The museum was a sombre, weathered structure which kept most of its original architecture and drew visitors down a winding path through the city’s shameful history as one of the South’s most important slave-trading hubs. When our morning visit was concluded, I wanted to talk more about what we’d just witnessed, but a longer discussion about slavery wasn’t on the itinerary.

We lunched a few blocks away at the City Market and were free to browse the local vendors’ wares. Cookbooks, paintings, baskets made of sweetgrass, and other curios. But there were a few stalls where keychains, bracelets, and postcards bearing the Confederate flag covered the tables. At one of them, I found a cloth figurine topped with a straw hat. The figurine, meant to represent a negro field worker, had a face of jet-black cloth. Its eyes were made of white acrylic, and bright red felt gwas lued beneath them for its lips.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

The woman behind the stall, a white lady with dull blonde hair, smiled at me. “That’s five dollars," she said, absently pulling a gift bag from underneath the table. “See anything else you like?”

I remembered my face growing hot, and I dropped the figurine and walked away. I kept my distance from my classmates for the rest of the day, and though a few of them asked, I couldn’t explain at the time what was bothering me, and why I was angry. Our class had witnessed Black enslavement memorialized in suffering one morning and memorialized as amusements and baubles the same afternoon. Later that day we continued our conference with no mention of either. Black pain had become something to stop, gawk at, and move on.

Those feelings came to the surface recently as I watched Black Mirror, Netflix’s popular dystopian sci-fi series. The fourth season, steeped in stories about memory, experience, and identity, culminated in a final episode dubbed “Black Museum.” The episode was an anthology, in which an older white huckster walks a young Black woman through his roadside museum, a near-forgotten tourist trap, explaining the horrifying “tech crimes” behind each exhibit. A glowing hair net, which transmits sensations from one person’s brain to another, is used by a pain-addicted doctor to inflict torture on others. A teddy bear containing the consciousness of a woman whose comatose body was removed from life support. His final exhibit, hidden behind a curtain, was a mock-up of a jail cell containing a conscious digital re-creation of a man wrongly sentenced to die.

Once, visitors would flock to the museum and pay a fee to pull the executioner’s lever, watching the man’s avatar scream helplessly as electricity coursed through its body. When the show was over, the machine would pop out a token for the visitor – a digital keychain with another conscious re-creation of the convict, his face frozen in rictus for eternity. “Stuck forever in that one perfect moment of agony,” says the museum-keeper. “Always on. Always suffering.”

While Black Mirror’s cast is typically diverse, racism exists more as a subtext for the show than a germane topic. Not so in the final episode; by the end, a plot twist revealed the convict was most likely innocent of the crime, and his daughter turned out to be the lonely tourist who’d visited the museum to exact her family’s revenge on its owner. Even in the future, Black people are memorialized in their suffering, even existing as a sideshow and a curiosity for wayward tourists.

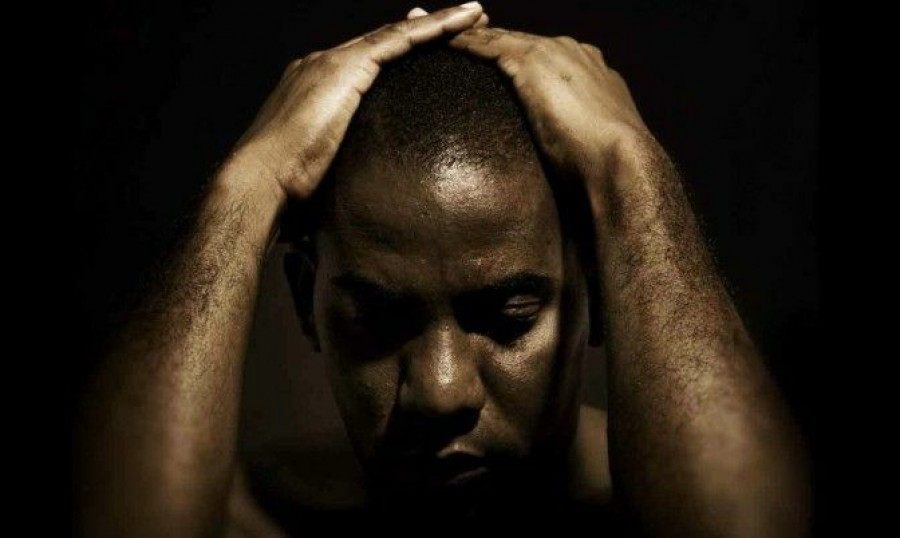

Bizarre, perhaps. But consider how the conversation on police violence against the Black body changed once cell phone footage, shared across social media platforms, brought incontrovertible proof to millions of smartphone screens. Our suffering and pain, whether from bullets blasted into the Black body or metal poles grasped by white supremacists, was required to make people believe that our fear of people in uniform or of young white men shouting slogans and wielding torches was justified. “The iPhone may well have done more to expose racism in modern-day America,” writes Foreign Policy’s Max Boot, “than the NAACP.” Despite museums recounting the history of the slave trade, and endless texts documenting brutality at the hands of police and of white mobs, from the Reconstruction era to the present day, it takes live footage of our final moments before anyone believes us.

This is why I hope that going forward, society can find better ways to discuss and share information about Black lives, outside of our relationship to suffering. Some members of the Federation of Black Canadians, for example, are lobbying Parliament to create an African-Canadian museum in Toronto. In St. Catharines, Ontario, community members are still raising funds to restore the historic British Methodist Episcopal Church, which once counted Harriet Tubman among its congregants. After an apology for its obscenely racist “Into the Heart of Africa” exhibit in 1989, the Royal Ontario Museum is working with the Coalition for the Truth about Africans (as well as members of the wider Black community) to address the history of Africa and the diaspora.

By now, we should be able to take for granted that yes, systemic racism is still a problem, yes, Black people are often profiled by police and by private citizens, and yes, Black people often lose their lives as a result. By all means, share the word, call local representatives, and demand accountability. But as long as we’re in the business of sharing, then consider spreading awareness of local organizations that support our communities, and perhaps donating to them as well. Just consider that the next time you have the impulse to share a shocking video of racialized violence, there’s a human being on the other end whose pain is being captured for eternity.

You shouldn’t have to see it to believe it.