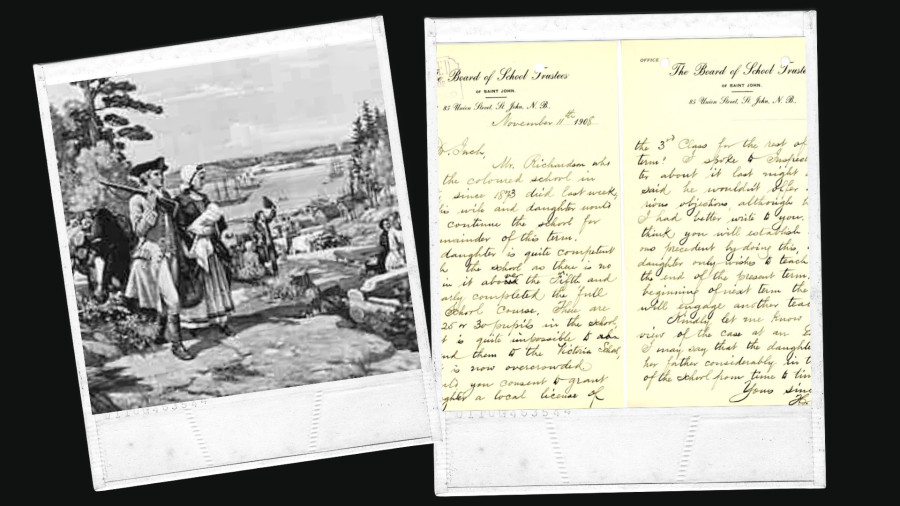

In 1767, in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, slavery was still pretty much legal. But fourteen years later, in 1781, Black people arrived as ‘freedmen and women.’ They were Black Loyalists who were freed after fighting alongside the British during the American War of Independence.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, the 433 Black ‘freedmen and women’ who chose to call Saint John, New Brunswick home were not welcomed and were deliberately given land that could not grow agriculture. Because of this, some of these Black people returned to work as indentured servants to survive.

Upon hearing about this, a gentleman named Thomas Peters planned an exodus to Sierra Leone, and in 1792, 1,196 Black people from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia left and resettled in Sierra Leone. From 1812-1816 another 400-500 Black people arrived in New Brunswick after the War of 1812. In 1820, the first segregated African school, Otnabog School, was founded, and in 1848 a Negro Day School was also created by the government.

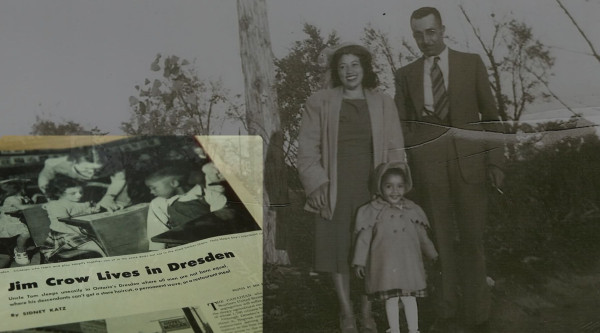

Despite these means of keeping Black people separated from white people and treated differently, the University of New Brunswick still had Black students who graduated with Honours and many innovators and notable people. In 1833 slavery was abolished in New Brunswick, although no enslaved people were left in the Maritimes. By the turn of the century, the segregated schools also closed, and the ancestors of those children still live in Saint John today.

According to documents from the New Brunswick Association for the Advancement of Coloured People from 1969, Black people in Saint John were experiencing a “cultural genocide” as they were not selected for jobs and were forced into unskilled work. In addition, women were forced out of the home and into work. Although 18,960 employees were hired by 55 firms in St John, in 1969, only 88 were Black and 24 of those 55 indicated they “hire Black people sometimes.” This racism has had a profound effect on the Black community of Saint John and repercussions are still being felt today.

Matthew Martin, Executive Director of Black Lives Matter New Brunswick (BLMNB), comes from generations of Black people who called New Brunswick (and before that, Nova Scotia) home. Before working with BLMNB, Matthew worked at a jewellery store and was passionate about the jewellery industry.

After the murder of George Floyd, Matthew organized a rally with some other community members. He saw a need for an organization whose “mission and focus are to support Black community members and their needs such as employment, food security and activism. After some discussion, it was clear that something needed to be done because if we don’t do something, who will? And this is the birth of BLMNB.”

The work of BLMNB so far includes research on Systemic Black Racism in New Brunswick in partnership with New Brunswick Community College. Matthew shares, “this research has allowed BLMNB to have a great picture of the data (or lack of) in New Brunswick. 2022 and 2023 have seen some great growth within our programming. We have an amazing youth program that focuses on the needs of youth, eliminating any barriers that they may face to ensure they succeed in all of their goals.” BLMNB has also started to curate a visual art display in partnership with New Brunswick College of Craft and Design, promoting Black artists and their art within New Brunswick. They also offer educational presentations in various industries and areas such as “employment, recreation, and educational institutions.”

Recently BLMNB has worked on a Youth Outreach Program in partnership with the John Howard Society to address the needs of Black youth within New Brunswick. The program is designed to eliminate systemic barriers and ensure that Black youth have every possible opportunity to be the best version of themselves. The project has allowed Matthew’s team to liaise with schools helping to quell discrimination and bullying and to uplift Black youth in various schools across New Brunswick. Matthew tells us they also have exciting projects for this year and continue to have meaningful discussions on “racism, systemic racism and anti-Black racism.”

Matthew says Saint John is modestly diverse, but the diversity isn’t reflected in leadership or executive positions, and it’s an issue that needs to be addressed.

For more information about the history of Black Loyalists in New Brunswick, visit https://www.discoversaintjohn.com/black-loyalists-new-brunswick

This story is part of our "Black History Month" series, where we celebrate the remarkable journeys and accomplishments of Black Canadians.

By

By