At one point, Downing asked, “How many of you are proud to be Black?” In the audience, which represented the diaspora of our community, many people raised their hands.

After a few seconds’ hesitation, so did I.

What was it that gave me pause? It all comes down to how I look.

Photo credit: Good Co Productions. A live discussion between Hanif Abdurraqib and Antonio Michael Downing

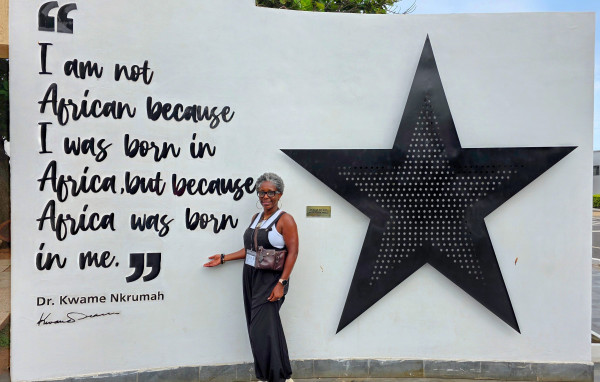

I was born in London, England, and my parents were from Guyana (British Guiana). The first of my mother’s ancestors to live there was my great-great-grandfather Yang-A-Pat, a Hakka Chinese who arrived in 1861. He laboured as an indentured sugar cane reaper, part of a post-emancipation wave of immigration in the Caribbean. I have a family tree of my Asian ancestry, framed and mounted on my office wall, which goes from Yang-A-Pat to my generation.

