I mention this because the two of us were not face-to-face, but managed to roll our eyes in unison at the FBC’s statement of non-partisanship. Calling itself “non-partisan” was quite a stretch, given the ties its founding members have to the provincial and federal Liberal parties. I didn’t make my reservations about the FBC public, because, at the very least, I felt obligated to give the organization a chance to show its work before lodging criticisms.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

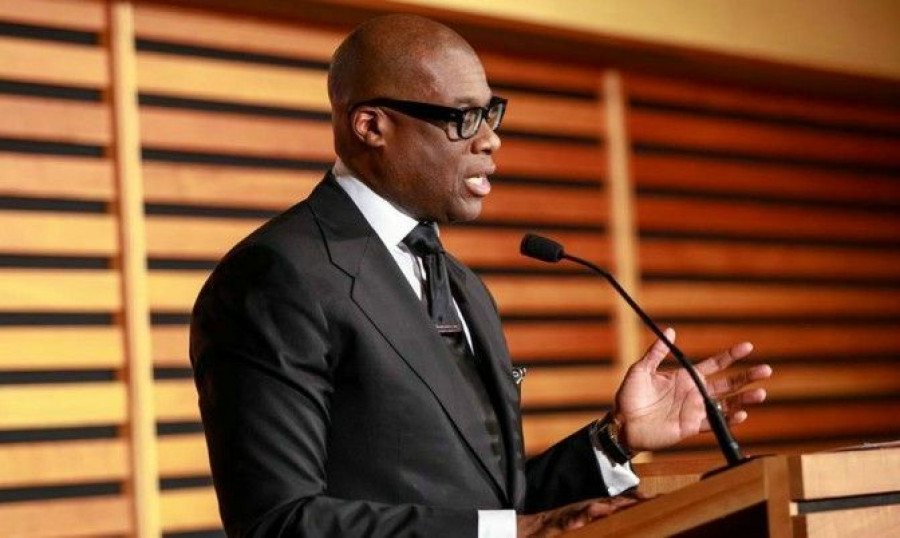

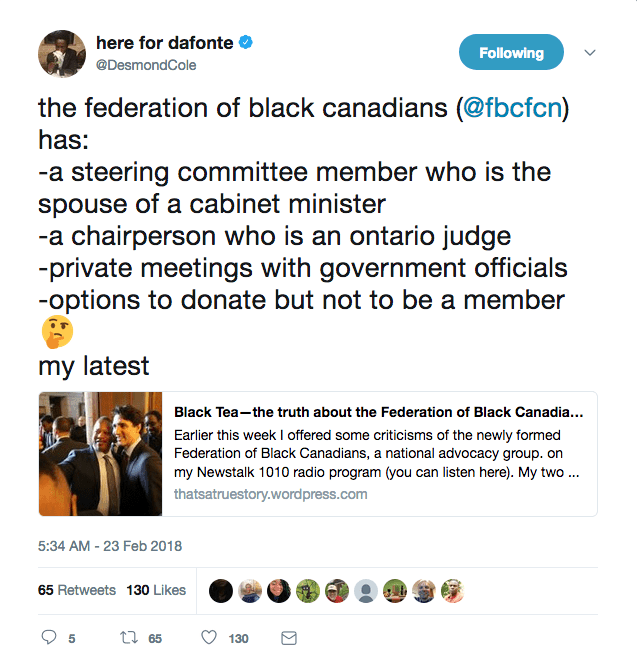

It’s been a few months since the FBC first crossed my radar, and two months since its National Summit in December. The FBC (and its Chair, Justice Donald McLeod) has been granted goodwill and ample headline space since the summit – at the very same time that grassroots organizers have mobilized to help prevent the deportation of Abdoul Abdi from Canada. On that matter, the FBC has remained publicly silent. When Desmond Cole criticized the Federation on his Newstalk 1010 radio program, it wasn’t unwarranted. Cole’s criticisms were for the FBC’s silence on the matter of Abdoul Abdi, for its ethical conflicts (how indeed can a provincial judge and the spouse of the Minister of Immigration engage in conflict-free advocacy?), and for a lack of transparency. People are able to donate to the organization, but there’s no option available to help lead the FBC or even join it in an official capacity.

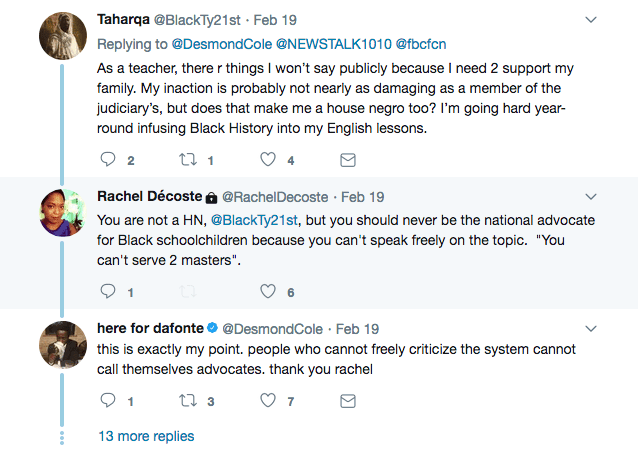

The backlash against Desmond voicing these critiques have mostly fallen along two narratives. One, that Desmond’s criticisms were valid, but he could have chosen a more appropriate venue to air out intra-community criticisms. Being someone who grew up watching similar conflicts play out within the community in the pages of Share magazine during the 1990s, I understand this point of view. These are conversations to be held within the community, and I don’t agree that Newstalk 1010’s audience has a place within that conversation.

