The public outcry that followed Floyd’s death included protests and calls to abolish the police that has led to a “racial reckoning” around the world. More people are critically discussing the intersections between race, the public and the police.

Toronto City council rejected a motion to cut the Toronto Police Service’s (TPS) budget but it approved a motion calling for a suite of reforms. A report on police reform by the Toronto Police Services Board resulted in 81 recommendations, including the creation of an educational campaign. TPS and the Police and Community Engagement Review (PACER 2.0) Committee collaborated to launch the Know Your Rights (KYR) campaign in March. Through an educational video and social media content, the program’s objective is to inform the public about their legal rights and the responsibilities of police officers during encounters.

“The KYR campaign was created to support better outcomes in any interaction with the community and police. In particular, with Black, Indigenous and racialized people,” explained Kelly Skinner, a Black woman and TPS Inspector with over 20 years of experience.

She says another goal of the campaign is to take a step towards mending the relationship between the police and racialized communities. According to the CBC, between 2000-2017, 37 percent of victims in fatal encounters with the police were Black, despite representing just over 8 percent of the population. Skinner believes that the practice of carding, which was banned in Ontario in 2017, also contributed to the fraught relationship between the police and racialized people, particularly when it came to youth. Carding disproportionately affected Black and Indigenous people.

The KYR campaign is meant to demystify Regulation 58/16, the street check regulation. Under this regulation, your participation is voluntary, and police are prohibited from arbitrarily collecting your identifying information. If an officer asks for identifying information (such as your name, address, or age), the officer has a duty to inform you that you’re not required to provide any identifying information, tell you why they’re attempting to collect that information, offer an on the spot receipt of the interaction containing the officer’s name, badge, division, date, time, location and reason for questioning, and uphold your right to leave.

Skinner says the campaign will benefit both police officers and the public. “It's also a great reminder of our unconscious bias training and ensuring that all of our interactions with members of the public are done without bias.”

Yvette Blackburn is the Canadian Representative for the Global Jamaica Diaspora Council and has been involved with PACER since 2012. Part of Blackburn’s role includes reaching out to members of the communities to find out their perspectives on policing.

“The standard thread is that there’s over-policing, discriminatory practices, the [unequal] levelling of charges, how they are spoken to, the tickets, and the abuse [both physical and of power],” Blackburn detailed.

“The biggest theme was probably the lack of trust in BIPOC communities, which the police have to work to improve and KYR is a part of it,” Skinner added.

According to Blackburn, one of the benefits of the campaign is that it empowers citizens with tools to identify a problem and file a report.

“I’d feel good in understanding that if an officer was foolish enough to breach my rights, that there would be accountability that they would not have been experiencing before,” she said.

While Blackburn is somewhat skeptical of the police force’s motivations, she believes that the combination of the campaign informing the general public, and internal mechanisms to hold officers accountable that discipline those who go rogue will curb bad behaviour.

Blackburn also noted the need for a paradigm shift when it comes to policing that isn’t so combative and adversarial. She and Skinner agree that until this is addressed, we will continue to see the same problems.

“Policing has moved from ‘To serve and protect’ to a more militarized framework of dominance and control of the citizenry that they have to serve. I think part of the issue is that the lines were blurred and officers have stepped too far over it to hinder the rights of citizens,” Blackburn stated, “and when we talk about the use of force, the extra equipment, and the anti-Black racism that's also steeped in the historical framework of who officers are and how they police, etc.” The mention of police shouldn’t come with a negative connotation and the sight of officers shouldn’t fill law-abiding citizens with fear, says Blackburn.

As a Black police officer, it’s been a challenging and emotional year for Skinner but it was a catalyst that led her to join PACER 2.0. She said that people like her have a responsibility to try to make things better. At times, she finds the critiques of her profession hard to hear but she understands where they’re coming from and wants to be a part of the conversation.

“I wouldn't expect anyone from the Black community to get up and make excuses for every Black person who’s committing a crime. I also would not stand up as a police officer and make excuses for every police officer who is neglectful, racist or profiling,” Skinner explained.

Skinner believes these difficult conversations are necessary because we have to work together to find solutions. But others argue that the only real solution is to abolish the police.