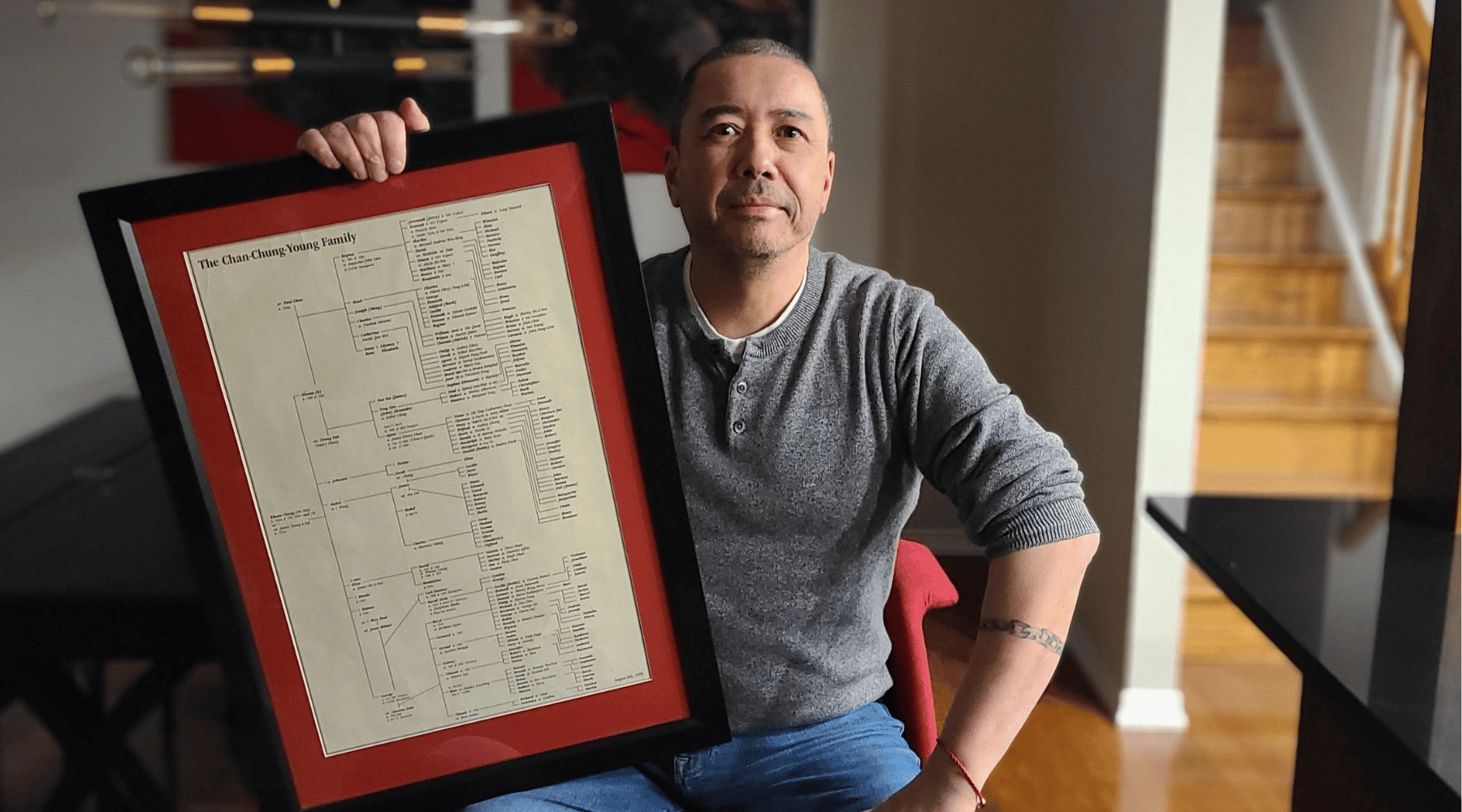

Nigel Gordijk with his Chinese-Guyanese family tree.

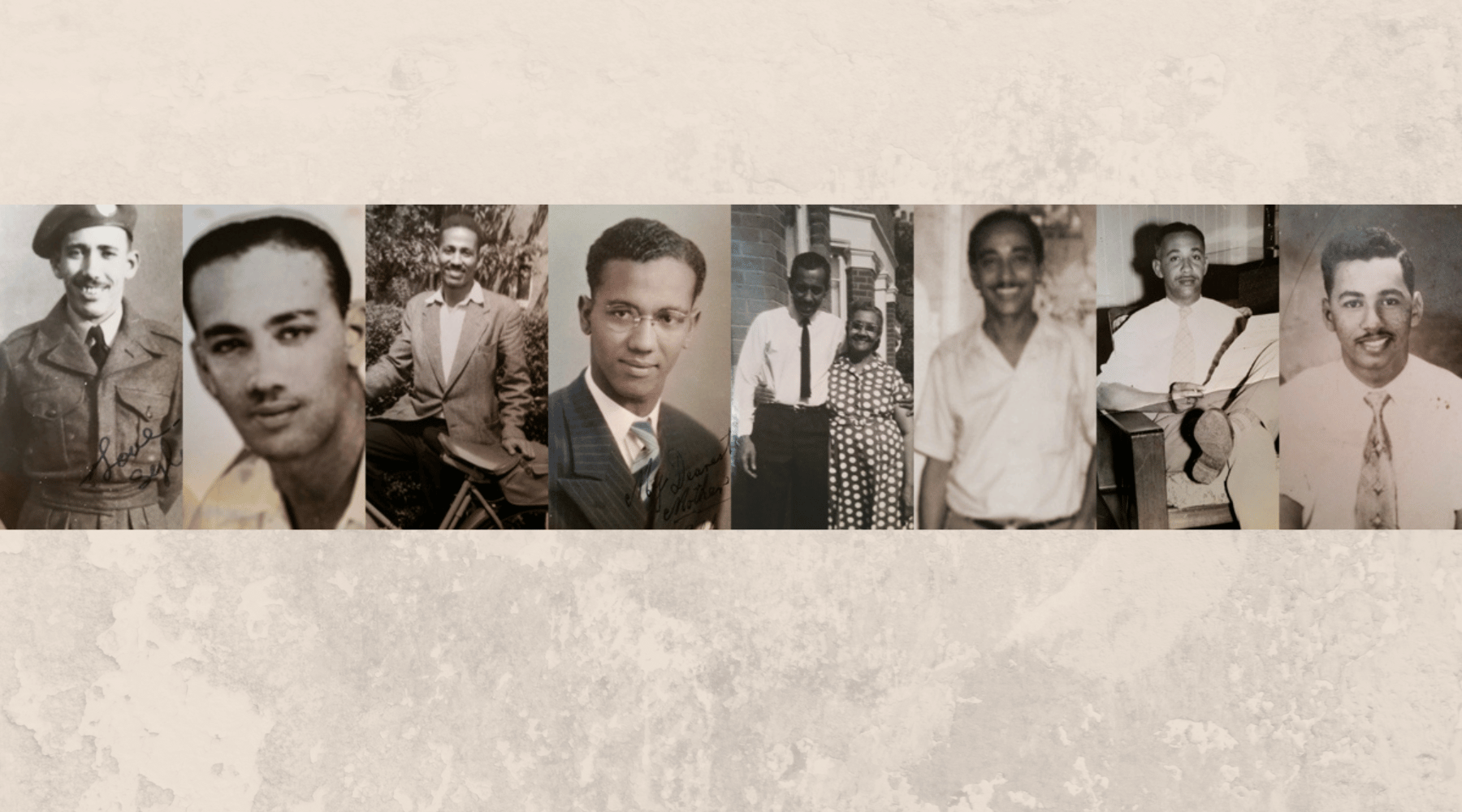

My father’s parents were born in Suriname (Dutch Guiana), but all I knew about them was their names and dates of birth and death. Also, having seen their photos, I knew they were Black.

