The saga begins when Mary-Louise McCarthy Brandt, a 6th-generation Black woman from Fredericton, New Brunswick, hears about a newspaper ad from her mother during the early 1990s. The advertisement, penned by a concerned woman, highlighted the alarming erosion of the Black graves that were abandoned during the construction of the Mactaquac dam by New Brunswick Power. Shockingly, bones were washing up on the shores.

One of those graves belonged to McCarthy Brandt’s great-grandfather. Some were local carpenters and farmers.

How Did This Happen?

After conducting an intensive 6-month investigation at the Provincial Archives, McCarthy Brandt uncovered evidence that those involved in establishing the dam were well aware of the existence of a Black cemetery that the dam expansion would submerge.

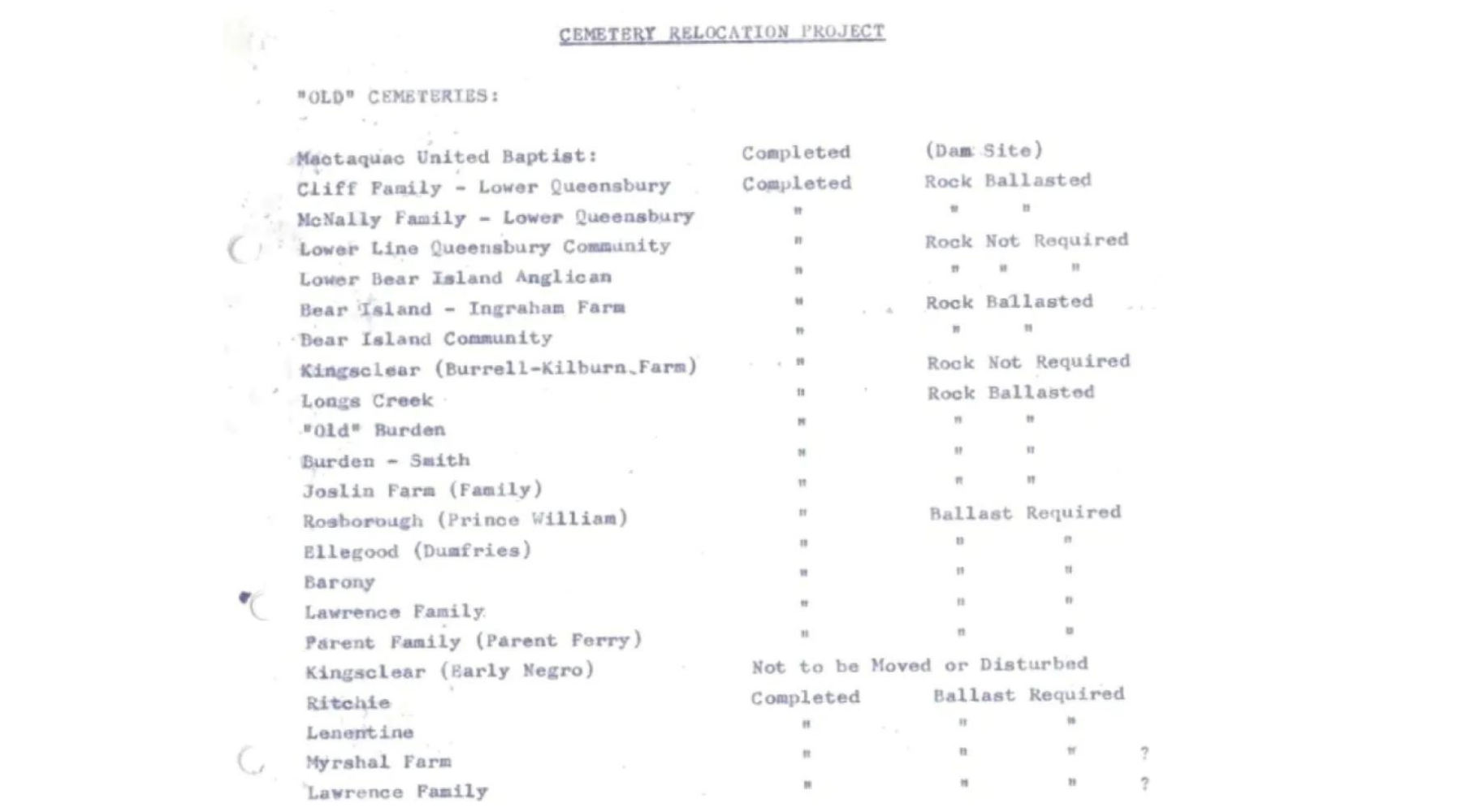

In fact, as there were so many cemeteries that would have been impacted by the dam, there was a “cemetery relocation project” which made a list of all the burial sites that would need to be moved. The Negro cemetery is the only one on that list with instructions “not to be moved or disturbed”.

