Plaques commemorating the community’s citizens are bountiful in the area, particularly of one notable Black woman, Mary Ann Shadd.

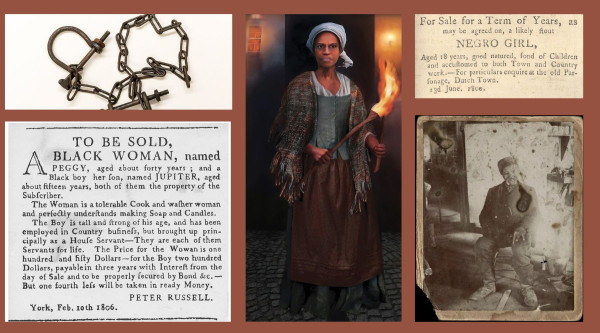

Shadd was Canada’s first Black female news publisher. The abolitionist journalist held an important space in Canadian history advocating for Black people’s and women’s rights during a time of slavery.

“She was so outstanding and unique for her time,” said Adrienne Shadd, a Toronto-based researcher and great-great grandniece to the journalist. “She wasn't afraid to voice her opinion as a woman.”

Mary Ann Shadd started the Black newspaper, the Provincial Freeman, in Windsor, Ont. in March 1853, eventually moving to Toronto and finally Chatham, Ont. where it stayed until 1857. Around one-third of Chatham was populated with Black people at the time — among one of the largest Black populations settled in Canada West.

According to Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society (CKBHS) executive director-curator Samantha Meredith, Shadd promoted this thriving community in her paper as a free space for escaped Black slaves and to help other communities’ freedom efforts.

The newspaper was published on a weekly basis and used to promote emigration to Canada by publicizing the successes of Black persons in the country. Mary Ann Shadd promoted women’s and marginalized individuals’ rights and featured prominent anti-slavery authors.

“They [the Black community] were also very supportive of Indigenous peoples who were suffering similar battles for freedom,” she said.

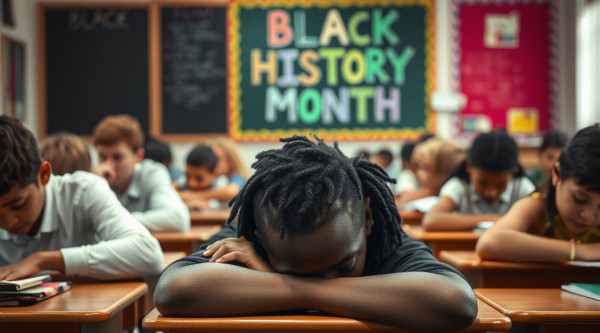

Telling the tale of history through education

While there are monuments symbolizing the community’s history, CKBHS president Dorothy Wright-Wallace said the museum is working on making their legacy known through education.

“I wish we had knowledge of this history growing up, someone we could have looked up to,” said Wright-Wallace. “We need our heroes too.”

The 77-year-old resident was born and raised in Chatham, bearing witness to the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s inspiring her to bring the legacy of Shadd and other notable figures in the area to schools.

She works with Meredith, who organizes walking tours for students to learn more about the area’s rich history. Meredith, who is white, says that growing up, she never learned anything about Black Canadian history either.

With the advent of the Black Lives Matter movement reaching greater prominence over the summer, Meredith said the museum has been increasingly working with teachers to incorporate Black Canadian education in their curriculums.

Not only are Chatham’s students and residents educated on the place’s history, but historians at the museums nearby are compiling archives and collaboratively mapping the genealogy of notable figures to track their descendants, many of whom live in Chatham and are unaware of their ancestors’ achievements.

It was at the Buxton Museum that Adrienne Shadd first discovered she was the great-great grandniece to Mary Ann Shadd after strolling in one day as a teen. This discovery led her to pursue a career in finding the achievements of other historical Black Canadians.

“I figured that if my family had these kinds of ancestors that had done such amazing things, it made me wonder what other stories out there we could find that were equally as amazing,” she said.

Mary Ann Shadd was also a lawyer, activist and teacher in the Chatham community and established a desegregated school in Windsor, Ont.— albeit no white children actually attended the school. According to Adrienne Shadd, a quarrel with Voice of the Fugitive publishers Henry and Mary Bibb led to losing funding for the school, but further galvanized Shadd to start her own paper.

“The newspaper for historians is a fantastic resource,” she continued. “It talks so much about what was going on in Chatham, in Canada and in the U.S. for Black people. It’s an incredible window on the happenings at the time.”

The Bibbs were proponents of the segregation system. Around 1852, Mary Ann Shadd engaged in a heated argument with the couple which ultimately became public as the three of them wrote numerous editorials about each other in the Voice of the Fugitive. This resulted in Shadd losing funding for her school.

Shadd first started publishing under the name of men who were on her masthead including Samuel Ringgold Ward, a Black abolitionist and even under her brother Isaac’s name. But with time, she replaced it with her own.

True to the nature of the community Mary Ann Shadd lived in, Wright-Wallace said Chatham’s residents during the 1800s built similar desegregated schools, hotels, stores and churches to ensure escaped Black slaves felt safe.

Shadd’s work at the newspaper gave Black women an opportunity to highlight their experiences and gave the residents hope for a better future. She was supported by numerous notable historical figures, including American abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

But according to Adrienne Shadd, if her great-great-great aunt was alive today, she would be shocked to hear Black men and women face the same discrimination as they did then, especially in the mainstream media.

“But they [the media] can be really important in giving expression to Black people's desire for freedom, for equality. Give more Black people some of these on-air spaces... so that we can be the voice to express our own concerns,” she said.

For now, historians such as Shadd, Meredith and Wright-Wallace continue educating younger generations on Chatham’s great historical figures and history.

“We need to start with the younger generations and not only tell Mary Ann Shadd’s story, but tell the stories of all the people that lived here and let the next generation understand who their ancestors were,” Wright-Wallace said. “Because a lot of kids in this neighborhood really don't know where they come from.”

By

By