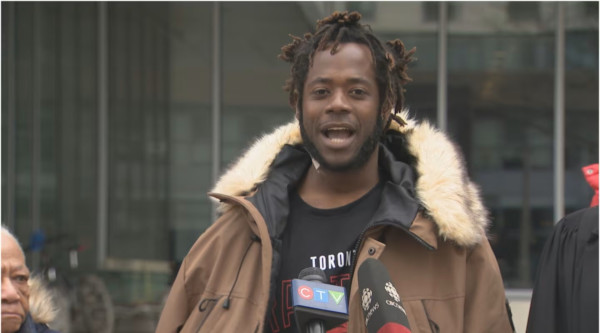

Rinaldo Walcott is a Professor of Women and Gender Studies Institute at the University of Toronto. He’s also the author of On Property, a book that looks at the connection between slavery, property and policing. In the book, Walcott calls for an abolition of property that ties into his thesis calling for the abolition of the police. Walcott doesn’t believe the KYR campaign can help mend the strained relationship between racialized people and the police nor does it address the real problem.

“There's a massive gap between what is written into law, what are police duties, and what police actually do when they encounter people,” Walcott explained.

He cited the recent verdict involving two police officers and the Neptune Four as evidence. Police officers Const. Adam Lourenco and Const. Sharnil Pais were found guilty of unlawful arrest after accosting four Black teenagers in 2011. According to one of the complainants, Lourenco physically and verbally assaulted him, and when his friends rushed to his defence, Pais drew his gun. The encounter ended with the four teens being arrested, charged, and strip-searched. Ultimately, the charges were withdrawn.

In the victim impact statement given in March, one of the victims said that he felt criminalized and that he no longer trusts the police. However, the most damning detail may be that he admitted that he no longer relies “on his rights when interacting with police."

The two officers were suspended and docked pay for a combined 15 days for their misconduct. For Walcott, this encapsulates everything that’s wrong with PACER and the campaign.

“Those four young men knew their rights, told the police that they knew their rights and what happened? It's taken a decade for this case to be resolved and for the police officers who were involved to receive some kind of punishment.”

Walcott said that even with the KYR campaign in place, police hold all the power during interactions and that they will always say that they had a reason to stop someone. In his own experience, he’s found that officers become arrogant and authoritative when people show that they know their rights.

“In fact, they become offended by it and then want to show that they're the ones in authority,” Walcott explained.

Walcott believes that civic education and knowing one’s rights are important but says that it doesn’t guarantee one’s protection.

“People should not be lulled, especially Black people, into the romance that because you know your rights the police are not going to abuse you. That is the kind of dangerous fiction that will get Black people killed,” he said.

"Policing ultimately fails because more often than not, police are responding to violence rather than actually preventing it, and because police respond to violence with violence, it creates a cycle," Walcott argues. He acknowledges that policing has been around for centuries and the “logic that makes policing appear legitimate has been so deeply implanted in us individually and collectively.” He and other abolitionists argue that we need long-term action, planning and the establishment of “mechanisms that can allow us to ease ourselves off of policing, as a way to solve conflicts in our society.”

Some of the things Walcott believes we should do in the interim are create a society where BIPOC are not prejudicially profiled, the disarming of police, and the reallocation of police department’s budgets. “These changes would result in a paradigm shift,” Walcott says, “and then change our perspective on what it means to deal with conflicts, emergencies, and what it means to care for each other.”

Both Skinner and Blackburn said they’d be in favour of reallocating some of the police’s funding and responsibilities, as well as directing them to agencies and organizations better equipped to deal with certain situations. However, they don’t support the idea of abolishing the police outright.

“We have to do this together because we can't do it alone, and we can't walk away and completely defund the police because I don't think that the community can do it on its own either,” Skinner urged. “I know people are hurt and there's distrust there, but we have to find a way around it and find our way above it so we can work together to improve and do better.”

Blackburn took it a step further and called the idea to abolish the police “ridiculous.”

“To say that we need to abolish the police, that’s not going to fix our situation. The best solution is to build the frameworks that are there,” Blackburn said defiantly.

She and Skinner also rejected the critique that measures like more diversity in police forces, and more training on topics like white privilege, use of force and interacting with marginalized communities have no effect. Blackburn says critics and marginalized groups need to be at the table in order to track “the trajectory of change.”

“Growth is not going to happen unless we're at the table together. We need people working internally and externally who are allies and have the same kind of goal," Skinner added. “I think if we're going to move forward, we need more community buy-in and understanding.”

With a radical restructuring of the policing system at the heart of his calls to abolish the police, Walcott believes that since we made the current policing system, we can make a different one.

“We have to engage in a serious process of downsizing the police so that by the time we are ready to abolish the police, the police will be such a small entity that abolishing it would be actually meaningless.”

Time will tell which strategy offers more safety for communities most affected by the challenge of how best to police the police, in a climate where many from those communities are questioning whether they even need them at all.

By

By