He was the founder of multiple organizations, which include the Jamaican Canadian Association, Urban Alliance on Race Relations, Black Business and Professional Association, National Council of Jamaicans and Supportive Organizations.

He also has been the recipient of many awards, including the Order of Ontario, the Order of Canada, the Order of Distinction (Jamaica) and an Honorary Doctor of Law (York University). In 2004, the Toronto and York Region Labour Council established an annual award in his name.

He published a newspaper (The Islander), served on the Ontario Human Rights Commission, and was an Adjudicator with the Ontario Labour Relations Board.

He was an amazing athlete. He used to box, swim, run, and play soccer. He was one of a kind, and he will be greatly missed by many. Here is a look back at his life and legacy, courtesy of Lorne Foster at the Canadian Encylopedia.

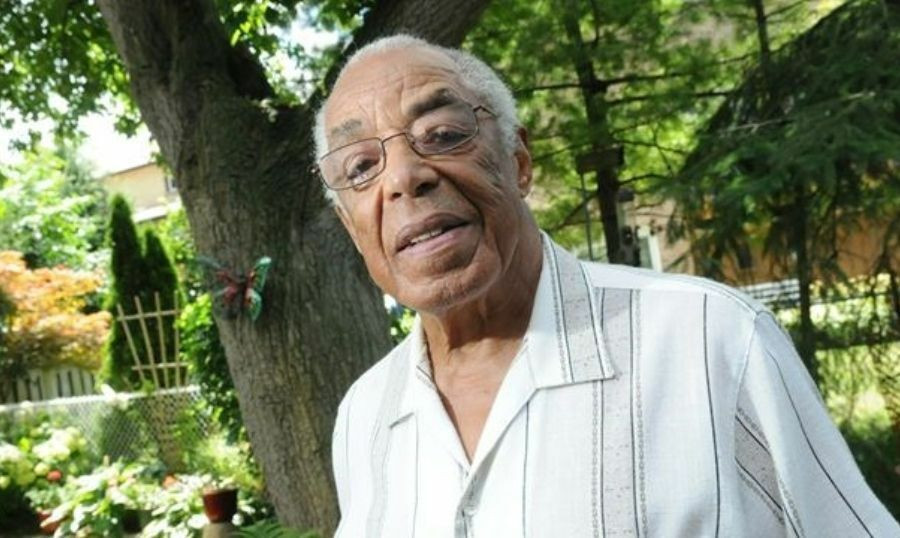

Bromley Armstrong was a pivotal figure in the early anti-discrimination campaigns in Ontario that led to Canada’s first anti-discrimination laws. A self-described “blood and guts” ally of the working poor, Armstrong demonstrated a lifelong commitment to the trade union movement and the battle against disadvantage and discrimination. For more than six decades, Armstrong worked for human rights, helping to generate civic and government support for racial equality and advocating for human rights reforms in public policy.

Family

Bromley Armstrong was born in Kingston, Jamaica, into a family with strong roots in the working class and passionate ties to the labour movement. He was the fourth of seven children (the other siblings were Esmine, Eric Jr., Everald, Olive, George and Monica). Armstrong was born at a time when the political atmosphere in Jamaica was rampant with the call “Better must come.” His parents, Eric Vernon and Edith Miriam Armstrong (née Heron), instilled a strong work ethic and love of athletics that supported Bromley throughout his life.

Migration to Canada

Following the Second World War, a young Bromley Armstrong and his brother George decided to emigrate to Canada in search of education and employment. The economic hardships of the Great Depression and the untold human costs of the Second World War had left Jamaica in a state of turmoil, and employment opportunities were scarce. On 11 December 1947, Bromley and George boarded a plane at the Kingston airport bound for Toronto (via Miami; Washington, DC; Chicago; and Buffalo). They arrived two days later at Malton airport, which was later renamed Pearson Airport.

Trade Unionist

Motivated by his parents’ example of hard work and community involvement, Bromley Armstrong aspired to success in his new home of Canada. Although he initially had difficulty finding work, he was eventually hired by Massey-Harris (later Massey-Ferguson), an agricultural equipment manufacturer. As Armstrong wanted to be a welder like his father, he enrolled in the Chicago Vocational Training School, attending classes during the day while working at Massey-Harris at night. Armstrong became a member of the United Automobile Workers (UAW) Local 439 and soon became a leader in the Canadian trade union movement, toiling as a shop steward to improve conditions for industrial workers.

