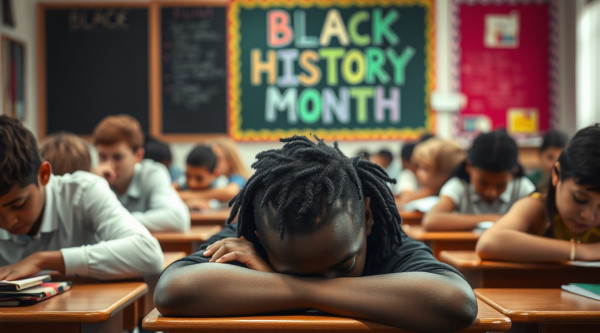

It marks renewed learning about our collective African Canadian history, unlearning the erasure of Black life in white settler mythologies, and uncovering a fuller picture of the roots of anti-Black racism and Black resistance in Canada.

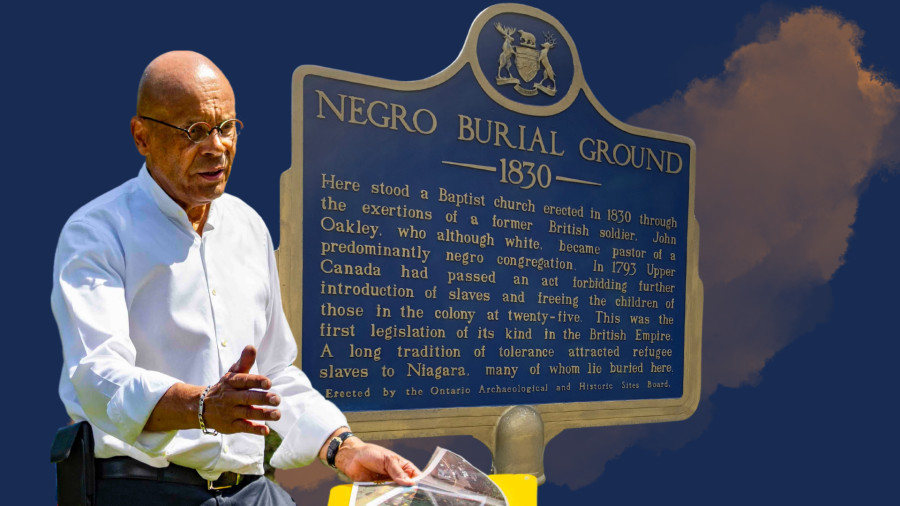

James M. Russell is a Toronto-based Black filmmaker who took up the herculean task of uncovering the unmarked graves, headstones and eventually names of early Black settlers in the Niagara-on-the-Lake cemetery. “Travelling back and forth to visit [the region] since 1985, 37 years, and it always bothered me that the Negro Burial Ground was an empty grass field, two headstones and other than that just grass.”

Niagara flourished for years as a site where many free Black families, including Black Loyalists who served in the British military, settled in the 1830s. In comparison, others were forcibly brought into Canada to this region as enslaved persons in the late 1700s after the American Revolution.

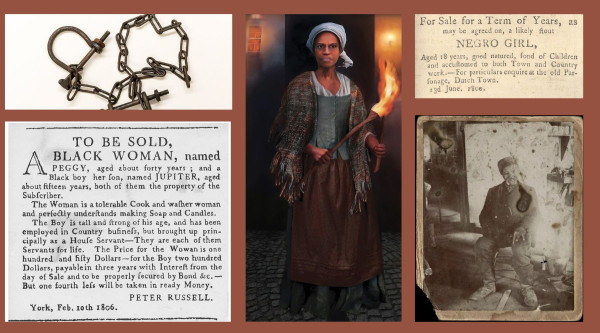

The abolition of slavery certainly did not happen overnight. The Act to Limit Slavery of 1793 was the first legislation of its kind in the British Empire. However, while it prohibited the enslavement of Black freedom runners newly entering Canada, it sanctioned the continued enslavement of Black folks in Canada—relegating Black children to unfreedom until their 25th birthday. These counter-narratives reveal the true history of Canada’s 200-year-long legal practice of enslaving people of African descent and Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Last November, Russell applied to the Town of Niagara to use ground-penetrating radar on the Negro Burial Ground on Mississauga Street. Many Black community members lived in what was once known as the Coloured Village, located near the Baptist Church. So far, 28 graves and 19 headstones have been found at the site.

When asked what lessons we must draw from Indigenous communities, led by Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in the 2021 discovery of the 215 Indigenous babies and children’s graves at the former Kamloops Residential School in B.C., Russell says: “The lesson for us Black folks is that no one will uncover our history if we don’t do it ourselves.”

Natasha Henry-Dixon, Assistant Professor of African Canadian History at York University and President of the Ontario Black History Society, reminds us of the importance of naming and taking an interdisciplinary approach to uncovering the stories of early Black freedom seekers. The Ontario Heritage Trust commissioned her to conduct background research and update existing plaques of the Niagara Baptist Church.

The old plaques at the site anchored Black lives to the efforts of white people, and Black people were largely absent from these narratives. In contrast, the research led by Black historians like Henry-Dixon recognizes Black people as subjects with a long history and presence in the predominantly white Niagara region.

A critical aspect of Black Canadian history involves uncovering the freedom seekers buried in the Negro Burial Ground of the Niagara Baptist Church, established in 1829 by a white British soldier, John Oakley. The church was recognized as a space for the Black congregation in the 1850s and led by Black Baptist minister Francis Lacy, who kept records ensuring that children and adults who were part of the predominantly Black Baptist community formed part of our collective historical record.

Henry-Dixon documents at least 15 burials in the churchyard, including Black freedom seekers Herbert Holmes and Jacob Green. They were killed in 1837 protesting for the release of Solomon Moseby, a Black freedom seeker set to be extradited across the Niagara River back into slavery in the U.S.

“These are entry points into further research and reading, and one of the things I was so elated with in regards to the heritage plaque, is to include the background reports so that people have ready access, and can dig deeper for themselves,” says Henry-Dixon.

The archival research and ground-penetrating radar technology involved in Russell’s project “speaks to the interdisciplinary approach that has always been taken to document and uncover Black history,” she says.

For Russell, racial justice begins with honouring the humanity and dignity of the living and ancestral Black communities. “Those folks built Canada; they had an important role in building Canada back in the 1700s and 1600s, their unpaid labour paved the way for the wealth of Canada, and it’s important that these stories are told.”

Black communities have long been organizing and demanding symbolic recognition and material reparations to redress group-based harms and stolen labour that served as the bedrock of pre-Confederation Canada and modern-day capitalism.

If these graves remain unmarked and the stories of Black ancestors remain relegated to acts of collective forgetting, we can’t bring the lessons of the past to bear upon us. For emancipation and Black liberation to be fully realized, Canada needs to reckon with its historical roots—forged by Black agency, self-determination, and resistance.

By

By