It also seems like a sport far removed from the definition of Black Canadian culture that I have in my head. But when I came across a Black History month event happening in Ottawa called Speaking Black Hockey, I was intrigued by the idea that hockey was once full of people who looked like me, but their contributions to the sport have long been covered up.

Where was hockey invented?

Hockey in Canada is thought to have started in Windsor, Nova Scotia in 1802 and eventually spread across the country. Early records indicate that around 1815 Blacks were playing an early form of hockey amongst themselves on the frozen waters of the North West Arm area in Halifax, Nova Scotia. With the increased popularity in hockey by the 1880s, teams and leagues were formed across Canada. In Ontario, for example, in the late 1890s and early 1900s Blacks like Hipple “Hippo” Galloway, Charlie Lightfoot and Fred “Bud” Kelly played on white teams as did Herb and Ossie Carnegie and others in later years. However, in Nova Scotia, things for Blacks had changed over time. They were denied the opportunity to play on local white teams because of their race.

At the time it was a commonly held belief that Blacks could not endure cold, that our ankles were too weak to skate and we were not smart enough to understand complex hockey plays. In spite of that, we went ahead and formed our own league; the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes. According to George and Darril Fosty, authors of the groundbreaking book “Black Ice”, all Black teams started forming around 1895 and by 1900 the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes was fully formed and based in Halifax. It ended coincidentally (or not) around the same time the NHL was formed, around the mid 1920s.

“Led by skilled and educated leadership, the Colored League would emerge as a premier force in Canadian hockey and supply the resilience necessary to preserve a unique culture; a culture that exists to this day. Unfortunately, such was their fate, that their contributions were conveniently ignored, or simply stolen, as white teams and hockey officials, influenced by the Black league, copied elements of the Black style or sought to take self-credit for Black hockey innovations.” (George and Darril Fosty)

One of those innovations was created by a Colored League player, Henry Braces Franklyn of the Dartmouth Jubilees. He was a tiny goaltender who started flopping down on the ice to stop a shot. This “butterfly style” of goaltending wasn't even allowed in other leagues at the time. Twenty years later it would become the standard in goaltending. But today, the history books credit hockey’s Hall-of-Fame brothers Lynn and Frank Patrick and their Pacific Coast Hockey League, as the first individuals and league to allow goaltenders to play in this manner. No mention of Franklyn and the Colored League. Another example is Eddie Martin of the Halifax Eurekas, who was also a baseball player and is the one who really invented the “slap shot”, 25 years before Frank Cook introduced it to the National Hockey League. I had no idea there were actual names for these different styles of hockey plays, but it’s cool that Black men invented them. Not cool that they weren’t acknowledged.

Apart from their dynamic playing style on the ice that thrilled fans, The Colored League was so popular because they brought the hype! There were exciting shows during half time; with live bands and skating contests to engage the audience. It was the kind of stuff that was not being done at the white games; the kind of stuff that is now commonplace at any big sporting event. Media flocked to the games because crowds of over a thousand people were attending, including lots of white people enjoying themselves too!

So why did the Colored League come to an end just a few decades after it was born? You’ve heard of Africville right? Let me explain. The city of Halifax decided they needed large portions of land to run a railway right through Africville, basically kicking Black people out of their homes. There was of course, protest against the move. And leading the legal fight were several prominent players from the Colored League. Backlash ensued: the team stopped getting ice time. When they did, it was under very poor ice conditions. The media stopped covering the games, people stopped coming, and the league was effectively killed off, left to play on outdoor ponds. There were several factors contributing to the gradual decline of the league, including World War I and the Halifax Explosion of 1917, but the Africville issue was perhaps the most critical factor.