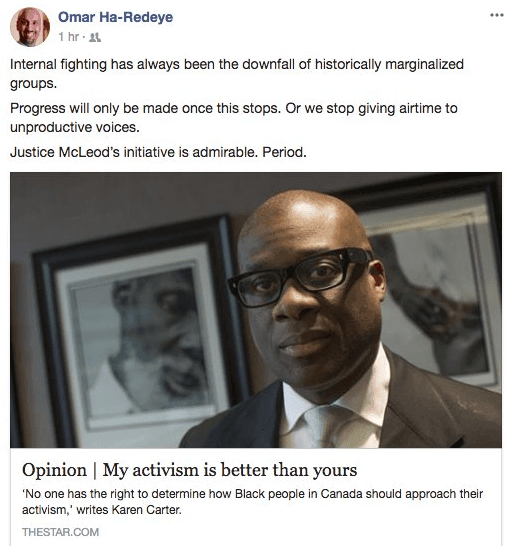

The second narrative is that Desmond has turned his powers of social activism against pillars of the Black community, seeking to tear down people and organizations whose means of activism differ from his own. The most egregious example of this was lodged in the Toronto Star – the publication Desmond left in order to have the freedom to speak uncomfortable truths – and accused Desmond of “attacking” Justice McLeod. This narrative is one that isn’t interested in nuance, or even in conversation. It’s an attempt to silence dissent and order wayward Black upstarts to fall back and get in line.

I’ve experienced this myself when members of the community turned on me for criticizing the Ford family. I’ve seen many people in the community do it when making cowardly and gutless statements like “Black Lives Matter doesn’t speak for me.” Karen Carter’s ministry may not be marching in the streets, and that’s anybody’s own right to determine what their activism looks like. But accusing Desmond of disparaging other people’s activism wasn’t only inaccurate, it was a flat-out lie.

As a matter of setting records straight, let’s understand what we’re talking about. Justice McLeod has a cachet within Ontario’s Black communities for his years spent as a criminal defense attorney who was tireless and vocal in calling out racial profiling by police. He has carried this work into his role as a provincial judge, speaking up about criminal justice reform and the lack of resources for those living with mental illnesses. Justice McLeod has earned his stripes. At the same time, Justice McLeod cannot have it both ways. If the purpose of the Federation of Black Canadians is – in the FBC’s own words – to “advocate on (our) behalf with governments, parliaments, international organizations, business, and faith-driven organizations” – then what does that advocacy look like?

Is the FBC’s advocacy available for me, as a Black Canadian, only when that advocacy doesn’t entangle its leadership in an embarrassing conflict of interest? Is it available to Abdoul Abdi, only insofar as Abdi doesn’t require Ebyan Farah (who left the FBC briefly after Desmond called out her placement) to persuade her husband (Ahmed Hussen, Canada’s Minister of Immigration), whose ministry is partially responsible for the deportation proceedings against him? Because if advocacy for Black Canadians requires that we cast our own people behind, the FBC can keep it.

Justice McLeod stood next to Justin Trudeau, and mentioned not a mumbling word about Abdoul Abdi. SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) showed up en masse to put Ahmed Hussen to the question on the matter of Abdi’s deportation. This isn’t a matter of whose activism is superior, it’s a matter of who is even engaging in activism to begin with.

On the matter of Desmond airing out community business with a network whose listenership is primarily white, there is merit to that argument. Some people on the FBC’s steering committee are acquaintances, if not friends of mine, and I get why they felt broadsided by this conversation. And while I don’t particularly care what white people think of our intra-community conversations, not everyone is positioned within their career, their finances, or even their families to share my feelings. I don’t believe we’ve had these conversations within our communities for decades because people are afraid massa is watching. It’s been done this way as a means of survival, and putting forth a united front.

But personally, I’m not a big believer in united anything. When we say “the Black community is not a monolith,” that’s not just a catchy phrase – it’s the truth. This also means we need the space to have loud, messy, and uncomfortable conversations, just as any other community does. Not so long ago, our communities were having very loud and messy conversations about the roles of the so-called “old guard,” the Jamaican Canadian Association, and the Black Business and Professionals Association, in the face of street-level activism in support of Black lives. I should know – I was making some of those very pointed critiques, and am currently the BBPA’s Communications Co-Chair. Many of those conversations took place within community publications, and both organizations have since taken on a more grassroots role, and pledged to be in closer communication with our activist networks.

It took these messy conversations to get our most well-established organizations on board. It’s going to take more of these conversations to get the Federation of Black Canadians on board.

The fact that Desmond Cole is the one currently leading that conversation says nothing about Desmond. But it says plenty about the FBC, which not only had countless examples to help it strike the right note within our activist communities, but a heaping benefit of the doubt from the people it claims to represent. On that count, the Federation has failed. And I don’t believe it can move forward in its current form. Not with the ethical questions its leadership has failed to answer.

Regardless of the way they spoke up, Desmond Cole and other activists who’ve spoken up are correct. It shouldn’t have taken a call-out on public radio for this conversation to happen. It is a great idea in principle, but if the FBC cannot advocate for one of us, I don’t see how it’s possible for the FBC to advocate for all of us.

Correction – March 5, 2018: This article previously misstated that Black Lives Matter confronted Ahmed Hussen in person. The group which did so was the Toronto chapter of SURJ. Andray Domise and ByBlacks.com apologize for the error.