Who am I?

My mother’s heritage was Chinese, and I know the names of dozens of her ancestors, all the way to the mid-nineteenth century. For most of my life, the only things I knew about my father’s ancestry were his parents’ names and dates of birth, that they were born in Suriname (also formerly known as Dutch Guiana), and they were Black.

My features are predominantly Asian. So, who am I?

The person I think I am now is very different from who I thought I was a week ago. In February 2021, after a brief conversation with someone I didn’t know, I gained two generations of ancestors, and I met the last enslaved person in my family.

===

My parents were from Guyana (British Guiana) and emigrated to England in 1964, the year before I was born. We lived in a London suburb called North Finchley. Even though it was solidly middle class and predominantly white – our MP was Margaret Thatcher – the local population was still ethnically diverse. My school friends were either English, Italian, Greek, Indian, South African, or Jewish.

My family’s celebrations were adapted from Guyanese traditions. Christmas breakfast was garlic pork, which involved Dad soaking slabs of fatty meat in white vinegar, garlic and herbs for several weeks beforehand. From the beginning of December, I would be salivating in anticipation. Festive dinner was roast turkey with Mum’s fried rice and chow mein, followed by Dad’s rum cake.

In our home, Guyanese culture was reflected in the food we ate, the loved ones we socialized with, and the huge smiles that resulted from the supremacy of the West Indian cricket team, especially when it was embarrassing England. This was particularly sweet because the Windies’ captain during those rampant years was Clive Lloyd from Georgetown, where my parents were also born.

Our family and friends were a variety of colours and ethnicities – Black, white, Chinese, Indian, Portuguese – but they all spoke with the same heavily-accented Guyanese patois that never left them, even four decades after they moved away.

My parents affectionately referred to their birthplace as “B.G” (British Guiana), or “home”. Despite that, they never returned after they’d left.

None of their generation talked about Guyana’s history, and I assumed this was because they were never taught it. Dad was proud that he’d learned Latin at school, but it was odd he knew nothing about slavery in the region. Likewise, my history education in England covered Britain’s glorious sovereigns without discussing how they came by their wealth.

I knew my grandparents were from Suriname, hence our Dutch last name, and old photos of Dad and his family showed various tones of dark skin. It didn’t occur to me until well into my thirties that I probably had ancestors who had been enslaved.

You could write a book about my mother’s side of the family. In fact, someone pretty much did exactly that. One of my cousins researched and compiled a binder full of dates, names and stories of several generations of our Chinese ancestors. Another cousin created a detailed tree that traced family to China in the 1860s.

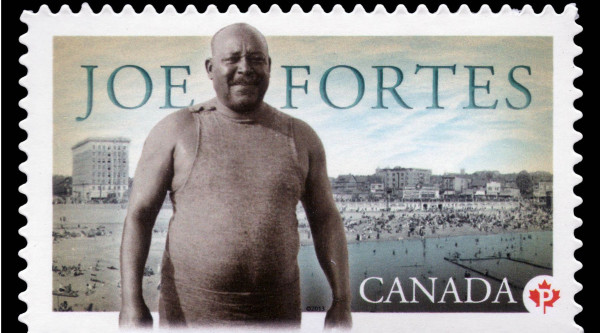

Nigel Gordijk’s parents on their wedding day in Guyana (British Guiana). His grandparents, standing next to the groom, were from Suriname (Dutch Guiana).

However, other than the most basic details, I knew nothing about my paternal grandparents.

I felt a sense of regret because I hadn’t been inquisitive when I was younger, and I’d never asked my grandmother about our family’s lineage while I had the chance. Antoinette Wilhelmina, the last of my grandparents, died when I was 15.

This made me feel vaguely incomplete. My Chinese heritage was well-documented, but my Black legacy was a blank page.

In 1996, I came to Canada to visit family, and that’s when I met my wife Cheryl in Kitchener, Ontario. We married in 1997, lived in England for 10 years, and then moved to the small, rural town of New Hamburg, Ontario in 2007.

As the settlement’s name suggests, many residents’ families originated from Germany. Shortly after I immigrated, I asked someone how long their family had been here, and he proudly answered, “Five generations.” It stung that he knew so much about his lineage while I knew so little about mine.

After I started an Ancestry.com account a few years ago, I found that several cousins had done so, too, but none had managed to go back further than our paternal grandparents. I reconciled myself with the idea that this was much as we would ever know about our family’s past.

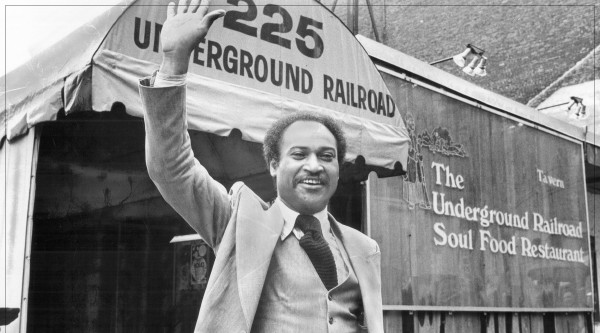

Nigel Gordijk’s father, wearing his national service RAF uniform, and his seven brothers.