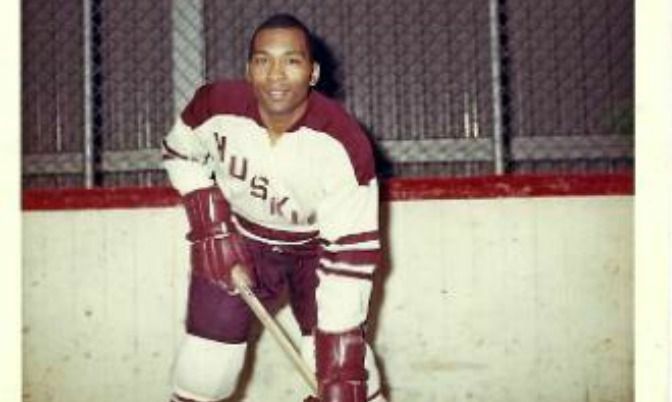

Around the same time all this was happening, the NHL was formed in 1917 and it took them 41 years to allow any Black players. New Brunswick native Willie O’Ree made his debut with the Boston Bruins in 1958. Then from 1961 - 74 there seemed to be an unofficial “lockout” of Black players. Highly skilled players such as John Mentis, Stan “Chook” Maxwell, Frank “Danky” Dorrington, and Alton White, who were languishing at the minor and semi-professional levels, did not receive or get a fair shot at making the NHL while less talented white players were advancing. Herb Carnegie is known as the greatest hockey player to never play in the NHL simply because he was Black.

Many Black players were making strides in hockey at the intercollegiate level. That’s where Bob Dawson, a student at St. Mary’s University in Halifax became the first Black player in 1967 in the Atlantic Intercollegiate Hockey League. In 1968, Bob was regarded as one of the most improved defensemen in the league. Later, Darrell Maxwell and Percy Paris joined him, making Saint Mary’s the first and only Canadian university to have three Black players on the same team. To add to that distinction the trio played on the same line in 1970 to become the first all-Black line in university and college hockey. He describes what that was like:

“Everything was ok on our own team, the guys were very respectful of us but when we got on the ice to face off with other teams, especially in Prince Edward Island, that’s where it got nasty,” says Bob. He recalls racial slurs such as ni**er, coon, spook, snowball and monkey being hurled at him during play. Added to that were the dirty tricks, such as a whack behind the legs with a hockey stick and getting your feet knocked out from under you. "White people it seems had a perception that hockey was a white man’s sport, and Black people should stick to sports like basketball or baseball,” says Bob.

In more recent years we’ve had star players grace the NHL such as Grant Fuhr, who Wayne Gretzky has called the greatest goaltender in NHL history. Fuhr was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2003. Do you remember Sidney Crosby’s ‘golden goal’ in the 2010 Vancouver Olympics? Edmonton born Jarome Iginla (who became the Calgary Flames captain in 2003) is the one who passed Crosby the puck, helping him make that beautiful Olympic win for Team Canada in overtime. It was arguably the best Canadian goal in recent history.

But when we fast forward to present day, with players such as PK Subban, on the Montreal Canadiens; we have to wonder how much things have really changed. A Norris Trophy winner, Subban is the best defender in the NHL right now, yet his own teammates publicly make negative comments about him and his “aggressive” style of play. His ice time is often mysteriously limited despite his glaring talents. Last year he was ranked #1 on Sports Illustrated NHL’s Most Hated Players list, citing his “flashy personality on and off the ice”. And fans often show up to games sporting afro wigs and Blackface.

One of the organizers of the Speaking Black Hockey event, Anthony Bansfield says the event is really about far more than Blacks in hockey. It is about resilience. “I was fascinated by the way the African Canadian community in Nova Scotia used the names of their hockey teams to convey their history and identity as a community that had successfully resisted slavery and started a new life in Canada. The name of one team, for example, was the Mossbacks, which relates to how Black people managed to make their way North at night, when they couldn't see the stars, to guide themselves by the way the moss grew on the trees,” says Anthony. Apparently, it tends to grow on the north side of trees.

Speaking Black Hockey will both entertain and educate in celebrating the contributions of African Canadians to the history of hockey. Anthony says he puts the “entertain” first and the “educate” second because it is important to have a good time! “The artists in the show are excellent, dynamic spoken word performers, actually some of the best in Canada, and Canadian spoken word artists are known as some of the best in the world. And, because many of us spoken word artists love to engage audiences by making use of music, theatre, visual art and other artistic disciplines, the show is enriched by a display of visual art and the use of video for multi-media performance.”

Now, after that... I may just become a hockey fan after all.

Editors Note: This article is by no means a comprehensive look back at the history of Blacks in Hockey. For deeper insight into the many talented Black players who left their mark on this sport, Black Ice by George and Darril Fosty is recommended.

By

By