I was sitting in a small room in my apartment, huddled at my desk, hovering over my laptop. I sat there in sweatpants and my favorite all-black hoodie. Alone.

I had done this too many times before. It never gets easier. I was about to watch another innocent and unarmed Black man die on camera in a confrontation with police. This time the man’s name was Eric Garner.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

I could have ignored the video. On principle, I could have decided not to watch it. I mean, doesn’t each click and view act as encouragement to share more videos of the same, only further desensitizing us all to scenes of Black suffering, brutality and death? So, did I really need to watch this?

No, I didn’t need to.

But I felt compelled by an obligation to bear witness to this fellow Black man’s final moments. I felt obligated to watch as a Black man. I felt obligated to watch as a lawyer. I felt obligated to watch as a Black lawyer with a human rights practice that focuses on police brutality against Black people.

So, alone, in the dark with my face lit with the glow of my laptop, I THOUGHT…“I’m about to watch a lynching”.

Soon after I pressed play, my pulse quickened. My breathing became short, strained. My hands began to shake over the keyboard. I could feel the thud of my heartbeat heave heavily in my ears. I began to vicariously feel the trauma of this man’s last moments before his lynching.

You’ll always find these three things in a lynching: (1)They are always public, (2) they feature mob violence and (3) they don’t just aim to kill the victim, but also serve to send a message to all other Black people like them: Comply or die. From the first moments of the video, I knew what this was going to be.

From where I sat, Eric Garner’s death looked like a lynching. He stood midday on a busy street sidewalk full of cars and occasional passers-by; the officers acted as a mob; and, Garner was soon going to be made into an example for daring to demand that the police respect his humanity.

“I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe” “I can’t breathe”

Then nothing.

Garner is left unconscious on the concrete. The video ends with several officers surrounding Garner, hovering over his limp lifeless body on the Staten Island sidewalk.

For how long, I don’t know, but I just sat there in the dark with Garner’s last moments looping my mind, his last words echoing through my consciousness: “I can’t breathe”

These words touched a chord in me that rings back through several centuries, starting with the enslavement of Black people. Garner channelled our centuries-old cry to be left alone to enjoy our human right to freedom.

It was a sentiment I too have felt as a Black man under the police’s constant eye of suspicion for living while Black. Garner’s feeling of being fed up with police interfering with his life was familiar to me. At different times, I too have felt the exhausting burden of my Black skin being marked as a threat, as inherently criminal. I too have felt that deep desire to just be left alone, the frustration of being accused of something I haven’t done, and feeling helpless as my accusers have already judged me guilty until proven innocent.

Like Garner, I happen to be a large, heavy-set Black man. I have felt the size and Blackness of my body be met with fear and seen as a sign of trouble. I know too much about just trying to be, while my body was being seen as a weapon and a danger needing to be monitored, controlled, contained, and if not compliant, slain. From my own experience I know that being big and Black makes it hard to breathe in Canada too.

To some that sounds like an exaggeration. Some might respond: “Toronto is not New York and Canada is not like America when it comes to these things.” True, but acknowledging the difference doesn’t dismiss the fact that anti-Blackness is borderless.

At the time I watched the video of Eric Garner’s death, by then America already had its #TrayvonMartin #MichaelBrown and #TamirRice. But Canada had its own hashtag memorials at that time too: Jermaine Carby, Ian Pryce, Frank Anthony Berry, Michael Eligon, Eric Osawe, Reyal Jardine-Douglas, Junior Alexander Mannon. I didn’t know then that names like Andrew Loku, Kwasi Skene-Peters, Bony Jean-Pierre, Alex Wetlaufer, Abdirahman Abdi and Pierre Coriolan would soon be added to the list of Black men lost to police violence in Canada.

So, watching Garner’s lynching, I felt the pain and horror of his last words in a visceral way, not as a foreign phenomenon. It was an experience regretfully resonant with Black life in Canada.

