R v Desmond

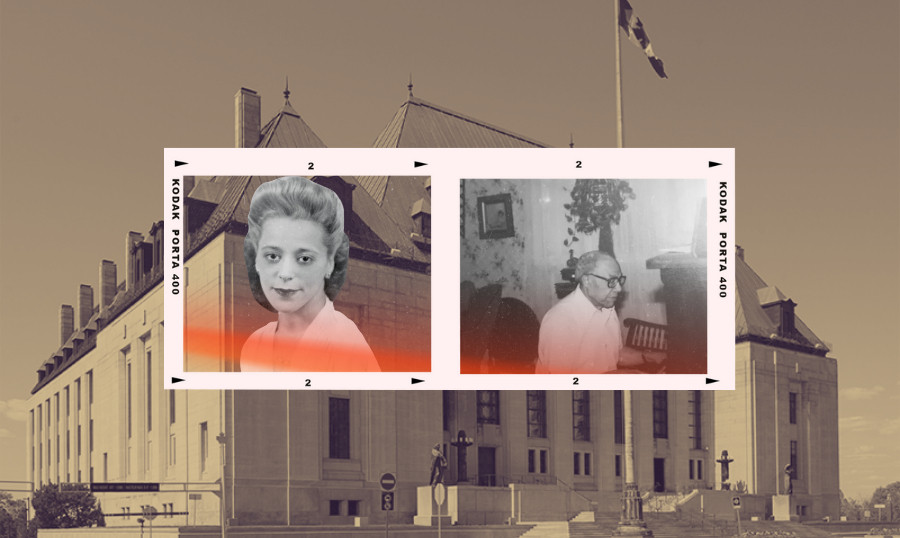

On November 9, 1946, Viola Desmond, a successful Black businesswoman, was convicted for not paying the appropriate tax for a ticket at the Rosalind Theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. At the time, Black people had to sit upstairs and were charged 30 cents for a ticket. White people were charged 40 cents and sat downstairs. There was also a tax imposed by law of three cents for a downstairs ticket and two cents for an upstairs ticket. Ms. Desmond, in protest of the discriminatory policies, wanted to sit downstairs. It is not clear from the decision if Ms. Desmond attempted to pay the difference in the ticket price to sit downstairs but was unable to do so because the ticket agent wouldn’t accept the money from her. What is clear is that she disregarded the ticket agent, sat downstairs, and refused to go upstairs.

She was criminally charged because she failed to pay the difference in the tax between the two tickets. In other words, she was charged for tax evasion for failing to pay 1 cent. Ms. Desmond was jailed and fined. She then started a Court proceeding to quash her conviction, which was appealed to the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal. But her conviction was upheld, largely for procedural reasons.

Even though the judge felt he had to uphold the conviction, he also felt it was unjust and made that clear in his ruling when he said, "Had the matter reached the Court by some method other than certiorari (an appeal), there might have been an opportunity to right the wrong done this unfortunate woman. One wonders if the manager of the theatre who laid the complaint was so zealous, because of a bona fide belief there had been an attempt to defraud the Province of Nova Scotia of the sum of one cent, or was it a surreptitious endeavour to enforce a Jim Crow rule by misuse of a public statute."

Ms. Desmond passed away in 1965. In 2010, the province of Nova Scotia granted an official apology to Ms. Desmond and a free pardon. Ms. Desmond now appears on the 10-dollar bill.

Christie v York

Fred Christie was a Black man who entered a tavern in Montreal and requested a glass of beer in the late 1930s. The staff at the tavern refused to serve Mr. Christie because they were instructed not to serve Black folks. Mr. Christie started a lawsuit against the tavern for damages due to the humiliation that he suffered.

At trial, Mr. Christie was awarded $25 in damages. The trial judge decided that it was illegal for the tavern to refuse to serve Black people because of provisions in the Quebec License Act, which licensed the sale of alcohol. But this decision was overturned on appeal. Mr. Christie then brought his appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The majority of Supreme Court of Canada judges agreed that generally speaking, a merchant in Quebec has complete freedom of commerce and may deal with any individual member of the public as he sees fit unless a law provides otherwise. The License Act provided that a restaurant could not refuse to give food to travelers without a good reason. The Court decided that Mr. Christie was not a traveler, and the tavern was not a restaurant. Thus, it was legal to refuse service to him due to his race on the basis of freedom of commerce. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled against Mr. Christie and upheld the decision to dismiss his lawsuit.

But one of the judges, Justice Davis, disagreed with the majority of his Supreme Court peers. He stated that the tavern was granted a special license to sell liquor, which was governed by statute, and it was incumbent on the government to set any restrictions on the sale of liquor on the ground of race or faith. Justice Davis said he would have ruled in favour of MR. Christie and allowed him to keep his $25. in damages.

Around the time these decisions were decided, public opinion was starting to change. In 1944, Ontario passed its first piece of legislation based on anti-discrimination, the Racial Discrimination Act. This Act prohibited posting or publishing any notice, sign, or symbol which had the intention of discriminating against any person because of race or creed. Unfortunately, this Act wasn’t particularly effective and discrimination remained common. However, further human rights legislation continued to be passed, culminating in the Ontario Human Rights Code in 1962.