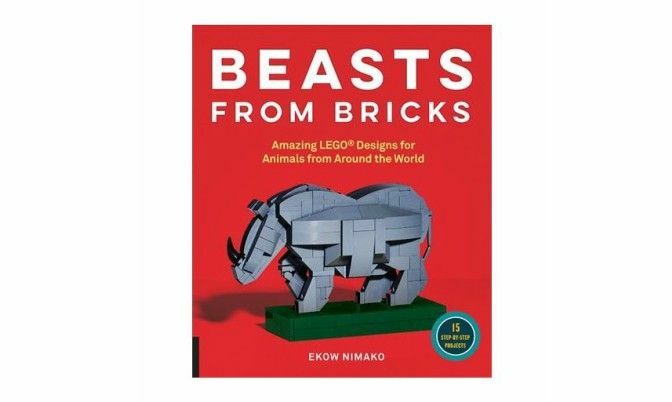

Appealing to Lego fans, both young and old, his book Beasts from Bricks is a colourful guide on how to produce miniature Lego sculptures and, at the same time, serves to motivate readers to care more about the animals from different continents that have inspired Nimako’s designs.

Nimako began using Lego professionally in 2013 and is well known for Silent Knight, a sculpture of a seven-and-a-half-foot white Ontario Barn Owl in flight, which captivated onlookers and was commissioned by the City of Toronto for the 2015 Nuit Blanche arts festival. I spoke to Nimako about the book, his motivations and his process for using his fine art skills in capturing the essence of animals in ways one would not expect possible by clicking together Lego bricks.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

Why do you build animal sculptures with Lego?

I love animals. They are very awe-inspiring. It’s also a great challenge to capture animals in that way that I do. I remember when I made my first cat, I went online to see what else is happening with cats and I honestly wasn’t impressed. That was what drove me to improve my process. I want to actually make a cat that looks like a cat; I want it to capture the grace of a cat. It starts with the parts. Often, people will focus on using the literal bricks from Lego as the main method of building, but there’s so much texture to the different Lego parts they have out there, so many bends, curves and slopes. Why should I feel limited to use the rigid cubular bricks? I want to use all the curved parts and I want to capture the curve of the eye and the curve of the ears and the daintiness of the paw, and I want to capture all of that and I know that its possible. More so, I know I am capable of doing it. I’ve just got to push myself to do it. It's a very unique challenge building natural forms using Lego. That’s what pushes me.

How did Lego become your go-to medium for sculpting?

I fell into it. I would always use the material as a child. It was my favourite thing to do with the exception of drawing, but I didn’t get into drawing until I was a bit older, maybe around eight or nine years old. But with Lego, since I was four-years-old, I’ve been playing with it. For a period, I wasn’t using it between age 13 and my early 20s. Then Michael Bay’s Transformers live-action movie came out in 2007, and I had the compulsion to create based on the inspiration of my favourite childhood cartoon coming to the big screen. That rekindled my joy for building. That was about 2007, but it wasn’t until 2013-2014 when I really started perceiving Lego as a medium for making art because I spent three years in art school, studying sculpture and drawing. I really got into sculpture at that point, but wood and metal did not resonate with me the same way Lego did. Plus, I saw there were other creatives using Lego in a sculptural capacity and making a living with it. That told me it was possible, which was really important for taking on this endeavor.

Did your childhood influence this book in any other ways and did other children in your life also influence this book?

Yes, to a certain extent. My two daughters influenced my work in general and probably a bit more of my personal body of work, my fine art, which focuses on sculptural black children. But kids give me a reason to buy Lego. I would buy it for my nephew, for my niece, and I would also buy it for my daughters. I would have Lego in my hands and we would play with it together. This kept it alive, but not so much directly related to the book itself, but related to my kids inspiring the whole Lego experience that I’m involved in.

From Beasts from Bricks by Ekow Nimako, published by Quarry Books/Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc. Photography by Janick Laurent, J Studio © Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc. All rights reserved.

What was your inspiration for creating Beasts From Bricks specifically?