My father, Sylvion Gordijk, at left, with his seven brothers.

I’ve been able to embrace my Chinese heritage my whole life, but I’ve only known the details about my Black ancestors for a few years. The mystery of my African ancestry led to an unbalanced sense of cultural identity.

That began to change when I connected with Kitchener-Waterloo researcher Peggy Plet, who is also from Suriname. I asked Peggy to help me trace my father’s ancestors, and in February 2021, she introduced me to my great-great-grandmother, Betje, the last person in my family to be enslaved.

Betje, whose name is a Dutch short form of Elizabeth, was bought and sold several times. Illustrating the complex history of slavery, the last person to buy her, Anna Pieternella Groenhout, was a Black woman who had been enslaved herself until 1839. Two years later, she bought my ancestor to be her housemaid.

Betje earned money on the side, probably by doing odd jobs and selling goods at markets. From 1853, she began the process of buying her four children out of captivity – including my great-grandfather, Frederik, in 1861 – through a practice called manumission.

Enslaved people had only a one-word name, and Betje’s liberated children were the first to use the family name Gordijk, after it was assigned to them by a Dutch clerk. By 1862, Betje had earned enough to free herself, too, and she took on the same family name as her children. I am only the third generation to be born with the last name Gordijk.

Betje died in 1898 at the age of 76, having lived the last 36 years of her life as a free person. That was long enough for her to know and hold my grandfather, James.

The sudden arrival of my Black ancestors was exhilarating, but it also came as a shock. This was the past that I never knew existed because my father hadn’t spoken about it, and it had never occurred to me to broach the topic. I don’t recall anyone on my father’s side of the family describing themselves as Black (or anything else), even though they clearly were. No one had ever mentioned slavery, let alone its connection to us.

Why were we all silent?

Peggy told me, “I think that goes for a lot of families, not just yours. Shame is a lot of what’s contributing to these feelings.”

I used to wish that I could share this new-found knowledge with my father, who died in 2003. Now I wonder if he already knew, but couldn’t talk about it.

Enslaved people in Suriname came from different parts of western Africa. None of them were permitted to speak Dutch because colonialists didn’t consider them worthy of the language. In order to communicate with each other, they created their own, called Sranan Tongo, or Surinamese Tongue.

In African culture, as with others outside of Europe, history and folktales are passed on by word of mouth. For the many people who are descended from the enslaved, that loss of language, combined with trauma and shame, resulted in the destruction of our generational knowledge.

While I was gaining a more complete sense of my ancestors’ stories, I also acquired insecurities that didn’t exist before, which I believe is because I present as East Asian, without a hint of my African heritage. If I wear a traditional Chinese suit, no one would question it, because those clothes would match my face. However, if I chose to wear a traditional African outfit, I would feel compelled to provide a reason, even if I wasn’t asked.

A sense of not truly belonging was coiled within me, waiting to reveal itself. My hesitation when asked if I was proud to be Black led me to examine where that insecurity had come from. No one had made me feel that way through their actions; quite the opposite.

But how can I be Black man when I obviously don’t present as one? Looking at photos of my father and his seven brothers is like reviewing a paint chart, with a gradient of skin tones; Dad was the lightest one.

An Ancestry DNA test showed that I am 50% Chinese, with 30% from Cameroon, Congo, Benin, Togo, Ivory Coast, and Ghana. The rest is Ashkenazi Jewish and European.

So, how should I describe myself?

I’ve heard some of the mixed-race Indigenous people I know self-describe as, for example, Cree and German, rather than half-Cree and half-German. They regard themselves as a combination of their parents, not a diluted version of them.

Given both my ethnic and cultural background, I am now comfortable describing myself as Chinese-Caribbean and Afro-Caribbean.

And, as I recently discovered, I am also proud to be Black.

By

By