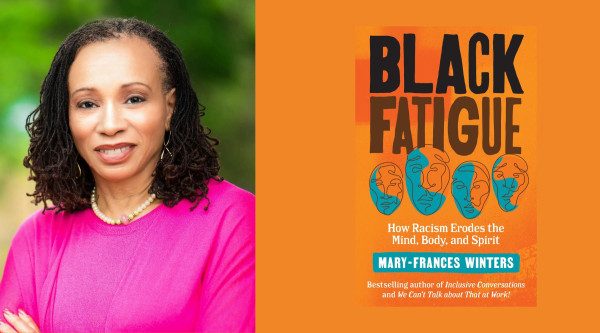

Too routinely, Black bodies are unjustly surveilled, intercepted and snuffed out by police in the Great White North. Not only is anti-Black racism real here, but it is forcefully denied when you try to point it out. As such, there exists a double burden of anti-Blackness in this country. This is what I call the suffocating experience of being Black in Canada.

I awoke later that morning with a clearer vision and more fervent commitment to using my work to help achieve racial justice for Black people in Canada. I decided then that I would do this work without worrying more about hurting white people’s feelings than I did Black peoples’ lives and well-being.

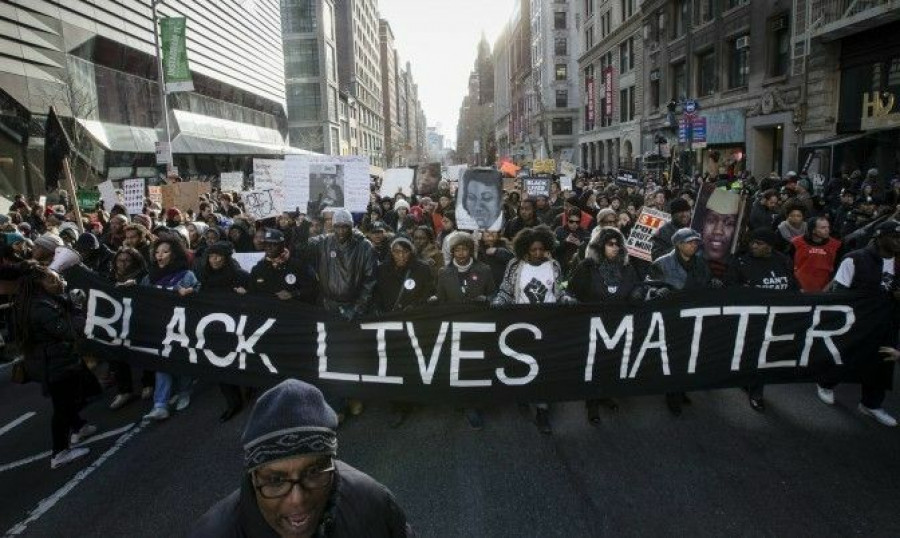

I didn’t know then that on the horizon was the emerging force of ardent Black advocacy that would become Black Lives Matter - Toronto.

Garner’s final words, “I can’t breathe” fostered within me a firmer and more focused commitment to supporting systemic change. I have been most unwaveringly committed to racial justice advocacy ever since.

Black people were not saved by a Black presidency. They still can’t breathe. Under Trump, African Americans, are more vulnerable than they’ve probably been in 50 years.

So, although the movement to fight for Black lives has grown exponentially since Garner’s fateful final words, there’s still much more work to be done. Considering this, I am still deeply committed to doing my part to support Black freedom. But I am always sobered by the reality that few have the opportunity to live out this fight for freedom as I do; by leveraging my professional position as a lawyer, to better the conditions of people like me, as a Black man.

So, in the end, what does this all mean? It means continuing to fight for more than just me.

I can’t breathe until we are all truly free.T

This personal essay was originally recorded for CBC's radio show Out in the Open.

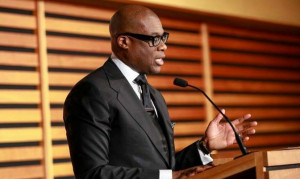

Anthony Morgan is a Toronto based lawyer who practices in the areas of civil, constitutional and criminal state accountability litigation. He has a special interest in anti-racist human rights advocacy, particularly in the area of anti-Black racism. He has appeared at various levels of court, including the Supreme Court of Canada, and has also represented the interests of African Canadians before United Nations human rights treaty bodies.

By Anthony Morgan

By Anthony Morgan