In December 2020, journalist Jasmine Mangalaseril interviewed me for her Grand magazine column about people’s memories of food from their childhoods. January’s profile featured chef and ByBlacks.com contributor Teneile Warren, and I sent her my congratulations when it was published. We talked about the dishes that each of us had chosen, and it was clear she’d discussed mine with Jasmine as she exclaimed, “Oh, you’re the garlic pork!” I also told her about my background.

On February 9, 2021, Teneile suggested I contact Peggy Plet, a Surinamese writer and researcher whom she’d just met in Kitchener that week. I sent an email and asked to buy a copy of her biography of Surinamese inventor Jan Earnst Matzeliger. I mentioned that my grandparents were also from Suriname.

Peggy immigrated to Canada 20 years ago, and she lives just a few miles away from me. As luck would have it, Peggy is also a genealogist. She offered to help me find my ancestors, so I sent her what little information I had.

Just five days later, on the eve of Family Day, Peggy sent me the perfect gift: The past I never knew I had.

When I read the nine pages of notes and newspaper clippings that she’d emailed, I was astonished. Peggy hadn’t identified just my great-grandfather, but also his enslaved mother, my ancestor, Betje.

===

Betje was born in Suriname in 1822.

She was owned by multiple people and sold several times. Anna Pieternella Groenhout, her final owner, was a Black woman, a former slave who was freed in 1839. Two years later, she bought my ancestor, who worked as her housemaid.

Betje had six children. One child died shortly after birth, and one was sold to another owner. Betje bought the freedom of the remaining four, including my great-grandfather, Frederik. These were the first of my ancestors to carry the last name Gordijk.

Betje later bought her own freedom, too.

Frederik Gordijk had four children, and the third, James Johannes, was my grandfather. James married Antoinette Wilhelmina Sanchez, the only grandparent I ever knew. The couple moved to Guyana, where my father, Sylvion Frederick, and his seven brothers were all born and raised. After Sylvion married my mother, Edmay Keturah Chan, they emigrated to England, along with his parents. James died in 1964, and Antoinette passed away in 1981.

===

I read the connections between dates, names and events, over and over and over. I excitedly shared them with close friends and family. However, I didn’t start to feel the impact of all this information until the next morning.

On Family Day, in the middle of Black History Month, I shared my newfound heritage on social media. As I typed the details into tweet-sized chunks, there were several times when I had to pause and take a deep breath.

Even though I’d had strong suspicions my ancestors were enslaved, that somehow felt abstract; learning the name of an actual relative made it personal.

Tears started to well up.

My friend, Jana, responded to my Facebook post and referred to my vocal, public response to local acts of racism. When I read her comments, the dam burst.

“What a fascinating back story and what an incredible gift to know it,” she said. “I imagine it’s a lot to take in and it’ll need time to settle in your bones. I know you’ve taken a lot from people for being outspoken on local issues this past year. I can see your ancestors all gathered, watching you now. This is the healing of those silenced generations.”

She added, “I really think this is how intergenerational trauma gets healed.”

After I’d composed myself, I replied that I wouldn’t describe what I was experiencing as trauma, and I don’t think my dad had carried that burden, either.

But then it occurred to me: What if it was his burden? Maybe not talking about the past and not asking questions is how my family avoided the pain of thinking about our enslaved ancestors. Perhaps they experienced shame, or even guilt?

Peggy told me later that this wasn’t unusual.

“I think that goes for a lot of families, not just yours. It’s not only because you didn’t ask. Shame is a lot of what’s contributing to these feelings.”

She warned that I’d experience a range of emotions as I dealt with the recently-discovered details of my ancestry.

“You’ll see as you go through this journey you will go through several stages,” she said. “So, now it’s the shock because you didn’t expect to find anything, and then you find the information, and then there’s happiness, and then comes the anger part, so there’s different stages. Just take your time and let the emotions come.”

Peggy helped me understand some of the context of Betje’s life, and what drove her. “As long as there has been slavery, there have been people fighting for their freedom.” They would either run away or buy themselves out of captivity, a practice called manumission.

For Betje, it was important that her children shouldn’t grow up enslaved, which is why she paid for their freedom. Her own manumission, in 1862, came just one year before emancipation. According to Dutch law, any person who was emancipated in Suriname in 1863 still had to work for another 10 years. Enslaved people were buying their freedom right up to the day before emancipation to ensure that they were truly free.

After Betje’s children were manumitted, they may have stayed with their mother. Perhaps she and Groenhout had some sort of an arrangement, as the older children could do simple chores around the house, such as fetching water, keeping the yard tidy, and tending chickens.

As a housemaid, Betje probably wasn’t confined to her owner’s home. While her work might have included house cleaning, laundry and cooking, it’s possible her owner used Betje as a source of income, too. She may have been sent out to sell baked goods or eggs, for example, with the mistress telling Betje how much money she expected her to bring back. Betje might have charged as much as she could for the goods, and then returned with the expected funds. She would have kept anything extra, and she could have earned additional money by doing laundry for customers in town, too.

“Enslaved people were creative in finding ways to earn money to buy their freedom,” said Peggy.

I would love to learn what happened to Betje after she became free, but right now I’m processing everything I recently learned.

I hope we’ll be able to trace my grandfather’s lineage further, plus there’s also my grandmother’s saga to explore. They have so many stories still to be discovered; stories of desperation and determination, tragedy and triumph.

And now, thanks to the kindness of strangers, that’s my story, too.

By

By