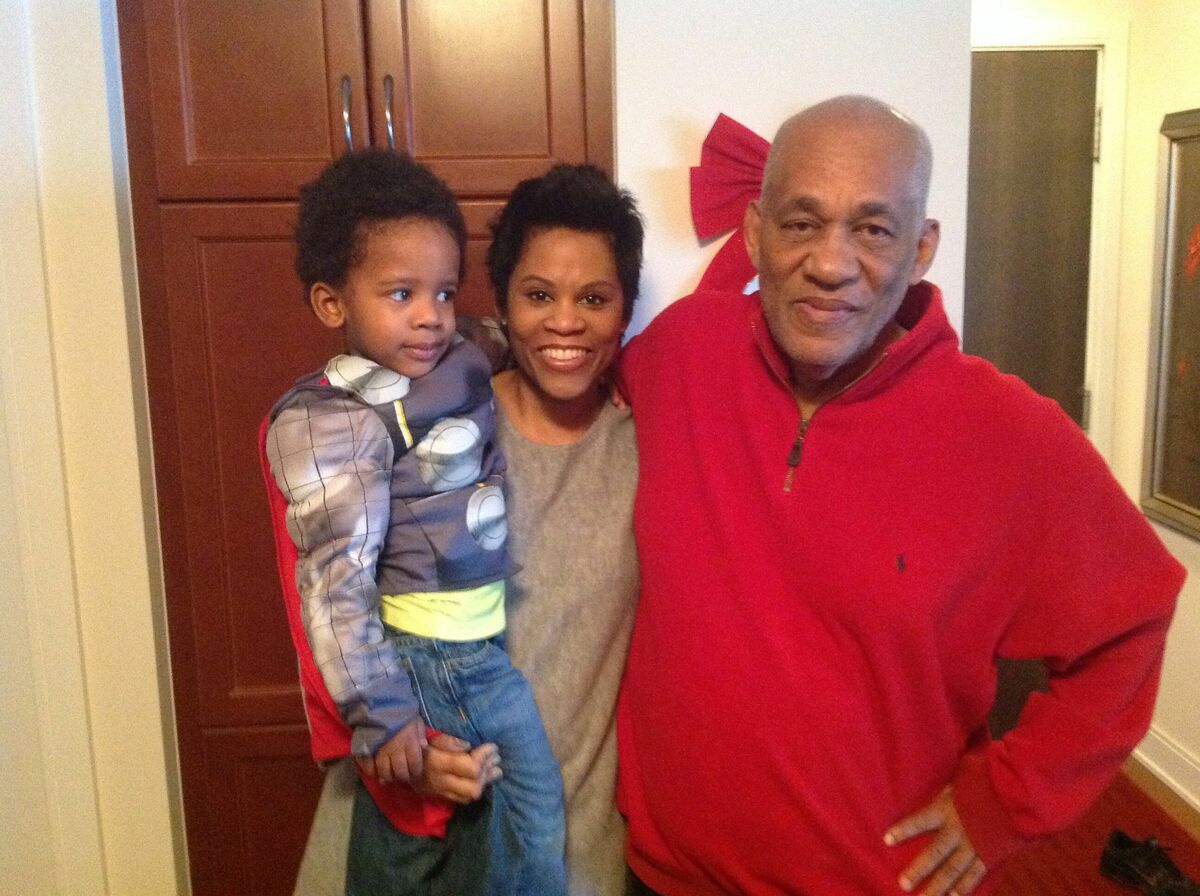

She says part of what makes her father such a great dad and great educator is his big heart. “He goes above and beyond for people, and they remember him for that,” she says. Marci remembers her dad bringing lunches and bus fares for his students who couldn’t afford it. But she says Joel was a tough teacher who demanded a lot from his students, but had a heart of gold.

