Dr. Akwasi Owusu-Bempah and Storm Jeffers spoke to 224 participants--a mixture of youth, their families and other stakeholders involved in the Criminal Justice System--and what they heard was disgusting, yet familiar.

The participants shared their stories with the research team, including stories of prejudice and targeted discrimination, “I would be with three people and I’m the only Black guy; the white guy speeding and me, the Black guy in the back seat. They would single me out and ask me questions. If there was a white girl in the car, they would ask her if she’s okay.” There are fear-filled stories of police interactions, and a feeling of helplessness to do anything about it. “An officer even went as far as saying one time ‘I’m going to do everything in my power now to throw you in jail’”. And there are also stories of incredible loss, “CFS family services made things very difficult for me to manage at home… All I needed was support and they took my kids away.”

I’ve written before about the Toronto Police apologizing for racial discrimination, but not making any real change, and I’ve also written about the persistence of anti-Black racism in Ontario, but Owusu-Bempah and Jeffers capture a truly national snapshot, from Toronto and Ottawa, Halifax and Montreal, to Winnipeg and Calgary of theBlack experience when it comes to policing.

While Black Canadian communities are incredibly diverse, our stories are much the same: from over-policing at school (see school-to-prison pipeline) to the lack of mental health support, to over-policing of the Black home and the Black parent (see child welfare system), and over-policing of particular communities (see carding) - the system is stalking us, waiting for us to get stuck in a web that we were born into.

But we knew that already.

The question remains, how do we resolve it? The study has many suggestions, and guess what? Not one of them includes giving more money to the police. Quite the opposite. And this may be the best set of recommendations I have seen regarding the issue of supporting Black youth to manage white supremacy. Here are the top 5 I’ve pulled from the report:

- “Provide post-secondary education funding for Black youth.” (p.34)

- “Redirect funding from police presence in school settings toward the provision of adequate mental health and conflict resolution professionals.” (p.35)

- “Establish an independent complaint-management body that youth and parents can access that ensures remedies and accountability for anti-Black racism in schools” (p.36)

- “Establish a nation-wide database that tracks complaints and penalties for police misconduct. Prohibit the hiring of officers who have been fired for this reason in other police forces or cities.” (p.38)

- “Assess the explicit racial biases of people seeking work as parole and probation officers. Set a zero-tolerance limit that must not be transgressed.” (p.42)

- The same for teachers (p.35)

- The same for police (p.38)

- The same for those seeking work in youth detention and custody centres (p.41)

Owusu-Bempah and Jeffers also spend a lot of time explaining the prolonged impact of first contact. They explain that in many cases, “first contact with the system, in the form of policing, came very early for many youths, often in schools and within their neighbourhoods. At times, first contacts were absent of any criminality on the part of these young people.” (p.8). It is these first contacts that create the relationships that notoriously exist between Black communities and police, marked by the mutual perception of inhumanity where police see Black people as animalistic and overly violent and Black communities see police as ruthless and evil.

But it isn’t just the police, as indicated by their recommendations, other government actors are also actively participating in the systemic poor treatment that disadvantages Black youth. The study participants “spoke of abusive, violent, and potentially criminal treatment by custodial facility actors” adding that “poverty, language barriers and mental health struggles [actually] worsened treatment” (p.45). They share two examples from Montreal that made my blood boil:

- “A Black mother shared that the school called the police on her 12-year-old son because he angrily lifted a desk.” (p.15)

- “Youth talked about being made to feel like objects or animals, and one youth reported being forced to eat snow during a police interaction” (p.25)

And the final nuance, that only some of us are aware of, is how exhausting it is to actively fight disproportionate outcomes and advocate for systematically oppressed groups. The authors shared some insights from a service provider in Toronto that they spoke to who said, “There was a Black officer at the… Centre who was targeted, tires slashed, food poisoned and forced to leave by white officers because he noticed a Black youth had mental illness and tried to advocate officers...” (p.29)

But again, how many stories do we need in order to be convinced that Black lives, and Black potential matters?

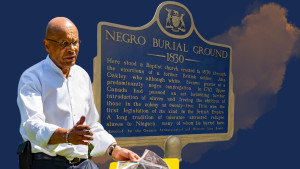

This weekend I was frazzled by the side-by-side image of two stories unfolding simultaneously. A Black man shot more than 60 times by police in Akron, Ohio, beside the image of a heavily armed white man who was quietly, peacefully arrested by police after killing 6 people and injuring more than 30 in a shooting attack at a Fourth of July parade near Chicago, Illinois. In broad daylight.

Enough storytelling. We need justice.

By

By