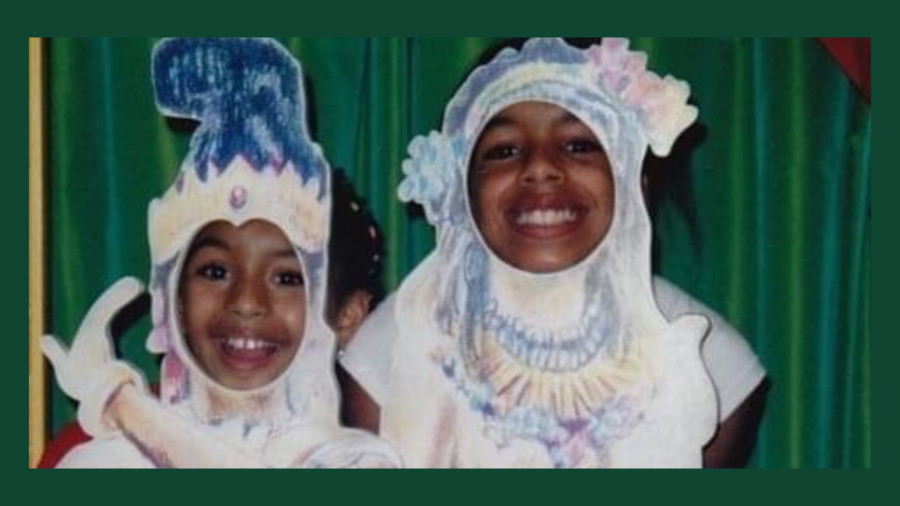

I had to be the smartest to hide that we were on welfare. I had to be the best behaved because my godmother taught at my school, but I also had to laugh at the Black jokes, grow a thicker skin, code-switch and bear different responsibilities. It was not until recent reports, getting an education and leaving New Brunswick, have I been made aware of adultification bias.

Adultification is a form of prejudice, primarily impacting Black girls and BIPOC children who are denied the type of protection society naturally grants children. Simply, Black girls are not perceived as innocent, not allowed to have as much fun, and forced to grow up faster. Additionally, they have more responsibilities and expectations burdening them simply because they are a different pigment.

The CBC recently reported on the work of Stella Igweamaka and Nana Appah, who co-researched adultification bias as the winners of the 2022 Canadian Research Got Talent competition, organized by the Canadian Research Insights Council.

Their research found that respondents viewed Black girls from zero to nine as more “adult-like than their white counterparts.” Twelve percent of respondents also felt “Black girls aged five to eight took on more adult responsibilities compared to eight percent of white girls. In addition, Black girls aged zero to four were nearly twice as likely to be seen as independent compared to their white peers.”

When I look back on my formative years, I wonder how much of the responsibility put on me was life circumstances or the people around me thinking I was somehow more capable, should already know things that meant I had less innocence and didn’t deserve as much grace and slack as my white peers.

I took so much pride in always being the student allowed to roam the halls and return borrowed items from other classes or the libraries, bringing the TV on wheels back to the tech lab, and conveying messages from teachers to the office when email wasn’t fast enough.

I saw those moments as trust, but now I see them as isolating. That trust caused me to earn my label as a teacher’s pet. Those responsibilities meant I spent less time in class with my peers learning because I was regularly assigned these specific tasks.

While I was always proud I had earned this trust from the adult teachers I saw as peers, sometimes more so than the kids my age, because I felt I was excelling in my class, I realize now that this Adultification also set me on an unfortunate path with my Blackness.

While recently watching a screening of the documentary Working While Black by the TAIBU Community Health Centre in Toronto, I became aware that all Black people suffer from the symptom of their Blackness at work. Meaning because of their skin and without reason, their melanin affects how they are perceived in the workplace. This workplace racism can come in the form of a lack of opportunity, microaggressions, overt racism, and lack of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion training.

A less obvious result of being a Black person in the workforce is the subconscious belief that we must all give 150% to be perceived the same as a white colleague with mediocre performance. As a result, Black employees work harder for fear of different treatment, job loss, ridicule and maintaining homeostasis. We become ‘yes people’ in the workforce to not ruffle feathers, to appease our white colleagues and bosses and often do not advocate for ourselves for fear of being perceived as rude, aggressive, or violent.

It is not lost on me that the groundwork for this behaviour starts with the adultification bias. For example, would I see being handed more tasks at work as a sign that my boss sees me as capable if teachers hadn’t done the same to me? Is this extra labour being given to me because I have been forced into being docile for fear my existence will upset the apple cart?

Convincing Black people they must work harder to exist in smaller spaces starts when we are children. It begins when we take innocence away from little girls who deserve to be running on playgrounds and instead hand them extra responsibilities. The adultification bias, unfortunately, is another chapter in a long book contributing to systemic racism, but the research and work done by Stella Igweamaka and Nana Appah will hopefully shed light and education on this unfortunate reality.

By

By