In the absence of public pressure to preserve the Negro graves, NB Power quietly allowed about fifty to sixty graves of Black folks to be swallowed up when the water levels were raised for the dam.

While NB Power allowed the Negro Cemetery to be flooded, they did erect a small stone to mark the site. Through her research, McCarthy Brandt discovered letters from 1968 discussing the stone and negotiations surrounding the amount of text and its associated cost. A local company quoted NB Power $275 but the archival letters show NB Power was unwilling to pay that much. They negotiated a lower price with less writing on the stone.

“I think they paid maybe forty or fifty dollars for the stone,” says McCarthy Brandt. “They put a saying on the top, ‘herein lies the original descendants of the Negro community of the Kingsclear area’. Then they just wrote 10 or 12 names and only surnames.”

McCarthy Brandt returned to visit the memorial stone multiple times, accompanied by her cousin David Payne, a researcher from Maine, who assisted her in uncovering more information.

Participants in the 'cemetery relocation project' made a list of cemeteries to be moved so they wouldn't be flooded by the St. John River. (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick)

Decades later, that stone would go missing, and its discovery would bring McCarthy Brandt even deeper into this story.

McCarthy Brandt shares, “In the early 2000s, after a new twinned four-lane Trans Canada Highway had been built, some houses were built that bookended the cemetery. The old Trans Canada Highway was becoming prime real estate with waterfront footage. The two men that owned the properties didn't want that cemetery which was overgrown and an eyesore looking like that. They decided to take over the cemetery and started cleaning it up. I was going every year or so to check if the stone was there and then I went to check and the stone wasn't there. I went back to my car and I didn't know what to do. And I thought, ‘Oh my God, the stone's gone. What am I going to do?’ And then I decided, I'm going to knock on doors. The very first house I knocked on, the guy had the stone.”

That guy was Laurie Jordan and had the stone in his garage. Jordan reassured McCarthy Brandt that he took the initiative to recover the stone with the assistance of a friend who had a mini excavator and that he intended to start a nonprofit to clean up the cemetery. Jordan asked if McCarthy Brant wanted to be on the committee.

“And I said, absolutely. I was on that committee, and it's called the Kingsclear Kilburn Community Cemetery Committee. I remained on that committee for 20 years advocating for the rectification of the stone.”

In 2020, Jordan passed away, and his wife, Twyla stepped in and helped McCarthy Brandt and the committee by engaging with NB Power on how to properly memorialize the Black graves under the Saint John River which flows to the Mactaquac Dam.

McCarthy Brandt along with the committee cleaned the original stone and placed it in front of the Kingsclear Kilburn Cemetery with flags beside it. However, they felt that this alone was insufficient, as the original stone was poorly executed.