Social and Human Rights Activist

In addition to his work as a trade unionist, Bromley Armstrong was committed to community-based social action. He founded many organizations, including the Urban Alliance on Race Relations, Black Business and Professional Association, Canadian Ethnocultural Council, Jamaican Canadian Association, and National Council of Jamaicans and Supportive Organizations in Canada. He has also served on the Ontario Human Rights Commission, Ontario Labour Relations Board, Toronto Mayor’s Committee on Community and Race Relations, Ontario Advisory Council on Multiculturalism, and Board of Governors of the Canadian Centre for Police-Race Relations. However, Armstrong is probably best known for his involvement in the “Dresden story” and the Toronto “rent-ins” of the 1950s and 1960s.

The Dresden Story

Although racism was not officially entrenched in Canadian society in the 1950s, in many ways its “unofficial” character made it much more difficult to navigate than in the United States, where segregation was the law in several states. Nowhere was this more dramatically revealed than in the history of Dresden, Ontario, a small, nondescript town close to the US border.

In the 19th century, Dresden was the home of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (see Josiah Henson) and the terminus of the legendary Underground Railroad, which brought refugees from enslavement in the United States to the promise of freedom in Canada (see also Black Enslavement in Canada). By the end of the Second World War, Blacks constituted close to 20 percent of Dresden’s inhabitants, but several restaurants and barbershops habitually refused to serve them. The irony of Dresden, Ontario — once a beacon of hope for Black people — turning into a bastion of racism wasn’t lost on early human rights activists.

Since 1948, the National Unity Association (NUA) of Chatham, Dresden and North Buxton had been fighting for social justice and racial equality. The work of the NUA led to groundbreaking legislation that prohibited discrimination in hiring (the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1951) and in housing and public places (the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1954) in Ontario. However, they were less successful in persuading the Dresden town council to end discrimination against Blacks (see Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada).

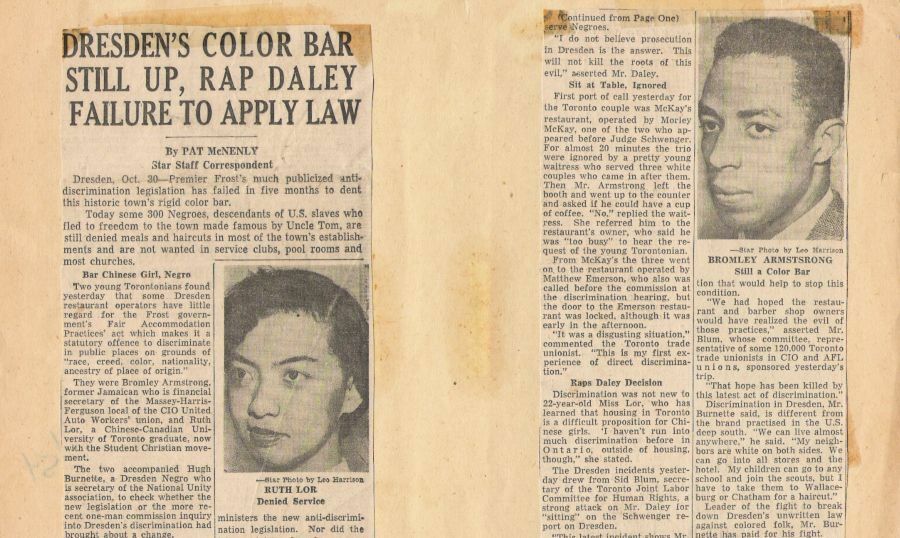

Bromley Armstrong participated in “sit-ins” in Dresden restaurants that refused to serve Blacks. The sit-in “tests,” organized by the Toronto-based Joint Labour Committee to Combat Racial Intolerance in conjunction with the NUA, were a classic bit of revolutionary street theatre. They were conducted in the presence of invited media and became a valuable tool of resistance for members of the early human rights movement in Canada, as well as civil rights supporters in the United States. In fact, the Canadian sit-ins predated those in the US.

