employment discrimination based on race in Canada. “Yes, I am a Negro.”

When we look at the human rights case brought against Halifax Transit, we can see many parallels with Gloria’s case. In both cases it took 12 years to get any kind of justice. And as in Gloria’s case, lawyers argued everything they could to prevent a ruling acknowledging racism. This is why knowing about Gloria Baylis is such an important part of Canadian history as we go through the same struggles over and over again.

And yet, the transcripts from Gloria’s case have disappeared. Her daughter Francoise has searched through archives, through court records, contacted law firms, checked with universities – but the transcripts have been lost. What remains are newspaper accounts, and quotations from the original ruling in judgements as the case wound its way through appeal. The first case in Canada to address racial discrimination, and the record is largely gone.

And so, even as people fight to preserve the names and statues of men like Edward Cornwallis, the history of Black women in this country disappears, and is forgotten. Without Gloria’s children speaking about her, her story would have been lost to us with her death in 2017.

When we pay with the new $10 bills, we should ask ourselves every time: what other Black women should I know about? What other Black women sacrificed, and struggled, and fought injustice? Who else has been erased, is not being taught, or has not been recognized?

Gloria Baylis is another Black women we should all honour. And there are many, many more.

This article originally appeared in The Halifax Examiner.

By El Jones

By El Jones