It was serendipitous. I wanted to make artwork that was a bit more accessible to people because my fine art, whether monetarily or conceptually, isn’t so accessible. Aesthetically, you can look and appreciate its value, but if you want something to take home, it's a little difficult. So I started creating a series called the miniatures. I would take larger animals and make them on a miniature scale and challenge myself to use fewer parts, but still capture the same life and fluidity that I would bring to my larger, more complex pieces. So I took the miniatures on commission basis. They’re on my website; I hadn’t showcased them anywhere, but they had a life on the web. I have a photographer, Janick Laurent, and he’s amazing. He’s a family friend as well and he’s pretty much up to this point shot most of my work. I had this idea when he was shooting the miniatures to create a storybook. I’m a writer as well, so I wanted to create these fables in the kind of folklore, oral tradition of my ancestors and my people; my family is from Ghana. I wanted to tell these stories about animals and pass on this proverbial wisdom through folktales, and I would illustrate it with the miniatures and have Janick shoot them. But before that came to be, Joy Aquilino reached out to me from Quarry Books and she had seen my miniatures and said she was interested in putting out a book, but an instructional book featuring my miniatures. It took me a little bit of time to adjust to the concept of making my work that accessible to the point of giving instructions to something that was initially my own creation and something that was, in terms of my process, very private. But after some thought, about six months later we decided to go ahead with the project. Now people can create their own miniature sculptures for their desktops that still carry that aesthetic that people really seem to like about my artwork.

What’s your overall thought process for translating animals into Lego sculptures?

It starts with photo references. I will hop on Google, look up the animal and start studying it, following its nuances, and then I would start thinking about the palette. There’s only so many colours that Lego offers that are translatable as natural colours that animals in nature actually have. Some colours are a little closer to the animal’s natural palette than others. I think about the palette and if I have the parts on hand, I will proceed to start tinkering around. It’s all very trial and error. I don’t use blueprints or designs for anything. The only time I use blueprints or designs is when I’m using a larger sculpture that requires an armature — a skeletal framework used often with large sculptures — fabricated by a professional crafts person, then I need to have designs to help them create something that will fit with the sculpture. But when I don’t need an armature, I don’t draw out anything, I just start playing around, putting things together, looking at parts and trying to visualize what could be. Clicking things together usually starts with the head because that’s often the most difficult part to capture on a small scale because you can only use 10 Lego parts maximum or a few more if you’re making a miniature. Otherwise it starts getting too large and becomes not so much a miniature anymore. That’s usually the hardest part: starting with the head. Once I have the head, the rest falls into place and I start tinkering.

From Beasts from Bricks by Ekow Nimako, published by Quarry Books/Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc. Photography by Janick Laurent, J Studio © Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc. All rights reserved.

There are 15 projects in this book to build animals from the land and sea. How did you choose which animals to include?

Trial and error mixed with my interests. There were certain animals I definitely wanted to put in and the rest were regional. It’s difficult to come up with animals in the Arctic; there are not a whole lot of options. They’re all herbivores or grazing animals or something along those lines. There were a couple animals that didn’t make the final cut because I couldn’t get a design I really liked. There was a Canadian Moose for the region of Canada, but then something just didn’t click — no pun intended. I just had to scrap that project and move on to another animal. Instead, I chose the Kermode Bear from British Columbia to rep Canada. It has a really deep significance to Indigenous people of this country.

What’s your favourite beast in this book to build?

I don’t have a favourite in terms of build because the building process is really arduous. I find a lot of joy in building; it’s where I find a lot of peace, but there are also a lot of challenges and frustrations. In terms of aesthetics, the hippo is my favourite. I just really love the way the hippo, seemingly floats below the surface of the water. The pictures that I would see of hippos, oftentimes they are in the water, sometimes they are above ground. They are such bulbous creatures, and so when I built this sculpture and it looked so buoyant and floating, I really enjoy that. And I enjoy the white-tailed jackrabbit too because it has the best conveyance of motion. That's what I really, when you see that fluid nature. The sculpture of the jackrabbit is, in my mind, leaping away from a predator. That moment where it lifts its head up, its ears perk and then it’s gone. That first leap when it jumps, it propels itself with its huge back rear legs, that’s what I wanted to capture. Lego is very cubular, it's very geometric, so often when you see things made with Lego its more architectural, vehicular. When you start getting to natural forms, sometimes it can be a bit rigid. So its always my purpose, whether it's with my miniatures or whether it's with my fine art — like the figurative sculptures — to always undermine the rigidity of Lego by making everything look so smooth and fluid.