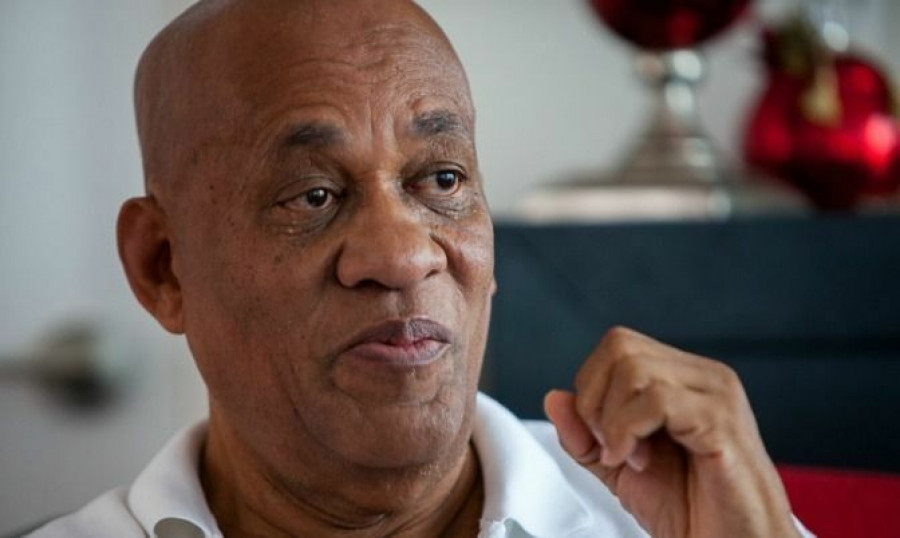

Joel came to Canada from Trinidad 47 years ago to study at the University of Toronto after his parents sold a portion of their land in order to pay for his tuition. Joel graduated from U of T and won a scholarship which allowed him to study at Harvard University in Boston. Joel says that the time he spent at Harvard completely changed his perspective on education and evaluation.

Joel's teaching philosophy revolves around the belief that one must engage a student as a whole person and be invested in their success and well-being. Joel was truly dedicated to his students and says, "My time is the kid's time. Teaching cannot be a 9-3 job. You have to be willing to give and give and give until you can't give anymore."

What was your experience at Harvard like?

Fabulous. The experience was fabulous. That really changed the way I thought about evaluation. At U of T they mark you with a numerical or letter grade, at Harvard they mark you pass or fail. That was a very interesting concept. Pass or fail. Satisfactory or unsatisfactory. And we all studied together in groups, no one competed like at U of T, where we would get books and hide them. That competitive behavior was absent at Harvard because everybody studied together and everybody shared. And that affected how I taught later and how I evaluated kids. And I taught all the teachers at OISE the same thing, I said: "You are all going to be successful, or at least you all assume you're going to be successful. Now let's work together as a group and as a community and you'll all be very successful."

Right from the beginning I kept saying that, and I didn't evaluate the normal way. I'll give you an example: I asked students a question every week and each question was an interview question that they would write an answer to. I would just give check marks. I did that for three weeks; no marks. On the fourth week I put marks. And then there was a buzz in the class, "that's not what we're used to." Then I asked teachers, "what did we learn?" When we as teachers evaluate our students with a red mark, the anxiety level of the class rises. And we debriefed and discussed what putting a mark down can do, and how its effect on students can be negative rather than positive. Some teachers mark in red, and they throw it in front of the class and say, "You got a zero. A big fat zero." That destroys a student.

I know that part of your teaching method involves telling a story to your students on the first day of class, do you mind sharing that story?

I put on the board a name and two numbers, say 1905 dash 1942. And I ask the kids "where do you usually see this?" and they say "on a tombstone." Then I ask "what do you think that dash means?" The dash is the lifetime. All the years that come between the two dates are compressed in a dash. And that has to count, it has to mean something. You have to leave some mark in life. Then the kids analyze the dash in terms of what it can mean: what profession they follow, their dreams.

Why is that an important story to you?

It's significant to me because such a little dash can have such significance. It holds a lifetime; 70, 80 years. And what we have to consider is that we're here for a purpose. You have to find that purpose and don't let people deter us and stop us from where we are trying to get. You have to push forward and you have to progress and that's all part of the dash. One little dash. Leaving a mark, teaching kids, helping kids. That's very important to me. That story had a significant impact on his daughter Marci Ien as well. She named her second child "Dash" in honor of her father and his inspirational parable.

Of all the roles you had (teacher, professor, principal) in which would you say you were able to help kids the most?

As a teacher I could focus directly on the kids because I was working with them. As a principal and vice principal I focused on helping the kids by hiring the best teachers, teachers who care about kids. And you can tell. At first it was hard for me to be a principal because I love teaching kids. So as a principal I always taught. All the staff knew I would cover their classes if they ever had something important or personal to do. That was a good thing because I got to see whether my kids are learning. And because teachers knew I would cover their class and see what was going on they would make sure they're doing good things. So there was a method to my madness.

