Curated by Karen Carter and Belinda Uwase, the 19 portraits in the exhibition celebrate Ethiopian patriots, who, using only spears, swords and shields, defeated the modern Italian army, which attempted to conquer their land twice.

The first attempt was in 1896, when Ethiopian heroes and heroines resoundingly defeated the invading Italians at the Battle of Adwa. The second attempt took place in the 1930s when the patriots paid a huge price to protect their country from colonialism. As a result of this, Ethiopia remains an independent country that has never been colonized.

“I believe, photography should not only be about taking good pictures but also about telling stories. So great photos should tell stories that create a lasting impression on the viewer,” says Dawit. He goes on to explain the intersections between photography and storytelling, and what powerful images mean to him. “You tell stories that you are familiar with. Hence, great photos are well-researched and very much connected with the photographer, so that they can be easily connected with the viewers as well.”

Raised in a society that values history and oral literature, it is no wonder Dawit became a storyteller. “I grew up listening to religious stories and Ethiopian history being told by my parents. Besides, I used to take part in Patriots and Martyrs Days celebrations since childhood. So the story I tell through this series of photos is very dear to my heart.”

Dawit says he started practicing visual storytelling at an early age, when he was an elementary school student. “That time, my favourite drawing ideas were national heritages and animals endemic to Ethiopia.” Since then, he has been longing for an opportunity to document and share with the entire world the history of his ancestors who ensured their country’s independence.

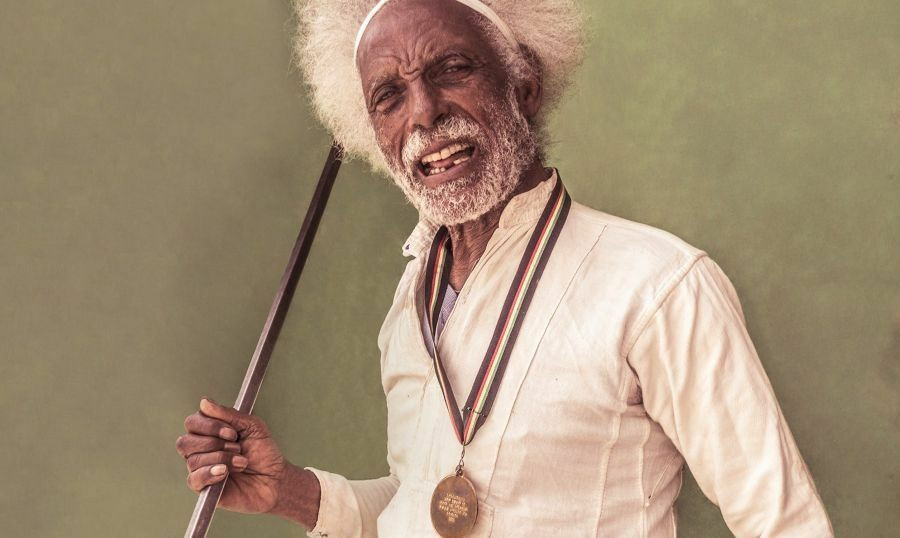

Dawit took the photos in the exhibit on March 2, 2015, in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia during an annual event to commemorate the Victory of Adwa. The diverse collection of portraits in the exhibition presents the descendants of the patriots wearing military uniforms, traditional attires, medals and weapons which all serve both as cultural and historical touchstones.

The caption under Patriot Abate Gashahun’s portrait reads, “Everyone must die, but dying defending your country is an honour. This uniform, the medal, and the flag are what keep my father alive in my heart.”

The photos also affirm the significant role that Black women held in world history. The caption of a portrait of a woman patriot called Mamitu Meheretu says, “I was a baby when the Second Italo-Ethiopian War began. My mother travelled with my father’s military troop to provide food, supplies and other basic support on the battlefields. She used to carry me on her back and she took me with her to the battlefront as she could not leave me alone.”

Describing his experience of documenting the portraits, Dawit says it was not a challenge for him to take such powerful pictures with real expressions and genuine emotions because the subjects were very natural and genuine.

“Just by looking at the photos, you can tell how I felt when I was taking them. Other than knowing the history, I was emotionally connected with my subjects just by being around them.”

He adds, “As a photographer who sees photography beyond clicking the camera button, it was one of the remarkable phenomena in my professional life.”

“The majority of the patriots were actively performing shilela (patriotism songs) and qererto (warriors' chants and songs), while some of them were calm. But the unifying feelings they all shared in common were gratefulness, freedom, and pride,” he explains, overwhelmed with emotion.

Dawit stresses, Black people have been misrepresented by most Western photographers so far, as most photos by the Westerns depict poverty and backwardness. He stated that as a photojournalist and as a portrait photographer, the most important ethical rule for him is to give the greatest respect to his photo subjects. “Most Western photojournalists incline to depict the downsides of Africa or Blacks in general. This is because there is a loose connection or no connection between the photographers and their subjects,” he asserts.

“This notable history doesn’t merely belong to Ethiopians. The entire Black community across the globe should know, own, tell and celebrate it,” he emphasizes the aim of the exhibit. He further stresses that the purpose of such stories should not be for the sake of sticking to the past; it should be an inspiration to lift up Black peoples’ spirits and to tell others about the untold stories.

He insists Black photographers should be encouraged to share their perspectives of their origin stories for the world to have a balanced and complete image.

Finally, Dawit says he is forever grateful for the Black heroes and heroines who fought off colonialism and continue to be an inspiration to this day.

Go to www.bandgallery.com for more info.

By

By