You’re well known for Silent Knight, the owl in flight built for Nuit Blanche. How large are your miniature beasts compared to Silent Knight?

They are quite small in the same what that a mouse is compared to a human. Silent Knight is massive. It reaches almost 8 feet tall from the tip of its wings to the ground. These miniature sculptures don’t go any higher than five or six inches.

Photo credit: Janick Laurent

Is it more complex to build smaller or larger Lego sculptures?

It’s hard to say which is more challenging. If I had to choose, larger is still more complex because there are more options. There’s more stress when you have more choices and more options. At the same time, that doesn’t mean there isn’t challenges with the smaller ones because there are less options.

It could take hours because there’s only so many parts I can use. Lego only gets so small and there are only so many options. The interesting thing too is that Lego keeps making new parts, and I have to stay on top of it, scouring the website I use to order parts and seeing what else is out there. There are standard parts I should always have on hand if I want to get anything done. There are certain parts I just need for sure in every colour or I know that I will be stunted at every corner. I have to keep alert as to what’s new and what’s out there.

What about working with Lego brings you joy?

Discovery. No sculpture I’ve ever made is the same. My process has so much discovery and so many improvements wired into it, I won’t do it the same way twice because I’ll make something one month and then five months later, if I want to make the same thing, I’ll find another way to do it, and that other way is usually an improvement. That may be because I’ve discovered new parts or a new way to achieve something.

Who did you have in mind, kids or adults, when you created these projects?

Kids just love them. That’s the beauty of art, and especially representational art, the kind of art I make, which means art that is representative of something that already exists in this world and is recognized as such, as opposed to stuff that is more conceptual or abstract. At the Black Arts & Innovation Expo, a young man about seven or eight years old with his father, he loved the lion that I had built. He ended up convincing his father to buy it for him. At the same time, I know there are adult fans of Lego who would go crazy over these kinds of sculptures. The book is for everybody, whoever likes it. I want to make stuff that people can buy and not just go to an art gallery and admire but can’t necessarily take home. I want there to be access to my art, so I’m going to make these small ones. But just because of my aesthetic they are still going to turn out looking very artful. Note: Defer to Lego’s age limit for the appropriate age for children’s use of the product.

From Beasts from Bricks by Ekow Nimako, published by Quarry Books/Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc. Photography by Janick Laurent, J Studio © Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc. All rights reserved.

You tell us in the book about each animal, their habits, their physical traits, the dangers they face. You even tell us their scientific name. Is there anything about these animals that you learned that surprised you?

Some of the more endangered animals, the walrus for example, I didn’t know the Walrus was so hunted. There are sanctions and protocols set up to protect it. Baby harp seals were also hunted in the thousands. Those numbers seem astronomical to me. That was a bit staggering to find out. You start doing research into animals and you see how much the imbalance that humanity has struck up with the natural world. It’s kind of disheartening. So its good to have those facts in the book too because any way you can help spread the word about endangered species or at-risk species is definitely a good thing.

A lot of these animals, most people probably wouldn’t think about them on a regular, or even irregular basis, but you put them in the book and suddenly you’re thinking about them.

Yes, especially young people because that’s where the future lies. It's hard to get things out of adults head’s sometimes, especially if they feel entitled, which is often the case when it comes to humans and the natural world. There is this sense of entitlement to the natural world because of humanity’s intelligence and dominance or lust for dominance. So when you can soften that a bit by playing with a material like Lego that is so ubiquitous and so charming, it's a positive thing.

Photo credit: Akbar Ahmad

How long did it take you to design these animals on average?

