It's a rollercoaster ride that many Caribbean descendants can relate to.

Playwright and screenwriter Andrea Scott is a Jamaican descendant who meshes together a scenario that tackles all the nuances of a Jamaican household in her new play, Get That Hope, showing now at the Stratford Festival. Directed by thespian, writer and director André Sills in his directorial debut at the Stratford Festival, the play takes place in a place familiar to many Caribbean folks—the historical Little Jamaica in Toronto.

The play’s synopsis introduces us to the Whyte family, which is loosely based on Scotts’ real family. Ginger beer is cooling, and rice is soaking, ready to celebrate Jamaican Independence Day on a sweltering hot day. However, the family squabbling and other Caribbean-isms threaten to ruin the special day Richard Whyte had in mind.

Many have been privy to this type of event and its outcomes, but the dynamic is perhaps one that’s hardly depicted on stage. While Scott was in Stratford as a mentee, she saw Long Day’s Journey Into Night by Eugene O’Neil and the essence of Get That Hope was born. She decided it was something she had to bring to the forefront of Canadian theatre, especially at Stratford Festival, so the Caribbean diaspora could be represented on a big stage.

“As I was sitting in the audience watching the play, I remember thinking, ‘Why don't we as Black Canadians have anything like this?’ I mean, Long Day's Journey Into Night is set in, I think, 18 hours of an Irish American family, and they are dysfunctional and they love each other but they're fighting. It's a much grimmer perspective of what it was like to live in 1912 as an Irish family that's kind of upper middle class.”

“So, I took this play but transposed it to a West Indian family at Oakwood and Eglinton in present-day Toronto. Also, it's Jamaica's Independence Day. Basically, any West Indian family would be able to say, ‘Oh yeah, I know that dad, oh yeah, I know that mom, oh that's me, the long-suffering daughter, and her wayward brother who gets away with everything but does nothing, and she gets put upon for the whole time.’ …We've had enough trauma; trauma porn on stage and in theatre, so let's do something that shows the joy in the light, while also showing the frustrations of our family that I thought people would really relate to,” says Scott.

With the same notion that we can be dysfunctional and continue to love each other, director André Sills was fascinated with another perspective of the play: how we perceive each other. “[It comes down to] heroes and villains—how quickly we want to do that to people and even our family members and make them heroes and villains. I think it’s easier to do that, than to actually see the human that your mother may be, or the human your father may be. You know, we have so many expectations and pressures put on us from our parents or hopes and dreams that we put on our parents as well. [But] when is the moment you finally see your mom and your dad as a human, as opposed to the context of them being your parental entity?” says Sills.

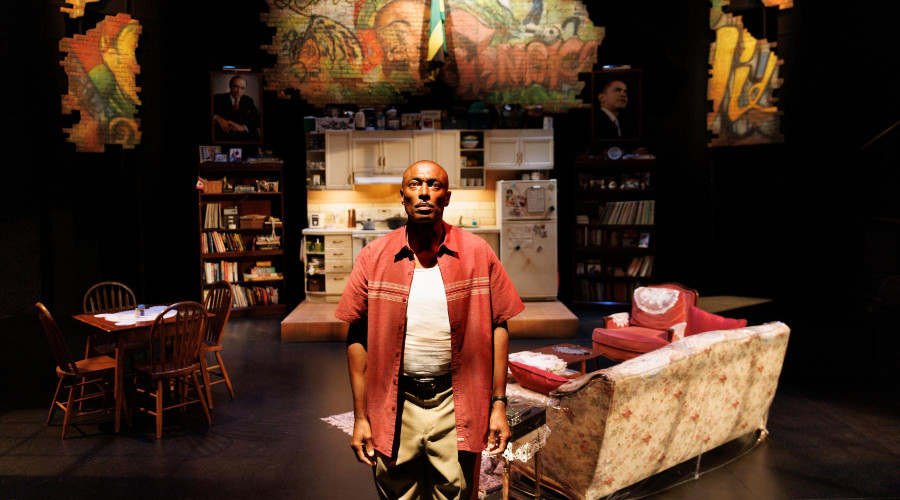

From left: Jennifer Villaverde as Millicent Flores, Savion Roach as Simeon Whyte, Conrad Coates as Richard Whyte, Celia Aloma as Rachel Whyte and Kim Roberts as Margaret Whyte in Get That Hope, Stratford Festival 2024. Photo: David Hou

No doubt that there is also the underlying theme and dynamic of struggle. ”I'm talking about the gentrification of the neighbourhood and things being torn apart—at the same time too. We're seeing this family struggle in a lot of ways with either finding work or within their dynamics between each other. One of the things about family too, is that it's one place that you know, or unintentionally know, you can behave your worst. And, for the most part, be okay with it.”

While the Caribbean isn’t a monolith, there are certainly shared experiences. Many will understand the exploration of undiscussed elements like the relationship between patriarchs and infidelity, the expectations of kids in a Caribbean household, how parents communicate with their kids, the adjustment for step-children to be transported from ‘back home’ to live in a foreign country, and the collective trauma of mothers and daughters in Caribbean families never being appreciated, but always doing the most.

When you sit down and peel back the layers, we’re a complex set with many intricacies. Even Scott recalls reading about the collective desire to create an all-Black production of Long Day’s Journey Into The Night around 1967; however, critics had harsh words.

“One critic in particular said, ‘Black people can't understand the complexity of emotions and stress and trauma that we do.’ I was like, are you kidding me? That's why I said I wanted to see an all-Black production of Long Day's Journey into Night. I want our stories told originally from our experiences. I want everyone to see the similarities in family and that we were all lied to with TV people getting along and everyone loving each other, with mom baking cookies and dad sitting on your bed and like, ‘What's up, Champ? Are you okay?’ Guess what? That is not real. We still have joy and love for one another, even if we're fighting. Sometimes people are very careless with their words, but it doesn't necessarily mean that they don't love you, respect you or want you in their life,” says Scott.

“I think more often than not, that's the biggest struggle most of the time—to let people see us as humans,” Sills says. “And in a lot of ways we have the same struggles, maybe some different struggles, but I don't know. It's a funny thing because I think, unintentionally, people want to other us. They just need a reminder sometimes to see that our struggles are their struggles too.”

Ideally, Scott says she would love for Caribbean attendees to walk away from the play and see their reflections on stage. She would like characters to remind everyone of their beloved family members and come away with a little more verve and understanding than they did when they entered the theatre. “I hope people walk away and be like, ‘Didn't Rachel remind you of Aunt Pat?’ Or, ‘Didn't Richard remind you of Uncle Teddy?’ and laugh about it. I want people to be dancing when they leave because I want the soul and rhythm of our language, music and tragedies to live in their souls as they walk out onto Dowdy Street.”

Get That Hope runs until September 28 at the Studio Theatre. Tickets are available at stratfordfestival.ca or by calling 1.800.567.1600.

By

By