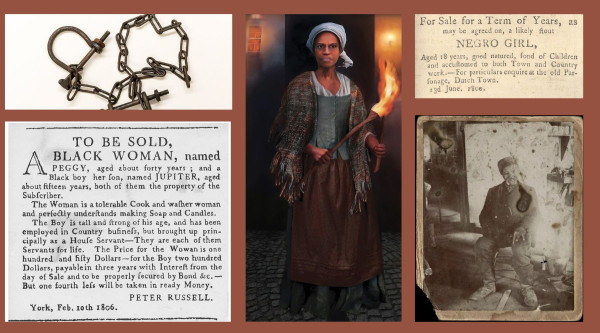

While there were four major migrations of Black people into Canada, and while those who came up to B.C. in 1858 were free people, his own ancestors came up in the 1800s as part of the rush coming to Ontario and Quebec to escape slavery.

Most of these people travelled via a system of secret alliances and shelters known as the Underground Railroad. The term came from the secret code used so information about shelters (or stations) and guides (conductors) could be spoken of with less risk of discovery.

“My great grandfather, he was a traveller on the Underground Railroad,” Nicholson said. “He and two other companions escaped from slavery in West Virginia and they made their way on foot from West Virginia through to Pennsylvania.”

For many people of Black descent, it can be difficult to find records or paperwork about ancestors since birth and death certificates were not kept for slaves. However, some abolitionists in the United States and Canada kept records of the people who came through the Underground Railroad, a move that came at great risk since aiding an escaped slave was illegal.

One of these record keepers was William Still, who kept records of Underground Railroad passengers, including where they’d come from, how much money they were given, and where they were heading.

After slavery was abolished in the States in 1865, Still published a book in 1868, under the title The Underground Railroad.

“I call it the Bible of the Underground Railroad, it’s about two inches thick,” Nicholson said. “But my great grandfather is in those records, on page 228.”

Adam Nicholson, under the alias John Winkoop, passed through a station in Philadelphia before he and two companions crossed the border into what was then Upper Canada in 1854.

Adam settled in the Niagara area, in what is now southern Ontario, and helped build a community there through farming and construction.

Records in the St. Catharine’s library tell of Adam, including records from a family that hired him to help them on their farm.

“She talks about how sad it was that he was a big strong man, he could carry 100-pound bags of sugar from the boat docks … about how he was a good worker, and it was kind of sad because he had all these scars on his back from whippings,” Nicholson said. “It was kind of emotional reading that for me.”

Adam built a two-storey home in the Niagara area, one that the Nicholson family lived in for four generations. While Nicholson didn’t live in the house himself, he recalled visiting his uncle at the home when he was a child.

“My strongest memory of it was the terrible tasting well water,” he said with a laugh.

After Nicholson moved to B.C., he took on the role as the family historian and joined the B.C. Black History Awareness Society. Since then, he’s spent 20 years sharing the history of Black Canadians to spread education of their history and awareness of their contribution to the country.

“It’s amazing how many people aren’t aware of it,” Nicholson said. “So many times people will ask me ‘where are you from?’ and I’ll say ‘Canada,’ and they’ll ask ‘No but where are you really from?’ as if I have to be from the West Indies, or I have to be from Africa. But, my family has been here since before Canada was a country … Most of the people who are asking me, their family hasn’t been here half as long as my family.”

Nicholson said that while prejudice against Black people has certainly declined, it’s paramount for newer generations to know where they’ve come from.

“I think it’s important for young Black people in particular to have positive role models, and to learn that they’ve been here as long as most Whites,” he said.

Article originally published on Sooke News Mirror.

By Nicole Crescenzi

By Nicole Crescenzi