I usually log all my builds, but off-hand, it took me eight to 20 hours each.

Is this book, in part, insight into the artist’s process as much as it is instructional?

To some extent. That was a bit of a fear for me when it came to agreeing to do this book. My process is pretty protected; I’m not typically showing how I do things, even though I appreciate when other people do because it helps give me some insight on techniques. But my friend Janick the photographer, he said, “I used to think that way too when it comes to my photos, trying to be guarded about what I’m doing, but you’re always onto the next thing man and you’re always improving.” It’s good to release things and be cathartic and let some things go and say, here this is how I do this and now you can do it too. When it comes to Beasts From Bricks, some of the animals I’ve re-created new versions of them and they are different. I’m always changing things, and improving. Now, I think it's a good thing to share.

Now that the book is out and physically in your hands, how do you feel?

I feel a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment. Creating a book, like I mentioned, is something that I really wanted to do. I remembered I was in a bookstore and I saw this book called Beautiful LEGO by Mike Doyle. It's a great book that has a collection of different builders from all over the world, building different things with different categories that the author set out. He has included some of his own pieces in there too, but it’s more like an anthology of different builds. I thought the book was amazing and that I need to be in one of these books. Four months later, I got an email from Mike Doyle asking me if I wanted to be in his sequel book. I have three images of sculptures in Beautiful LEGO 2: Dark. That was really serendipitous. This is setting me on the path. The next thing I wanted to do was a folktale, fairytale book illustrating it with my miniatures, but then I got an email from Joy Aquilino asking me if I was interested in doing Beasts from Bricks. It wasn’t exactly what I was planning to do, going the instructional route, but it is a good move.

After Beasts from Bricks, do you envision yourself doing another book?

Yes. That’s definitely within my sights and I’m excited. There’s definitely an opportunity to do more and there’s so many animals out there and so many different ideas I could follow. I have been commissioned to do architectural builds as well, and I have a lot of fun doing that. So who knows what my future holds.

My focus is always on my fine art. That’s the main thing I want to do and build and expand on, my ongoing exhibition, Building Black. That’s the most important thing that I do. Building Black (first launched in 2014) is my own exploration into black identity and mythology and morality inspired by like surrealist art and also Ghanian metaphors and proverbs. Anything else that can help support that, other books that can get people excited about the things I am able to do with Lego, that’s all very supportive and amazing.

The layout of your Instagram is pretty cool. The layout seems like a puzzle, the individual posts fall into place to create a bigger picture.

I recently started doing the large pictures grids. It’s great to throw up stuff, but sometimes I go through phases. I’m becoming increasingly reclusive and I don’t always feel like putting my stuff out there. I’m very critical about modernity in general, as much as I love human innovation and technology. As much as I think it's a great tool, it's important for me to post and get more followers and people want to know, there’s another side of me that's really indifferent too. I know it's a business, but I don’t feel like telling every day what’s going on with me. I don’t want to feel obligated to report to the world what it is I’m doing. So it’s tough. It's a paradox. I have a love-hate relationship with social media.

Are you becoming more reclusive on social media or in general?

In general. I don’t go out as much as I used to. I don't drink. My work is labour intensive. My studio is in my home and the more that I am outside of my studio, the less work I’m getting done and I have a lot of work to get done. I am not at a point in my career where I have my work circulating in galleries around the world. My work is sought after and right now, it’s my work phase. I’m past 30. Between 30 and 60, you’ve got to work so that by 60 if you want to relax for the rest of your life and take care of your family. That's who I am. I really do want to take care of my loved ones. That plays into me being reclusive. You’ve got to work, especially if you’ve found what you love doing too. You’ve got to put in the hours. People expect things, they expect the world, they expect all this stuff, but you’ve got to put in the work. If you’re a writer, you’ve got a lot of writing to do. And if you’re an artist, you’ve got a lot of art to make, so go and make it.

Beasts from Bricks will be launching at A Different Booklist, 779 Bathurst Street in Toronto, on Sat. Nov. 11 from 2-4pm. Nimako will be available on site for a book signing.

Go to ekownimako.com for more details.