In October 1954, Armstrong travelled to Dresden to join the resistance activities organized by Hugh Burnett and the NUA (Burnett was the plain-spoken African-Canadian carpenter who led the local resistance against discrimination in Dresden). Ruth Lor Malloy, a Chinese Canadian who was secretary of the Student Christian Movement at the University of Toronto, and Armstrong accompanied Burnett to Kay’s Café, where they were refused service, as expected. It wasn’t the first sit-in at Kay’s Café. Indeed, the owner, Morley McKay, was so upset about the frequent “tests” that Armstrong worried he might be attacked by McKay, who was angrily wielding a large meat cleaver and appeared to be having trouble controlling his notorious temper.

Bromley Armstrong and Ruth Lor

Clipping from the Toronto Daily Star, "Dresden’s Color Bar Still Up, Rap Daley Failure to Apply Law", October 30, 1954.

(Archives of Ontario, F 2130-8-0-1). Reproduced with permission – Torstar Syndication Services.

The Dresden story received prominent coverage in Toronto newspapers and ultimately propelled the nascent rights movement to success. Reinforced by delegations to the legislature, the incident convinced Ontario Premier Leslie Frost to publicly affirm the province’s commitment to anti-discrimination laws. It also contributed to the establishment of the Ontario Human Rights Commission in 1961, the first organization of its kind in Canada and one of the first human rights commissions in the world (see also Canadian Human Rights Commission).

The Toronto “Rent-Ins”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Bromley Armstrong and Ruth Lor Malloy also pioneered the first “rent-ins” in Canada by responding in person as a couple to advertised vacancies. When they were told the rooms had already been taken, a White couple — the other half of the “test” team — would arrive and be offered the very same accommodation. Armstrong, Malloy and the other members of their team built similar cases from their visits to Toronto restaurants and “private” clubs. Their efforts helped bring many establishments to the attention of the legal system.

Later Life

Armstrong and his photographer wife, Marlene, lived in Pickering, Ontario. The couple had one daughter, Lana Mae. In his retirement, Armstrong continued to organize conferences for youth, as well as mediate conflict situations and provide guidance and counsel to individuals and organizations.

Bromley Armstrong and his wife, Marlene, admire plaque presented to him by the Jamaican-Canadian Association in 1980. Armstrong was honoured for his tireless fight against discrimination in Ontario. Photo by: Doug Griffin

Significance

From his early days as a trade unionist and active leader in United Automobile Workers (UAW) Local 439 to his later role in restructuring the National Black Coalition of Canada, Bromley Armstrong was an outspoken labour and human rights activist working diligently for progressive social change.

Awards and Distinctions

Bromley Armstrong received numerous awards and distinctions that recognized his lifelong social justice achievements, including the Order of Distinction in Jamaica, Order of Ontario, and Member of the Order of Canada (1994). In 1988, Toronto Life magazine profiled Armstrong as one of the 50 most outstanding contributors. In 1998, he was recognized with the Harmony Award as “a man who has educated individuals, organizations and communities through his unselfish and unwavering commitment to human rights, race relations and labour relations in Canada for almost 50 years.”

On 11 June 2013, Armstrong received an honorary doctor of laws degree from York University for his demonstrated dedication, passion and lifelong commitment to the battle against racism. In his acceptance speech, Armstrong said, “I see before me a gathering of wonderfully engaged and dynamic people, all poised for action. It is a pleasure to be here, not only to welcome this new generation of thinkers to the world but also to welcome what I believe is a community of activists. If you accept the role and become an agent of change, this is what you will be up against. But the rewards will be beyond measure.”

Read the original article here by Lorne Foster.

Armstrong's viewing will be Tuesday, August 28th, 2018 from 4:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. at the McEachnie Funeral Home in Ajax, Ontario.

The funeral service will take place on Wednesday, August 29th, 2018 at 11:00 a.m. at Holy Redeemer Catholic Church located at 796 Eyer Drive in Pickering, Ontario. In lieu of flowers, please make donations to P.A.C.E. Canada (pacecanada.org/donate).

By

By