Why did the Black boy drown? Because he couldn’t swim.

And he couldn’t swim because learning to swim is one of those intersections where race, space and class collide. Black people in the United States drown at five times the rate of white people. And most of those deaths occur in public swimming pools.

Jeremiah Perry drowned on a school trip last summer. The group of 33 teenagers and their teachers were enjoying a classic Canadian experience – canoeing in the wilderness. The group stood out in Algonquin Park because most of the kids were Black. And finding Black people in the woods is rare.

The swimming ability of the group quickly became a key issue in the preliminary investigation into Perry’s death. It turned out that half of the kids could not swim.

Jeremiah Perry in an undated photo.

Swimming lessons

Swimming lessons are a rite of passage for most Canadian children. But race complicates the splashes, shrieks and laughter in swimming pools.

In Canada, immigrants are less likely to learn to swim or to swim as recreation. Most Canadian newcomers hail from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. Jeremiah Perry was a recent immigrant from Guyana.

In my old multicultural Toronto neighbourhood of Parkdale, some 90 per cent of the kids learning to swim were white. In my new neighbourhood of Regent Park, which started with Toronto’s oldest social housing project, more than half the population are people of colour and recent immigrants. They don’t appear to like swimming because the free municipal pool still overflows with white people. Yet the park around the pool is filled with brown and Black people enjoying the outdoors and frolicking in the sprinkler fountains. For them, taking the step from outside to inside the swimming pool seems to be as hard as trying to swim across the Atlantic Ocean.

‘No trees in the water’

Warm seas and golden sandy beaches and are standard icons in tourism images of the Caribbean. So too are hotels with deep blue swimming pools. Surrounded by so much water, one would expect Caribbean people to be expert swimmers. They are not.

Most swimming pools in Jamaica are owned by hotels catering to tourists/Shutterstock

The majority of Caribbean swimming pools are owned by hotels and cater to tourists. Race colours the pools. Most of the people in the pools are white visitors, while those cleaning or serving cocktails at the pool-side bar are Black locals.

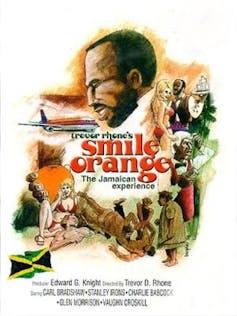

‘Smile Orange’ (1976) takes a critical look at tourism in Jamaica. Smile Orange/Knuts Production

Seen through this lens, as shown in the classic movie, Smile Orange, hotel swimming pools are the continuation of the old colonial project — white people at play, cooling off in the water, in a country club style setting. Black people at work, sweating in the hot sun. Not allowed in the pools.

Most people in the Caribbean don’t have access to swimming pools. If they want to learn to swim, they must do so in a natural body of water such as the sea or a river.

As a child in Jamaica, my grandmother forbade us to go to the sea. “There are no trees in the water,” she warned us. Every year some child drowned, going out of their depth, silently sinking to a salty, watery grave.

Drowning in racism

I learned to swim in England, where weekly swimming classes were a standard part of the school curriculum. A report from the Amateur Swimming Association showed that there is a pent up demand for swimming from Black people in England. Most don’t go to the pool because they don’t see other Black people swimming. The same report indicated South Asians are the least likely to venture into the water.

Swimming and African Americans are not a classic pairing either. Imagine a pool party. The Black people mingle around the pool, while the white people are in the pool.

June 1964. Black children integrate the swimming pool of the Monson Motel in St. Augustine, Fla. To force them out, the manager of the motel pours acid into the water.

Horace Cort

African Americans’ antipathy towards swimming is rooted in segregation and racism. It was not so long ago that public beaches and pools in the United States displayed “Whites Only” signs. Blacks who entered these beaches were chased off or got a good beating. Pools were drained if a Black person got in. One Black person contaminated the whole thing.

Segregation continues today, but it is more subtle. Most white children learn to swim in pools that are in private recreational clubs in the suburbs. Black children often contend with poorly maintained and over-crowded public pools in the urban centres — if pools exist at all.

If parents can’t swim, it is less likely that their children will learn to swim. Parents fear of drowning means they are unlikely to sign up their kids for swimming lessons, even when these are available.

Drowning while Black

I like to do laps in the swimming pool for an hour or so. Front-crawl up the length of the pool and breast-stroke on the return. Dreadlocks streaming down my back. Keeping time with the clock. Every so often I will get the look. Whether from a Black or white person, it expresses surprise that I am at ease in the water. Sometimes, it starts a conversation.

How many times have I heard that Black people can’t swim because our bones are too dense? Or we can’t float as our big bottoms drag us down under the water?

Led by the activist Edward T. Coll, a group of parents and children from inner-city Hartford lead a protest march in the 1970s in front of seaside mansions in Old Saybrook, Conn.

Copyright and courtesy Bob Adelman

These comments attempt to use genetics to explain the low rate of swimming among Blacks. Scientific racism is nothing new when it comes to the Black community. Its original purpose was to justify slavery.

The echoes of past stereotypes continue to shape Black lives. In the case of swimming, scientific racism now claims that Black people are less likely to swim as, our muscles don’t twitch at the right speed.

These explanations avoid looking at how swimming and systemic racism intersect. They do so on so many levels in my local pool. The pool’s general advertising reaches middle-class white people from outside the neighbourhood, they drive to it attracted by its award-winning architecture. The pool has done little outreach targeting the Black community, including advertising swimming lessons for its children.

Swimming to the future

Swimming is part of the cultural capital of a middle-class lifestyle. The poorer you are the less likely you are to learn to swim or visit a pool. The spectre of colonialism lurks. The high drowning rates among Black people is merely another symptom of the after-life of slavery.

Olympic swimmers are the apex of achievement in sport. For a long time, Black people were absent from the elite swimming teams. The first Black person to win an Olympic medal in swimming was Enith Brigitha in 1976 Montreal Olympics. She was from Curacao in the Caribbean and swam on the Dutch team. In 1988, Anthony Nesty from Suriname became the first Black man to win an Olympic gold in swimming.

Each decade the number of Black swimmers at the Olympics Games increases. The latest was Simone Manuel, the first Black woman to win a gold for the U.S. in swimming at the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Black swimmers at the Olympics gives hope that swimming is shifting from a white sport to a more diverse one. As attitudes shift, more Black children should learn to swim and the drowning rate should fall.

Jacqueline L. Scott, PhD Student, University of Toronto

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

By Jacqueline L. Scott

By Jacqueline L. Scott