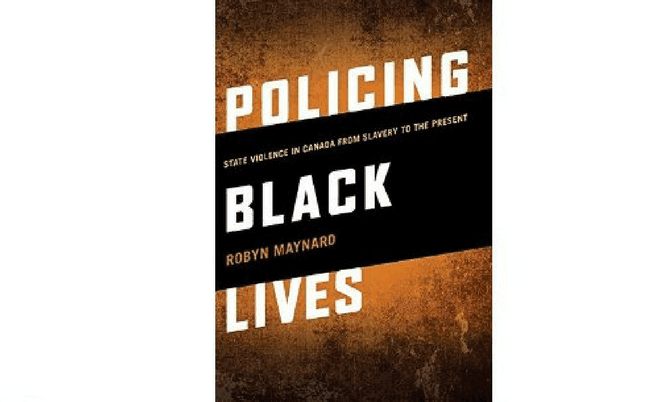

In her first book, Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to Present, described by political activist Angela Davis as “meticulously-researched and compelling,” Maynard gives one of the first comprehensive accounts of 400 hundred years of state-sanctioned violence against Black people, challenging Canadian narratives of liberal multiculturalism.

When most people think of the policing of Black lives numerous African American examples come to mind, from Rodney King to Philando Castile, and the dozens other unarmed Black men and women shot or beaten to death at the hands of police. Maynard’s book is an eye-opening reminder that Canada, too, has a long history of policing Black lives.

Maynard draws historical connections between Canadian slavery and the criminalization and surveillance of Black bodies beginning in the 17th century in New France (present-day Quebec) through to the contemporary realities of those who have died at the hands of police, such as Jermaine Carby, shot dead by Peel Regional Police in Brampton in 2014; Andrew Loku, shot to death by Toronto police a year later; and most recently, Bony Jean-Pierre, shot and killed by Montreal police in 2016.

Policing Black Lives raises important questions not only about anti-Black racism deeply embedded within Canadian institutions but also the ways in which these same institutions, from the government through to the media, often displace these issues as not belonging to the nation.

In response to questions about the death of Abdirahman Abdi, for example, a 37-year-old Somali-Canadian who succumbed to injuries he sustained when he was beaten by Ottawa police last year, Matt Skof, president of the Ottawa Police Association said in an interview with CBC, it was “inappropriate” to discuss racism with regard to his death.

When I spoke to Maynard in Toronto earlier this month, it was abundantly clear that the issues facing Black lives in Canada are not American imports; they are deeply rooted in Canadian slavery and anti-Black practices and policies. Policing Black Lives is sure to become the reading companion to #BlackLivesMatter.

Cheryl Thompson: I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that tries to attest to some of the things that you talk about from a Canadian point of view. Most of the time in North America when we talk about Black lives and policing we defer to the American context. Tell me why you wanted to write this book, at this moment?

Robyn Maynard: I have spent the last decade of my life doing very engaged community work … a lot of it with black teenagers. When I was 19-years-old I moved to Montreal and I was working doing outreach work with an NGO with youth in group homes. These were youth who were criminalized, and youth who were close to the street. What I noticed early on was that so many of those youth were Black.

CT: One reoccurring theme throughout the book was the need to remember the roots of state-sanctioned violence against Black people as being rooted in slavery. People in Canada, especially, do not usually make this link. Why was it important for you to do so?

RM: People still don’t even know that we had slavery…. I’m really trying to argue, and I think it is more accurate to argue, that the way the Canadian state treated Black people then is how they treat Black people today; the patterns of behaviour have been very continuous. There are so many continuities from then to now and so it was really important for me to not overlook that because in so doing, it lets the government off for something that is too often seen as … a diversity problem that began in the 1960s but in reality, this is something that [Canadian governments] have been managing in a very violent way since the 17th century.

CT: One of the reasons you say you felt compelled to write this book is because anti-Blackness, particularly anti-Blackness at the hands of the state is wildly ignored by most Canadians. Why do you say this? Do you think it is ignored or is it not thought about at all?

RM: I think it’s both. I use the word ignored specifically because I do think there is a difference between a lack of representation and erasure. If you look at the work over the last 100 years that Black communities have been doing very publicly. and there have been brilliant Black historians that have been documenting anti-Black racism that information is out there, you can’t really say that it’s something that people aren’t thinking about.

At a certain point, we need to look at what becomes willful ignorance and willful erasure. Yes, people are not exposed to this information but there is also something that is being repressed. The realities of Black people in Canada has even been called out by the United Nations at various times over the decades. This is not something, for example, the federal government has not heard of. They have not made any public statements about the crisis of racial profiling or Black incarceration and these are things that we know and that we have known for a long time.

CT: In the Introduction to the book you state that Black communities experience significant societal pressure to appeal to “white middle-class norms” and to defend our communities on the pretext that we, too, are “upstanding, law-abiding and virtuous citizens.” I found this really interesting because I think especially in Caribbean communities in Canada respectability politics are very real and there is often a generational divide where I feel that certain generations don’t always understand what appealing to these kinds of norms mean for many Black youth. Would you agree with that?

