The family has condemned the movie as a “symphony of lies”, prompting star Mahershala Ali to apologize to them. There was even more outrage last week when the film won best picture at the Oscars.

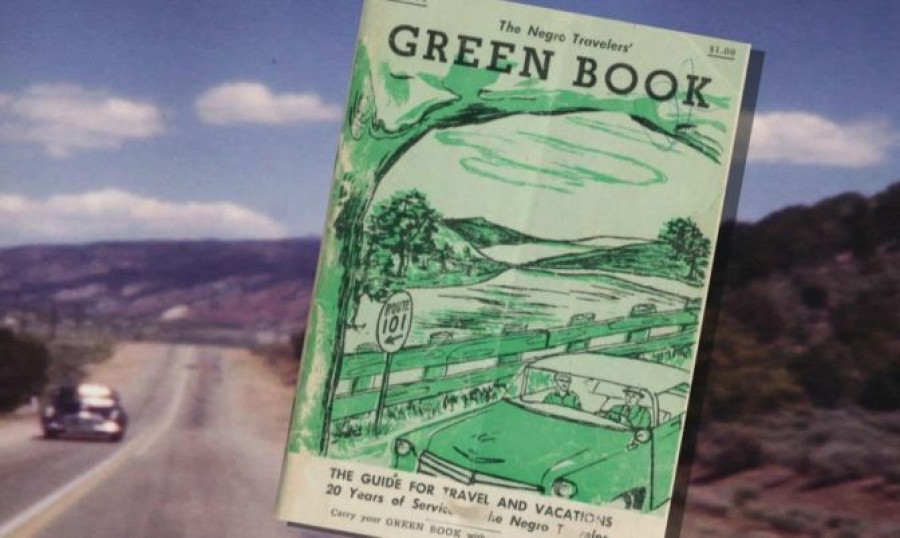

Regardless, the movie has brought recent interest in the book that gave the film its name. “The Negro Motorists Green Book” was first published in 1936 by Victor Hugo Green a Black mailman in New York City. At that time, a family road trip for a Black family was risky. Treading into the ‘wrong’ area or the ‘wrong’ establishment could be fatal. So the purpose of the book was to provide a list of hotels, restaurants, and gas stations that were willing to serve Black people.

In the first edition, Hugo writes, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal rights and privileges in the United States.”

The Green Book ceased publication in 1966 shortly after Victor's death. He left behind a powerful legacy with the Green Book being integral to conversations around segregation and discrimination in the United States.

There’s a Canadian connection here too. While the book was primarily targeted to Black Americans, the 1938 edition listed a location in Montreal. This was - as far as I could find - the first foreign location listed in the Green Book. And, as the years went on, more and more locations would be added. The 1959 edition included locations in Niagara Falls, St. Thomas, Collingwood, Harrow, and Leamington. The 1962 edition would expand to include St Charles, and Crow Lake.

Perhaps the most comprehensive list of Canadian locations was the 1966 edition which included locations with the furthest west being Saskatchewan, with Moose Jaw, Regina, and “Saskateen” (a misspelling) listed.

Some locations are interesting with the railway hotels being well represented. Perhaps their inclusion in the book is due to the prominence of Black sleeping car porters who were very familiar to Canada’s rail network.

The inclusions of these places may surprise some. However, they serve as a reminder of our history and to show Canadians that this stuff didn’t just happen “over there” but it also happened where you grew up, fell in love, or raised a family.

It is also a reminder of the segregation in Canada. Take Alberta for example - where Black Canadians were refused admission to swimming pools, theatres, bars, and even hospitals. This was a painful reality that stretched many years. And you get a better idea by looking back on the civil rights figures who opposed these policies.

Such as Charles Daniels who fought against a theatre that refused him entry in 1914 Calgary - he won his case. Or Lulu Anderson - a Black woman - who did the same in Edmonton in 1922 but lost her case. There is also the case of a group of Black families that opposed segregation in one of Edmonton’s first public swimming pools. Or Ted King, who in 1959 sued a Calgary motel for refusing him entry. He would lose his case to a loophole that would later be amended by the Alberta legislature.

These stories make the Canadian entries in the Green Book feel more real and add necessary weight to this history. A history that is often neglected and ignored in favour of presenting a rosy picture of Canada that seeks to comfort Canadians rather than to challenge us.

By learning about this history we are able to re-emphasise the importance of this history and connect it to Canada’s legacy of anti-Black racism. Furthermore, we learn more about our civil rights heroes and how they helped fight for the very rights that I have to this day.

There is still work to do but learning about the Green Book’s Canadian connection is one step.

Bashir Mohamed is a freelancer writer based in Edmonton, Alberta. He enjoys researching Alberta's history along with the modern day legacy of discrimination in the province.

By Bashir Mohamed

By Bashir Mohamed