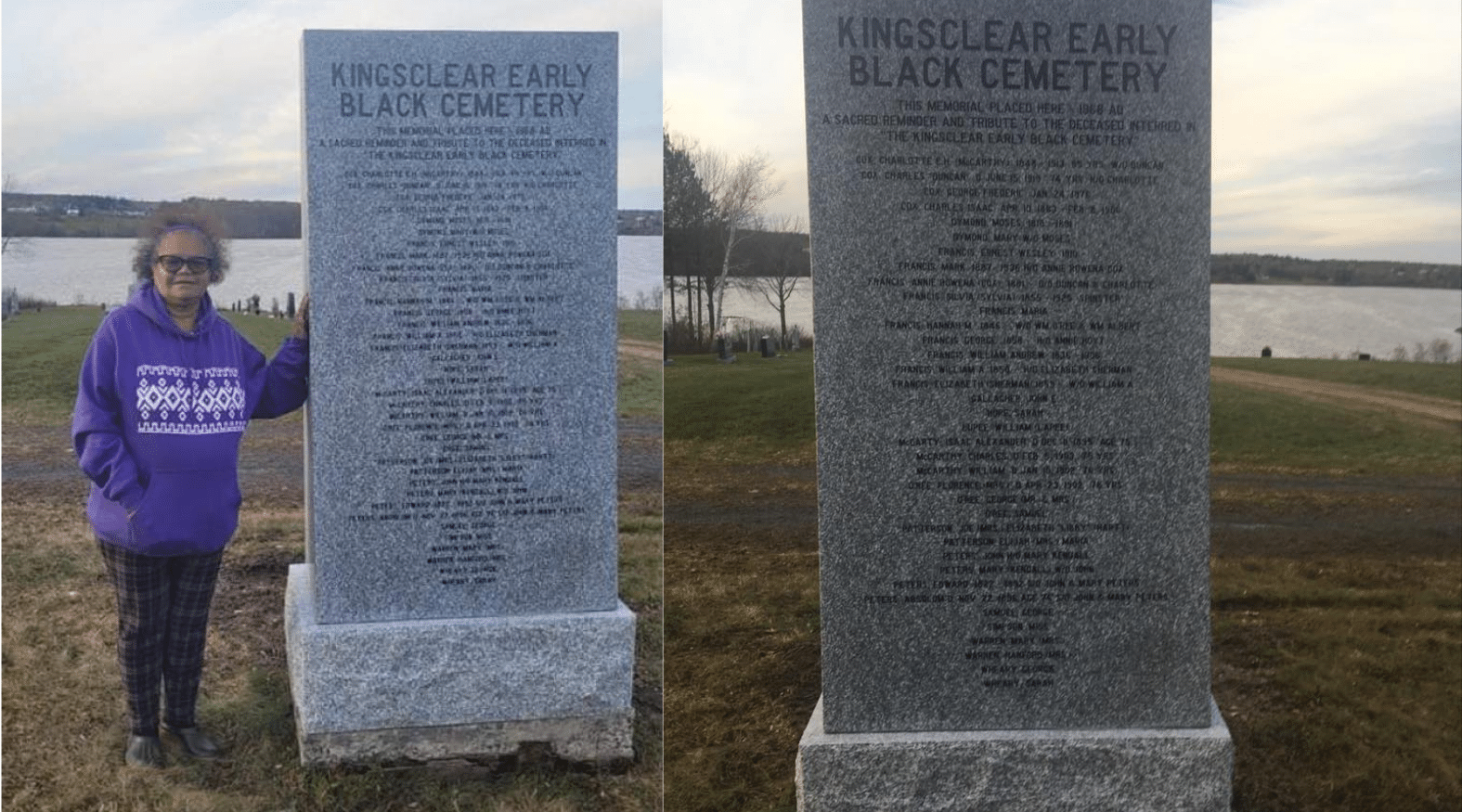

Finally, in 2021, NB Power agreed to put in a new stone with the recommended amendments from McCarthy Brandt costing around $7,000. “The team at NB Power worked with myself and my cousin and researcher, Jennifer Dow, to get the proper names of the deceased.”

The new stone stands high at 7 feet tall and has nearly 50 names on it, which McCarthy Brandt and Dow found through their extensive research.

Today, McCarthy Brandt is still in talks with NB Power as she wants a public apology for what happened to her ancestors’ graves. “I don't have the benefit most people have of going to a cemetery and seeing their grandparents. I don't have that, because they're under the Saint John River/Mighty Woolastoq.”

Despite NB Power's willingness to replace the stone, communication has now halted, seemingly due to their reluctance to issue a public apology. McCarthy Brandt remains hopeful that the newly appointed CEO will recognize the importance of accountability and offer the apology she and her ancestors deserve.

The work McCarthy Brandt did to properly memorialize the Old Negro Cemetery became the subject of her Ph.D. dissertation, where she shed light on the stories of six overlooked Black cemeteries in New Brunswick. It also became the foundation of the REACH NB organization.

“I realized once I wrote this dissertation I couldn't just stop thinking about my ancestors and their requirement to be buried in peace and with respect. I decided I was going to start a nonprofit. REACH’s name has to do with Remembering Each African Cemetery, but actually REACH has two major focuses. The first is to reverse the erasure of Black history in New Brunswick. The second is to document, find and repair lost and forgotten Black cemeteries. In fact, my wish is to get a national database of Black graves in Canada, much like the military database. We've been in touch with the provincial archives and they said they want to work with us and help us store our data, but we haven't given them anything yet. We're still working on what that relationship looks like.”

McCarthy Brandt has been informed about the existence of at least 10 additional neglected cemeteries within the community. Her participation in the Northside Heritage Fair has made her a trusted resource, with people approaching her booth to share information about more cemeteries or burial plots containing Black individuals. “They feel like they have permission to talk openly about our Black community, and they sit and they tell me, ‘Oh, do you know there's someone buried here? And I know there's three children buried here.’”

“I just feel that as a Black woman, I have to tell our stories and I have seen that there's an erasure and a vacuum of Black history. I'm trying to promote, inform and educate academics and politicians to know that Black history is New Brunswick history.”

To learn more about REACH: https://www.reachnb.com/

By

By