RM: I really understand where that comes from especially if you’re coming to a new country and don’t have that generational knowledge of how racism here has continued to perpetuate itself so it’s like the state gives this promise that if you don’t break the law and if you go on to university, somehow racism won’t happen to you. But, often, what the second generation learns is that no matter what happens you’re still more likely to get kicked out of school, you’re still more likely to go to prison if you’re smoking weed with five white teenagers, so I think what we have to realize and it’s really important for me to focus on saying for example that we’re not criminals because the state has invested so much in representing Black people as criminals and over-policing, which then is always going to result in over-incarcerations.

What we really need is to challenge the criminalization of Black bodies itself and to actually defend the lives of people who have not only been “good” and unjustly criminalized … but also for people who have broken laws, which a significant portion of Canadians also have. Instead of getting into that trap that tells us if we jump through certain hoops then we will be accepted we need to realize that that has never happened and that’s not going to happen and we need to start to change the train of struggle.

CT: One of the things you also touched on in the book is the link between neoliberalism, shifts in capital, and race. I wonder what your thoughts are on how these things connect because I think they do connect but people don’t often make the connection between the way Black bodies are surveilled and capitalism.

RM: Absolutely. A lot of people were like, why do you have a chapter on Black poverty in a book that’s about policing Black lives? To me, that’s been another part of the surveillance and control of Black people’s lives – systematically excluding them from access to wealth, from well-paying jobs …. I think we also need to think about the way that we are monitoring and excluding Black people, it’s something that stems from slavery but it’s just as much a way of controlling Black people other than policing them in the streets, such as having people not have access to gainful employment to be able to feed their families properly. These are the things that actually have an impact on our ability to live healthy lives.

CT: Another topic you touch upon in the book is the issues of a lack of empathy. That is, a lot of the shootings of unarmed Black people have to do with a lack of empathy toward Black bodies. Would you agree?

RM: Yes. I think it really stems back to the pathologization of Black people that took place under slavery that still exists today on a global scale. I think that is what connects the fact that there is very little sympathy for example for Somali refugees who were subject to heavy criminalization as soon as they arrived in Canada.

It’s not only a lack of empathy but there is actually a fear, a very specific fear and pathologization of violence, of danger, and of a lack of intelligence and these were really representations of blackness that were created centuries ago but still have enormous impact on our immigration and resettlement policies and also on the ways that police are looking at our communities. It is not a coincidence that Somali communities that have come here are subject to really intensive policing and the death of Abdirahman Abdi is only the most recent example of that.

CT: In my assessment, one of the other areas we simply do not pay enough attention to in Canada is the entanglement of race and space.

RM: Absolutely. I talk a little bit about public space … [such as] environmental racism and the placement of dumps in Nova Scotia and how that happens like Africville but also even now dumps are placed almost exclusively next to mostly Black and Indigenous communities. Even if you look at Montreal, which communities have access to decent public transit and community health services, and if you look at St. Michel and Montreal Nord there’s barely anything it is so difficult to access those spaces.

CT: Those communities are completely cut off, it’s prohibitive to people coming and going.

RM: Yes, and people have difficulties accessing health services or even transport so even that is racially distributed. That, too, is something that we really don’t pay enough attention to in a Canadian context because it sounds like an American issue.

CT: In Toronto, as you’ve pointed out, there were so many police shootings of unarmed Black people in the 1980s and 1990s and so much Black activism, and yet, when you hear of a shooting today, our media never go back to that time. They never create a timeline of police violence against Black people in Canada.

RM: Right? They will not give our timeline they won’t say, “We’ve been killing Black people in Canada since at least the late 1970s.”

CT: There is complete erasure. If you’re a young person today your perspective is very skewed because you’re thinking, why are they making such a big deal, it was just one shooting meanwhile you don’t realize that this is 40-plus years of consistent state violence against unarmed Black people, not just one shooting.

RM: Black communities have never been silent about this, you can’t blame Black communities we have always been in the streets about this.

CT: And yet, it’s like it never happened. There is such a silencing.

RM: And I think that is one of the most horrific elements of what we call the “liberal, multicultural white population.” It’s the ability to overlook and actively erase systematic forms of Black suffering and Black death that have been happening under the guise of multiculturalism.

CT: Do you think that the Africentric School is a model that we need to see rolled out in more communities across the country? People think an Africentric school is just for Black students but it’s a form of pedagogy, of teaching from an Africentric perspective. Do you think that is the right step toward shifting the narrative?

RM: I think it is one important step and one that Black families and Black educators have been asking for in different cities for a generation so I think it’s really worth looking at that. I think the Black Lives Matter Freedom School is another beautiful model of teaching Black youth not only about Black contributions to history and also of the realities for Black queer and Black trans people and the contributions of all these different Black liberation movements…. I also just think we do need to look at the curriculum in the education system in Canadian public schools. In Quebec, for example, blackness is almost entirely absent.

CT: What do you hope people take away from this book?

RM: I have been really happy with the reception it has received. It was amazing that Angela Davis wrote me a blurb for it, and I have received some really positive feedback so far that has been really encouraging, and I put so much of my heart and my life into it so it means so much to me. I wanted it to be written in a really accessible way so that the material in the book will become more widely known.

This is just another attempt, like the generations before me, to interrupt that silencing. I’m not trying to be like, “Everyone needs to read my book,” but the information that’s in this book needs to be publicly known and people need to understand the history of policing Black lives from slavery to the present if we are going to be able to effectively address social injustice and anti-Black racism in Canada. For me, that’s why I wrote the book, and that’s what I hope it can help to accomplish along with other things.

By

By