But for Marci and her siblings, Joel the teacher, was Joel the dad. And she recalls him being dedicated to his kids and their passions. “I did a show called Circle Square, I grew up on the show, I did it from when I was 10 until I was 16. We taped it every Saturday and the call time was 5:30 in the morning. Every Saturday morning for 6 years my dad drove me to the studio, in downtown Toronto and we lived in Scarborough. And there he was a teacher, working five days a week and he got up even earlier on the weekend to take me down there, and he never complained. He brought me to every taping for six years and it was crazy but it was fun. Going on the highway, sometimes we’d have hot chocolate and just the long drives and the conversations on early Saturday mornings were great. My dad has a really big heart and I think that's what made him such a great educator because he cared. He certainly taught me that, and it’s carried on with me. I care for people, especially young people. And his generosity has stayed with me. He also gave us a love of art. And most definitely a love of sports. We've been going to Raptors games for 13 years and it’s a date I do not break,” says Marci.

After you were a teacher and principal you went on to be a professor at OISE, what made you decide to pursue a different career course?

Well I always wanted to go to OSIE. But every time I was ready to go, I got promoted. I thought I was never going to get to teach teachers; I always had a passion for doing that. I wanted to do it so badly I would hook up with OSIE and help them with interviews and help coach the kids with their resumes and interview skills. Because I used to go down to OSIE to volunteer and help, when I retired I got a call from the dean of OSIE: "Joel, we have a job down here at OSIE. We're starting a new course called 'teacher education seminar' it's a broad overall perspective of teacher education. So we'd like you to come down and talk to us." After our conversation he said "you're taking the full-time job."

During your time at OSIE you were the project coordinator of the "at risk to relief program: for at-risk teachers." Why do you think it's important to have training for teachers about at-risk youth?

Unless you have people trained who know what at-risk looks like then they won't be able to teach to correct it. The teachers have to be able to recognize at-risk behaviour, and how to make that child successful. And we never like to say a kid is at-risk themselves. When we say that a kid is at-risk we really put a stigma on that kid. Every kid can learn, it's just that they don't learn at the same rate every day. They can all learn and they all will learn if the teacher wants them to learn.

One of the interesting points of the program is that it focused on "a holistic approach to those at-risk" would you be able to explain what that approach is?

We focus on the whole kid. We make sure that student ate because that's basic and if kids are hungry they don't want to hear anything about math. So we take care of that. Then we look at home; does that student have a place to study? Then we talk to the parents; we ask them to set aside a spot where their child can sit and do homework and we ask them to encourage their child. Not everyone has parents who help them succeed so we try and fill in and be good teachers. That's why we don't just work 9-3. Then we look at the academics. I told them "I'm here to help you succeed and we're all going to succeed, but here’s the deal" then I lay out what they have to do, like spend half an hour studying at home every night. "And when you go home I want you to teach your parents what you learned at the dinner table." And every night the parents had to be involved; you have to involve the parents in the child’s education.

Another thing that was implemented into the teachers’ at-risk program was professional seminars where teachers could create and discuss teaching methods with each other. How important do think those seminars are to have in any job setting?

Oh it's very important, to have that collegiality and an environment where everyone is willing to share, like I described at Harvard. Teachers sharing expertise, kids telling teachers "this is what you can do better for me." It's very important that teachers do that and also that they do that with their students. We have to be able to look at ourselves and we have to not be afraid to do something about what we see. Self-awareness and making adjustments, not just looking at ourselves and saying "I'm pretty good."

Some teachers say there's a difference between wisdom and knowledge, what do you think those differences are?

With knowledge you can pick up a book and read it, then you have knowledge of that book. I think wisdom goes deeper than knowledge. Anyone can get knowledge. When you become wise you are able to evaluate, appraise, assess and learn from your knowledge. When you become wise you seek knowledge.

Is there anything you think you can do as a teacher to instill wisdom into students?

Yes, by helping them when they get knowledge, encouraging them not to stop there. Tell them "I want you to go home and think about this and think about how you can apply this to your life. In what you do, how you treat others. Then tomorrow in class we'll discuss it." From that you will gain wisdom. Wisdom is one step further than knowledge.

By

By